After a long, illustrious career as a cinematographer for nonfiction films – a gig that doesn’t only require a sharp eye but an open heart when capturing people in their most private moments – Kirsten Johnson never felt entirely at home at center stage when she was making the festival rounds with her directorial debut “Cameraperson,” so as her considerable experience in the field dictated, she made an adjustment.

“There was a turning point at Full Frame where they had me up on a stage and like a thousand students were sitting at tables and I was like, ‘This is just wrong.’ I just need to see people at their level, so I came down off the stage and started moving around and I was like, ‘Oh, this is why Phil Donahue does this,’” laughs Johnson of how she ended up turning the Q & As she appears at into genuinely emotional conversations with the audience. “It was so fun to get the close-up and I realized this is my territory as a cameraperson. I can move around and play off of what happens in this space.”

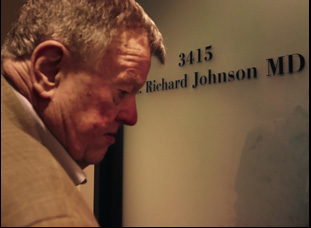

It’s why following the premiere of her latest film “Dick Johnson is Dead,” Johnson would personally bring the mic to an audience member to ask a question and, inevitably, in most cases when the person would invoke the memory of a loved one, ask them for a remembrance of a particularly sweet moment they had with them — after all, they had given her 90 minutes of their time to spend with her father Dick, so this kindness was as fair an exchange as there could be under the constraints of a festival setting. This interaction happens to be indicative of the brilliant way in which Johnson has created a sense of inclusion in deeply personal projects, following up her visual scrapbook of moments throughout her career that made such an indelible impression on her from various productions that took her around the world in “Cameraperson,” with a crafty comedy in “Dick Johnson is Dead” that emerges from a most unexpected place, imagining her father’s demise — over and over again — in order to reduce its impact when he eventually passes.

The filmmaker, realizing she didn’t have much time left with her father, at least in top mental form as he gradually succumbs to the same dementia that stole her mother away from them years earlier, stages a series of outrageous and macabre scenarios in which her dad Dick eagerly participates, spurting red-tinged corn syrup from his neck after being smacked with a two by four or laying on the sidewalk with a breakaway air conditioner is dropped from the sky above. It may be an extreme form of self-care as Dick’s memory can be felt ebbing away as time wears on, but Johnson turns it into the ultimate act of love, marshaling the resources of a massive film production to ensure that her father isn’t going through these painful days alone, a feeling she generously extends to an audience who will likely see a relative or even themselves in the family’s desire to hold onto a time when everything was at its best.

Both tremendously moving and uproariously funny, “Dick Johnson is Dead” may be most admirable for allowing one to be in the truly lovely company of a most delightful and gregarious family, and with the film’s debut on Netflix this week, it was a joy to spend just a little more time with Johnson to talk about how she was able to create a responsive production process that could allow for the type of discoveries she’d traditionally make in observational docs when certain scenes were staged, the ongoing vitality of movies and how they become a form of collective memory and finding herself in the unusual position of looking forward to planning her father’s funeral.

Oh my God, that was a particularly amazing one. There was something about that one in Salt Lake that was really strong and there was an amazing moment after that Q & A [because] I’ve had this worry about the film like what about the person whose father really did die in the way that Dad dies in the movie? It happened at that screening. This woman came up and said, “My father died falling down the stairs and my son, who we later learned had schizophrenia, pushed me down the stairs… and she said, “And that was one of the funniest movies I’ve ever seen.” [laughs] And we were laughing and hugging, her and me, not knowing the pandemic was around the corner. But it affirms for me this thing that when people know pain, some people really know humor too.

When you have to stage these “deaths,” was it interesting to reverse engineer the process a bit where you’re creating an experience and capturing the reaction rather than letting it unfold naturally?

What’s interesting is that’s not exactly how it functioned. There’s certainly reverse-engineering in this, but I’m deeply interested in the unexpected, so as a documentarian, there’s all of these moments where something hits you — blindsights you — and you’re like, “Oh, this is going to be in the movie because I didn’t see it coming and the audience won’t see it coming.” That I’m familiar with from documentary camerawork, and what I know about dementia is you’re not going to see it coming. It’s deeply unpredictable and [I wondered] is there a way to create a process that allows us to tap into deep unpredictability and then be able to build on it?

I didn’t know what deaths I was going to do, I didn’t know I was going to film scenes [set in] heaven. I didn’t know the way the film was going to go in any way. What I was committed to was this process of not knowing with the team and that we would build it in this iterative back-and-forth in which we edited a scene and then thought, what death could we make happen in relation to this scene? When it didn’t work, then we said, “Can we do it with VFX?” So it was like an accumulation, and in some weird way, it wasn’t so dissimilar from “Cameraperson” where we accumulated and in the accumulation, we learned things that then we changed and integrated what we learned into what we were building. It was really wonderful to share the process again with [my editor] Nels Bangerter, who’s so open to that, but there was a moment where I like dropped a bowling ball on this movie late in the process — we had the breakthroughs that we did around the funeral scene that came in at the 11th hour — and he was like, “Noooo…” [laughs] “We can’t break it again.” And “I’m like, “We have to break it again.”

Oh, all! What was such a delightful surprise was to actually get the support of Netflix early and to have money upfront, so I was ready to spend it. I was going to go to Hong Kong, I was going to go to Ghana. I was going to take my Dad all these places and then it was like, “Boom, the dementia is far enough progressed that I can’t do that. I can’t put my Dad out on an ice floe.” So there’s always this resistance, right? If you get fast and cheap, you don’t have easy. If you’ve got time and money, your principal star can’t remember what you just asked him. So the way life resists being controlled, and the future resists being known, is one of the big questions of this movie.

When this is such a personal story, who do you look to for objectivity, if you’re even looking for that, or just pulling things out of you?

I would say I’m looking for people who can see things I can’t see. Marilyn Ness, one of the producers, said to me, “Some people, this movie is a fantasy for them. They didn’t get to have a relationship like this with a parent and this movie will be a different movie for them than it is for the people that had loving and connected relationships with parents, so can it leave the space for that?” Comments like that [helped], and also I would say looking at the things that I have loved that have allowed me to transgress my own limitations or fears or shame about making mistakes – the way “Jackass” or “Harold and Maude” make me laugh, or “Groundhog Day” in some ways actually helped me cope with religion. [laughs] There’s these funny ways in which movies liberate you. They let you go into territory you think you can’t go into and they do that on an experiential level, so imagining how to craft an experience out of the experience I was having with all these wonderful collaborators was really, really engaging intellectually and emotionally.

I was actually curious how you wanted to engage with religion because the family’s connection to Seventh Day Adventism is prominent, as is the idea of heaven, but I had heard there was a scene in an early cut involving your dad’s turn towards atheism in later life.

I’m happy to engage with it. It’s really because that scene couldn’t quite hold its weight [that it’s not in the film], but certainly he was ready to put it in and I was ready to put it in. I go back and forth on that, like “Oh, missed opportunity,” but I want this movie to let people in who are more comfortable with known things and more boundaried thinking, so in some ways, it makes me really happy not to have included the atheism because I welcome all Seventh Day Adventists and religiously believing people to watch this movie because I do think it is about the power of faith and in some ways the limitations of faith and the way in which those of us who are here on this earth and stare the difficult things in the face and own them and don’t deny them is freeing in ways that sometimes people believe religion is freeing. There’s a provocation in the movie, but also an invitation.

Was your father actually actively pitching ideas for the movie, like what his idea for heaven might be?

We watched tons of movies together. He introduced me to the cartoons of Charles Addams, so [for the film] we’d look through the cartoon book and he’d be like, “Could we do that?” [laughs] So he was incredibly active as were my children. We had lots of dinner conversations with my two [kids] and my dad about ways that we could kill him, which was really hilarious and fun for everybody. It gave us a way to live with the dementia and be playful about it and live with the moviemaking.

It’s so funny when you were saying that, I thought you were going to ask me about “Cameraperson” and the snowy window where the snow falls off the roof…

Oh my gosh, I hadn’t connected those two shots!

I hadn’t either! And you just connected them for me, which makes it even more magical, because that was the moment of Kathy Leichter’s mom making her presence known from beyond [in a scene excerpted in “Cameraperson” from Leichter’s “Here One Day,” which Johnson was a cinematographer on]. When we were filming with my dad, it started snowing. It was a very unexpected snow, and I saw his reflection in the window and it reminded me of “The Wizard of Oz,” so I was filming the reflection and we were trapped in the office because of the snow – we couldn’t get out – and I love where I’m trapped somewhere when I’m filming and I have to go beyond what is the obvious thing to film. I can just mess around, so I just started racking the focus and watching the snowflakes, realizing that in and outness — that fading away, and the image being something almost gone already, but being legible — was such a visual metaphor of what was happening to my father’s mind with dementia.

It was a push in [with the camera], [so I wondered] how does this scene be more than it is? And it was grafting those two pieces of footage together, the literal and not literal, that was a delight in the edit room. It’s like “Oooh, that works,” and I think there are these magical resonances that happen between movies that we have seen and don’t remember matter to us that float around in my mind and reappear — “The Wizard of Oz” was there for me in that moment.

It makes me feel more comfortable with the idea of losing because I get to keep some of it. In the making of “Cameraperson,” I realized I was making the film in some ways for my children, so my children would know me. The Bosnian mother tells me that and I figure that out in the course of making “Cameraperson.” This one, I knew my children are too young to remember who my father was without the dementia and the dementia was so powerful with my mom, I could barely remember what she was like before it, so I really did want to create something for the kids so that they would be able to remember him. But what’s so deep is the dementia was already ahead of us, so there’s this way in which this task is this impossible task, yet I can handle the loss of things, knowing that images live in some way. It helps me feel and imagine new things — like your [last] question gave me a new connection, which makes me so happy because I love when the connections happen — and I think of images as relationships. They are not static in time. They are shifting in time. And these images will go on after everyone who made them and everyone who is in them is dead. The images continue the relationships with the people who might see them, so your relationship to the images that we as a group of people have made, we now remake them together, so I love the aliveness of it.

“Dick Johnson is Dead” is now streaming on Netflix.