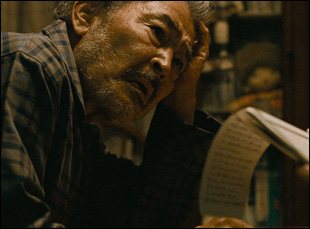

“Great Absence” suggests it’s a different film than the one that will follow when it opens with a SWAT team descending on a house in a quiet gated community in Kyushu, Japan, creeping up slowly out of fear of what retaliation may come when it’s revealed to be nothing more than an elderly salaryman. If the finely dressed Yohji (Tatsuya Fuji) appears miscast in a police thriller, his son Takashi (Mirai Moriyama), an actor by trade, is thrust into a role that he hardly wants upon learning that his father brought the cops to his door with guns in hands after calling in a bomb threat due to his dementia. The two have been estranged for years, long enough for Yohji to take a partner in Naomi (Hideko Hara) that Takashi is completely unaware of and his own wife Yuki (Yoko Maki) only knows the broad strokes about Yohji, having to wonder whether he was always this taciturn when they go to visit or if it’s a result of his condition.

Circumstances may be shifting under the family’s feet in “Great Absence,” but Kei Chika-ura’s prismatic third feature slips through time as the director shows how the relationship between Yohji and Takashi deteriorated before the former’s health did and how it continually poisoned what care could be provided to him when Naomi was hospitalized herself with a heart defect. When Yohji finds himself isolated and in need of being set up at a nursing facility, Takashi ends up acting as a surrogate, communicating the needs and wants of his father whom he doesn’t trust with people that don’t trust him after he’s burned so many bridges, and while Takashi plans for Yohji’s future care, he gradually comes to learn of his past as he cleans up the home he’ll have to sell, piecing together not only reasons why their relationship fell apart but so many others that Yohji failed at nurturing, perhaps leading to a concern that Takashi’s repeating history when in tending to his responsibilities as a son, he gives less attention to his marriage.

Beautifully shot by “After Life” and “Still the Water” cinematographer Yutaka Yamazaki with history emerging from every corner of the frame due to the detailed work of production designer Sango Nakamura, the film uses a wide screen to present generations commingling with one another while finding its characters paralyzed by not feeling as if they belong to one or another when either memories or the lack of them prevents from being completely present. Following the film’s premiere at the Toronto Film Festival with the help of a translator, Chika-ura and Moriyama spoke about their collaboration on the film, which was rooted in the filmmaker’s personal experience, and how a blend of real life and fiction could bring about an undeniable feeling of truth in the drama.

Kei Chika-ura: The direct inspiration was my own experience of my own father suddenly developing dementia. At that time, I was trying to film another film and had finished writing the script, but for some reason I felt like I couldn’t get over this profound experience unless I digested it. I wouldn’t be able to move on, so I decided to completely change my plans and create a work based on this experience, and I thought that if I could do that, I would like to make something that could work as entertainment, even though it might not be a fun movie. That’s what got me started.

What was it like to get involved in a story that was so personal to the director, Mirai? Was the fact a character is an actor something that helped you find your way in?

Mirai Moriyama: It was a bit of a difficult situation, but based on my personal experience with Mr. K, I learned about emotions by talking with [him] and I also did some research on dementia. The situation of being an actor was one of the first things I encountered from the screenplay stage. But I think there is something fundamental in this character’s vocation and the fact that this letter is in the diary that Naomi has kept for a long time, [there’s] the act of reciting the letter, which means treating it in a theatrical way and I wanted to use that reading as a key bridge as I thought a lot about how to link the characters’ professions — although the context is different, [my character] is alone. If he says something out loud, he can get into the same scene and I thought it would be interesting if the boundaries were dissolved. When I was watching the film [earlier] today and I saw the moment it actually disappeared, I thought “Oh, that’s good.” The key to getting involved with people is to get involved like an actor in the huge world they create, and to develop that line within yourself, or rather to build on that line.

Kei Chika-ura: I simply said that I had a personal experience like this, but I didn’t think it would have that much of an impact on how he prepared for the role. But Mr. Moriyama said, “Now that I think about it, I realized that when I was building the role, that was one of the major pieces of information that I used as a key. The build-up was extremely delicate. He is me.

Beyond the diary, the house is littered with physical artifacts that seem like they must’ve been quite helpful in shaping a performance. What was the process of production design like on this?

Mirai Moriyama: This is actually Mr. K’s parent’s partner’s home.

Wow.

Kei Chika-ura: My father suddenly developed dementia, and when he entered the facility, the house was empty and before it fell into disrepair, I thought it would be great if a lot of people could come in and feel what it was like before the house collapses. I decided to take a picture of the house and when I went to tell my father that I wanted to make a movie, he stood there and was very happy and said to me, like a child, “Really?” Basically, the house is the foundation [for the entire story]. Of course, our department director was designing, processing, stripping, but it was an authentic place, and it had that kind of atmosphere, which was very important for that sense of the atmosphere of life.

Mirai Moriyama: The location was really nice, but more than anything, the design of that notebook was really amazing. It was impressive, and the extent to which the props and art are incorporated in movies varies quite a lot depending on the scene, but when it comes to that notebook, from the first page to the very last page, it had all the things Naomi wrote and the details were amazing. All the letters written and sent by Yoji pasted on it, I thought it was more true than the real thing. That really was everything to me.

Mirai Moriyama: That scene was originally a workshop scene, from the play “Exit the King”’ by [Eugene] Ionesco and read it as a workshop, and [the intent was to reflect] the reality of doing a workshop, but I was curious about this scene in a different way. “Exit the King” is about a dying king who had a lot of authority up until that point, but it’s a story where things are stripped away, things disappear, people disappear, and in the end, you end up truly alone, losing everything and sitting on a throne. And I felt that this very directly connected to the main story. We talked with the stage director [conducting the workshop in the scene] and the staff, and it was a very interesting process, and after discussing how we should approach this book and incorporate it into “Great Absence,” we ended up using a structure in which we received the material and created it together while interacting there. It felt more like a real creation than a rehearsal.

Kei Chika-ura: At first [that introductory scene] was much more flat, static and artificial – a little bit further away from authenticity. What made it what it is now is that [Mirai] asked questions about it and from there, I made a lot of preparations, and I thought, “This is how I’m going to do it,” and I invited this stage director [who was only supposed to be in the scene as an actor] to come and create with me. We actually spent a whole day creating [the scene together], and that’s what I wanted – to become more of an observer. We asked if we could shoot for a couple of cuts and I only took two shots at the very end, maybe three, [thinking] I was running out of time. [The stage director] he would let me shoot 3 shots with the set-up, and I used the 3 shots I took — one where the director and producer are looking at [Mirai], and two on the floor, [from] a mobile phone and the last photo is a back shot. It felt like I was able to enter the creation [of a scene], which I think is a very rare experience and [the stage director] gave me a deeper understanding of the relationship between the director and the leading actor. When I think about it, I feel so grateful every time I see that scene. I’m a grateful collaborator.

“Great Absence” does not yet have U.S. distribution.