In this most trying of years, we looked to those in the film community who went to great lengths to bring joy to audiences and a reason to be optimistic for the future for Our Favorites series. We will be highlighting their efforts throughout this week.

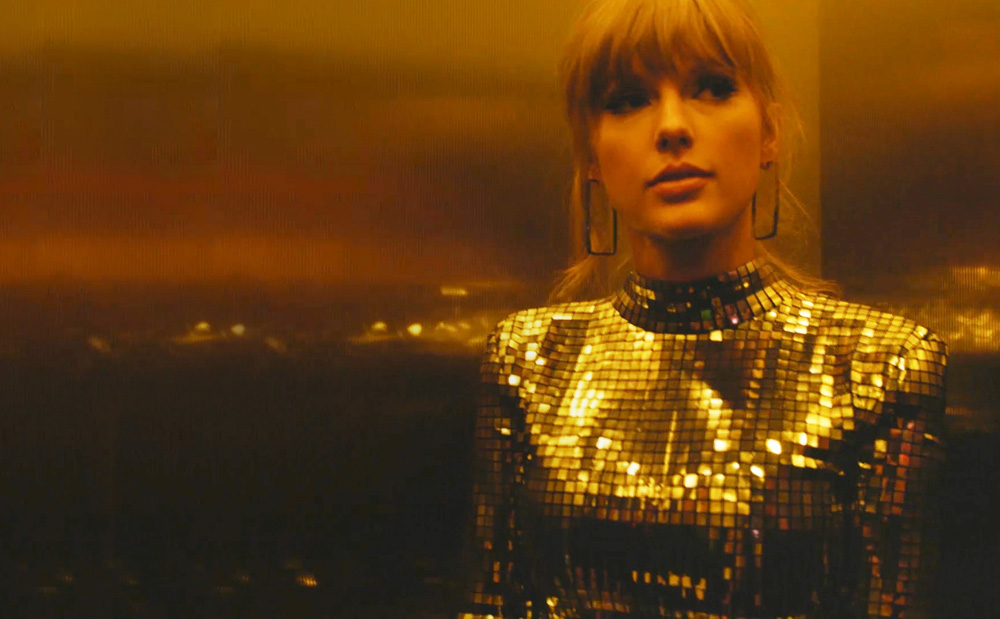

A lot of our favorite moments in 2020 involved Taylor Swift, but the one that was committed to film — the most delightful and awe-inspiring scene of any in the medium this particular year — occurs 46 minutes into “Miss Americana” when the singer/songwriter is wrapping up recording her duet “Me!” with Panic at the Disco’s Brendon Urie. It starts out innocently enough when Swift expresses her excitement that Urie take the additional time out to join her for the music video, and not one to ever let practicality get in the way of a cheerful notion, she starts thinking out loud about what her plans are, describing an entire storyline that involves a fight in an apartment leading to a parade in the streets that ends with her riding a unicorn.

“Taylor Swift has a dream about something that she sees one day and then it can be immediately realized in this massive way,” says the film’s director Lana Wilson, who credits Greg O’Toole, one of “Miss Americana”’s dream team of editors, for mashing up the footage shot months apart. “And that’s what I loved about it. How inspiring is that to witness? That she can have these dreams and they’re immediately made a reality because of the level that she’s working at.”

As the exquisite “Miss Americana” wears on, you feel the same is true of Wilson, for whom documentary fans might’ve seen the screaming fans waiting outside the premiere of “Miss Americana” in Park City and could be forgiven for thinking they were there for her as much as for Swift. A phenomenon in her own right, the filmmaker may not have seemed like the obvious choice to follow the artist out of self-imposed seclusion following the release of “Reputation,” Swift’s first since her debut album not to be nominated for multiple Grammy Awards, when her subjects generally live well outside the limelight, previously traveling to Bellevue, Nebraska with co-director Martha Shane for her staggering feature debut “After Tiller,” to show the toll it takes on women to seek out an abortion as access to the procedure is increasingly limited and Nagoya, Japan to profile Ittetsu Nemoto, a suicide prevention counselor who takes on the weight of those who come to him for help in “The Departure.”

However, Wilson delivers a film that is both uniquely — and wonderfully — hers and a gift to everyone else, a rousing tale of empowerment where Swift faces the same insidious and abstract feelings of fear and inadequacy the director has explored so insightfully before and rises above the battles that she is forced to fight that no male artist likely would, whether it’s recognizing and attempting to push past the limits of the image that’s been cultivated for her to appeal to the masses or dealing with a civil suit from a deejay upset she called him out on his groping during a photo opp. You can tell Wilson knows her subject intimately when she prefers deep cuts to the hits from Swift’s extensive catalog to help tell the story — and more impressively, using it sparingly, and a stroke of genius among many in “Miss Americana” is the decision to hone in on Swift’s artistic process when she is at her most reflective and unguarded, perhaps a given for most music-related documentaries but hardly assured when Swift had never let cameras into the studio before.

The result is a transcendent experience on par with the magic Swift can conjure from an arena show and in a year where that kind of communal event wasn’t possible, the chance to revisit “Miss Americana” time and again on Netflix could be galvanizing simply to lift spirits or offer inspiration in seeing someone of Swift’s stature still feel inhibited and overcome any trepidation she had about expressing herself when the stakes couldn’t seem greater. After making our favorite film of 2020, Wilson graciously took the time to talk about the making of “Miss Americana” having faith in her own voice on her biggest production to date and the challenge of finding an unexpected angle on one of the most widely covered celebrities of the 21st century.

Did you know this was in your wheelhouse from when the opportunity came up?

I think when most people saw I directed this, it just left people confused, like “Abortion! Suicide! PTSD! What?!?” When I got a call about this film, it’s actually when I was finishing “A Cure for Fear” and and I just immediately thought, “Yes.” So I guess I did think it was in my wheelhouse. I was also a fan of Taylor’s albums and I had a little sense of who she was as a person because I knew her songs so well and because I knew her as a songwriter, I thought I could understand this person. Also, because Netflix was calling me and eventually Taylor had watched my films, I thought they want me to bring what I do to this film. Lots of other people could’ve directed this movie. They certainly could’ve decided to work with someone who does more commercial stuff or music documentaries, but they wanted me to do it, so I was like, Okay, I have to bring my style and approach to this.

Well, I think she couldn’t have been luckier. As a fan of you both, one of the exciting things for me was this idea of every time I thought this was going in a direction where I thought I knew everything there was to know, I found out something new. Was it interesting battling expectations in this?

You feel a lot of responsibility when you direct a film like this. I knew immediately more people will watch this movie than any movie I’ve ever made in my life, and you feel a responsibility to the fans certainly, but also to make sure that this is something that people who are not Taylor Swift fans would watch and would be surprised and moved by. Ultimately, I felt the fans are going to love this no matter what and there are a few moments that are specific eyewinks, but largely I just decided to make a movie that would be as universally impactful as possible. What is the story? What are the aspects of who Taylor is and how she is changing and where is she going? What is essential about that? And what is something that almost anyone would be surprised that they could relate to?

That’s what I was always searching for from the beginning [because] with a celebrity of Taylor’s global stature, everyone thinks they know her and they have an opinion, so when audiences are coming to the film with all of these assumptions and preconceptions about someone and a lot of those preconceptions are wrong, you have to be aware of that as a director, but then you kind of immediately tell the audience, “Taylor is not who you think she is. This film is not what you think it’s going to be.” Because it’s the expectation or assumptions about who Taylor is, but it’s also assumptions of what a pop doc is, so you have to confront both of those immediately. The approach I decided to take was to make it this inverted, inside out narrative, so you’ll see a few big moments and turning points in Taylor’s life, but you’ll always hear this interior monologue from her that’s often cutting against what you’re seeing. It’s just a surprising inner voice of what it was like for Taylor in that moment that I thought would be new to even the people that knew her best, her fans.

Was getting to know her any different than other people you’ve filmed with? I imagine it had to be, either because of what idea you might’ve had in advance or the kind of rigorous schedule she has.

It was faster. It was similar in that I always meet my subjects in person with no camera and spend time with them without filming anything first. With some subjects, like in “The Departure,” it was a whole week, but in this case with Taylor, it was several hours. We spent a lot of time together on one day talking through the film and then it was like, “We’re starting! Let’s start next week!” So it was very fast and intense and there is that aspect of it where pre-COVID time she was traveling all around the world, [with] just so much going on at once, so it was a bit like catching a comet and finding chances to film and places to film as much as you can.

Beyond that, one thing that was surprising to me is that Taylor was just as sensitive about having a camera in the room as anyone would be. You might think “Oh, she’s famous, so she’s used to being photographed all the time,” but for her cameras have been a really negative force in her life some times. She has so many images taken of her without her consent and tabloid coverage of her life built to such a fever pitch that it led her to develop an eating disorder. Even press that would be doing a more straightforward interview might be looking for some sort of gotcha moment for clickbait, so what was different with her and I is it took time to build trust and for her to see that if I was in the room with the camera, I wasn’t looking for a headline. I was there to listen, to not judge, to explore, to see who she was and what was going on and to look for stuff that I could relate to in her life and that other people could relate to.

For example, for the first interview that we did, I decided, “Let’s just do this all audio, no camera” because I thought not having a camera there for someone like Taylor Swift would remove this whole level of concern about image and how people will see it. There is so much pressure on her about every detail of the way she looks and any space she might be filmed in is scrutinized in this extreme way, so this first interview was audio only and I think that was a good instinct to have because she was totally relaxed. A lot of the voiceover you hear in the film is actually from that and it was very deep. The part of the film where she talks about the sexual assault trial was from that first audio interview we did and there’s something remarkable just in the way she’s talking and the sound of her voice when she describes that experience and the impact it had on her. I don’t think it would’ve been the same if we’d been filming.

There was something that struck me in one of my favorite scenes in the film — you’re in the car that picks her up from her apartment in New York and you see the throng of fans that’s awaiting her and she has a great line getting in, “This is my front yard.” it’s a great visual gag because as the car starts moving, you come to see there were triple the fans and paparazzi that you thought were there, but I also realized in revisiting it that it doesn’t look like the car’s gotten that far when you’re in a pretty deep conversation about the attention to her weight. Would conversations get pretty intense really fast?

Yeah, it did feel like that and I don’t know if part of that was Taylor’s so fast moving and going in and out of spaces very quickly, but it would often feel like sitting down with her, immediately we’d get into it. There wasn’t a lot of small talk. Talking to Taylor isn’t the kind of interview, whether it’s a formal interview or informal, where it takes a while to get to the deep stuff. It’s all amazing. There was so much rich material and I think it’s because she’s a writer herself. She’s really self-critical and introspective — she can speak really beautifully about her internal state and in a lot of metaphors and imagery.

They’re different mediums, but you’re an artist too, of course. Could that kinship help you figure out the throughline?

Yeah, I remember at the beginning, I wonder if we’ll have anything in common because in some ways, our lives are very different – very different – but I’m also struggling with the creative process and putting your work out into the world and holding it up for people’s judgment and the long-term challenges and ups and downs of a career and what you’re going to do next and what you want to change and what you want to keep the same. All of these questions are a part of every day what you do as an artist and I think that’s the same for everyone. So we had that in common.

We’re also both female artists in male-dominated industries and whenever you’re making a film, your own perspective is always a huge part of what looks to you to be powerful and emotional and funny and real and what doesn’t. So much of that is coming from you as a director, so when I was filming, you notice the stuff you personally respond to the most because you’ve had some personal experience of it before and the same in the edit room with my wonderful team of editors. When Taylor said early on, “I’ve always tried to be a good girl,” it was like feeling like a little lightbulb go off inside me because I felt the same way, and I suspect a lot of other people – especially girls, but not only girls- have also. So you’re always looking for the Venn diagram of where you and your subject overlap. It could be Nemoto in “The Departure,” or someone like Taylor, or an abortion provider like in my first film. You’re always looking for those moments.

Was working with archival material an exciting prospect for you? It seems to become this really great fabric for you to work with in order to illuminate the present tense you usually work in.

Yeah, when we first edited the film, it was almost entirely present tense — the story of this transformational period in Taylor’s life, —and then it was going into the archive and finding what are these moments in Taylor’s life that were psychological turning points for her that led to where she is. I wasn’t trying to make an illustrated Wikipedia entry — you can go read all kinds of things for the exhaustive biographical details about Taylor and I didn’t want it to be a biopic approach because often when I watch a biopic, I feel frustrated that the author of the biopic has not told me why should I care about this unless I’m a fan. So I wanted to open with this question of seeing Taylor through a brief montage of archive from age 12 to the present and hear her in the voiceover say, “I became the person everyone wanted me to be” while she stands on one of the largest stages in the world. Then I wanted the rest of the film to explore the precariousness of that position and to look at Taylor have this reckoning with how she was going to live her life in a new way and moving forward with that.

It was a fast editing process, so we had multiple editors and everyone brought something different to the project. When I look at the film now, I can’t imagine it without any of them. Greg [O’Toole] came up with the idea of [marking time with] age rather than dates or years because it frames the film as a story of a girl growing up to become a woman in the public eye and transforming in all of these different ways. I see Taylor’s conversation with her father and her team towards the end of the film as this real coming-of-age moment where there’s a fork in the road and she makes the decision to go a different path than these people who really love her want her to go. But on this larger level, it is this story about growing up. Towards the end of the film, she says, “Some people say celebrities are frozen in time at the age they become famous, and that’s kind of what happened with me,” so it was this letting go of all these ideas of needing everyone’s approval. That’s something a lot of people struggle with, artists and non-artists, so the age aspect frames from the beginning of the film that this is a story of a girl becoming a woman.

It also allows you to see these infamous events in Taylor’s life differently when you think about how old she is when they’re happening. For instance, the moment when Kanye West takes the microphone from her at the VMAs, that’s a famous moment in pop culture, but does anyone remember that she was 19? It’s easy to look at her and just see the icon and the singer and the brand, but when you think of her as that’s a 19-year-old young woman on stage, remember yourself at age 19 – how would you feel if that happened to you? It helped with this whole inside-out experience I wanted the whole film to have.

Then we could also do some stuff that you can’t do with a lot of people, playing with the texture and the content of the archival material. For example, in that sequence about reinvention, I watched all of Taylor’s concerts back-to-back and in a lot of those performances, especially when she was younger, she’d wear one costume and she rips it off and reveals another. Just for fun, I put those back to back in a timeline and thought, “Maybe one day we’ll use these” and sure enough, one day I had done an interview and one of the editors Lindsay Utz paired bits from this interview of Taylor talking about the specific pressure that’s placed on female artists to reinvent themselves, but only in certain ways that are acceptable to our patriarchal society with this sequence of Taylor ripping off the costumes to reveal endlessly new costumes underneath. She made this kaleidoscopic montage of Taylor’s aesthetic transformations through the years, walking on a tightrope and glittering — telling dangerous narratives, but not too dangerous — and that was one of those moments where having that extensive archive allowed us to visualize a metaphor for the position Taylor was in.

I heard you empowered people around Taylor, and Taylor herself, to film when you couldn’t be there yourself. Obviously, that yields some of the most incredible stuff, not to mention stuff that shows how open Taylor was willing to be, so would you get random video files in your inbox and be blown away by what you would be sent?

Yeah, it was like opening Christmas presents. [laughs] For example, on Grammy nomination day, we couldn’t be in the same room for some reason, so I just asked Taylor to film it herself on her cell phone. That’s a scene that happens pretty early in the film and it’s extraordinary footage, so I would just ask for film and it was always really exciting to look at. And I love the texture of Taylor’s cell phone videos. She’s made a lot of cell phone videos of herself writing songs — in fact, her phone is a really important tool in the songwriting process for her, whether it’s taking notes in the Notes app or doing voice memos of melodies she hears or recording videos of her writing songs so she doesn’t forget stuff as she’s developing it, so she was great about filming things when I couldn’t be there.

But there was a bit of older personal archive stuff that she’d also filmed on her phone that was also fun to look at and use. For instance when the film covers this period that she went into hiding basically for a year after this internet backlash she experienced and she went into hiding, it feels like home movies to me. It’s shot on a cell phone. It’s with her and her boyfriend and it’s when she’s starting to write music for “Reputation” and it has almost the quality of Super 8 film you would take of your family. There’s a special intimacy with that material because it was filmed with Taylor’s own phone and no one else is there.

Has it been a different experience for you putting something out at this scale?

This was completely different. I don’t use social media very much, but I looked on Twitter the day the film came out and it was incredible just to scroll through the hashtag of the film’s name because you see all these comments in all of these different languages. The film was translated into dozens and dozens of different languages and everyone around the world was watching simultaneously, so it was amazing to see responses, especially younger people around the world, saying stuff like “Sometimes I look in the mirror and I hate my body and I hate the way I look but if Taylor could feel that way too and she can get through it than I can too.” Or “sometimes I feel talked down to by men all day every day at my job and I watched ‘Miss Americana’ and I feel inspired to get back out there and stand back up for myself again.” Or people that have wanted to make art but have been afraid to try because they’re afraid of what people will think or will say about them. It was just really rewarding to see all these people from all over being inspired by the film. It could be in either a big way or a small way, but it just meant a lot.

And you got to see it on the big screen again at Rooftop Films in the fall – and Taylor even did an intro. What was that experience like?

It was really cool. It was actually the week in between the election itself and when the election was called, and obviously a lot of the film is around the time of the midterm elections two years ago, so it was fun because I hadn’t watched the film all year and at the drive-in, people can’t applaud. They have to stay inside their cars, but they all honked to show excitement and it was interesting to see when people honked — in this case, there was a moment when Taylor does this political endorsement and says out loud, “A huge number of young people have registered to vote for the first time” and there was wild honking. As we know now, young voters increased by 10 percent this election, so there was that, but there’s also watching the midterms not work out the way Taylor had wanted them to and then going into the studio and channeling those feelings of disappointment into a song called “Only the Young.”

That [song] was actually used by the Biden/Harris campaign, it was one of the final ads of the campaign. It was remarkable to see the lyrics of that song in the context of today. For instance, the lyric “The big bad man with the big bad plans, his hands are stained with red,” in the Biden/Harris ad, that’s with images of Trump taking off his mask after he returned to the White House from having COVID and who would’ve ever expected the context those lyrics could have now? Also just having Taylor talking to herself in a way in the film when she’s at the studio saying, “I’m thinking about all those people who knocked on doors for Stacey Abrams and she still got beat and I want to write a song that gives them hope and inspiration to continue, to keep going and know that this is a long, long path that we’re on, but small incremental change will come.” Now you think about what Stacey Abrams did after losing that election by a hair — how she didn’t sit around feeling sorry for herself, how she immediately went back to work and was so remarkable and effective in what she’s done over the past two years that she managed to turn Georgia blue — there was a lot of honking then too. So it was really amazing to watch it with an audience at this particular moment we’re in.

“Miss Americana” is now streaming on Netflix.