There are things involved in making a movie that you can never be entirely prepared for as Iram Parveen Bilal found out, even after already having had the experience of making a feature before “I’ll Meet You There.”

To ensure that Qavi Khan, Bilal’s first choice for the role of a grandfather whose arrival in America throws the relationship between his son and granddaughter living in Chicago into disarray, would make it from Pakistan on an O1 visa, there was a mad scramble to find an extra $5000 on a budget that was already stretched to its limits. The director/producer had been sorting through Excel spreadsheets while trying to keep her creative focus intact, finding that even after scrounging up the money, it may be difficult when it too would come from Pakistan to transfer over smoothly. Still, Bilal is the type of filmmaker for whom when there’s a will, there’s a way, which is how she ended up in a money drop in Williamsburg where it felt like she was pulling off ransom exchange.

“I’m in New York in pre-production, and this person’s giving me $10,000 in a black plastic bag and I’m counting in a Mexican restaurant, so Qavi is able to come and we were able to house him in an AirBNB,” recalls Bilal, still incredulous about the whole affair.

If the writer/director felt compelled to go to such great lengths to make “I’ll Meet You There,” it was because she knew what a strong story she had to tell with the Windy City-set tale of Majeed (Faran Tahir), a police officer and his daughter Dua (Nikita Tewani), whose pursuit of a career in dance like her late mother isn’t much of an issue until Baba (Khan) shows up, wondering why his family isn’t more mindful of their religious roots from Pakistan. This is a particularly complicated question when Majeed is involved in the undercover investigation of a local mosque suspected of laundering money for terrorists, having to deal with both how he feels he’s seen by fellow officers but also seeing enough evidence that there may be cause for concern, and as he feels more disconnected from his culture, Dua is inspired to move towards it more with her grandfather’s encouragement, creating distance in a relationship with her father that had previously been so close.

The film, which was intended to premiere at SXSW last year before it became a casualty of the coronavirus, is rich in its complexity, so much so that Bilal has embraced the prospect of an unconventional rollout during this time when theaters largely remain off-limits by creating a series of special screenings this week and next accompanied by discussions on the film’s music and dance (Feb. 4), immigration (moderated by Jose Antonio Vargas on Feb. 5), and its sensational cinematography (Feb. 6), culminating with its premiere next week on February 11th, after which it’ll be available on VOD. It’s one thing to set up an exciting lineup of events, but “I’ll Meet You There” should be seen as one in itself when it finds satisfying ways to tackle complicated issues of cultural identity and is bound to sweep audiences off their feet with its sequences where Dua performs the traditional South Asian Kathak dance. On the eve of the film’s release, Bilal spoke of how difficult yet rewarding it was to bring her vision to the screen, how she created a story that wasn’t autobiographical to touch on so many of the emotions she’s felt as a Pakistani-American, and finding aesthetically inventive ways to express what the characters are feeling throughout.

I came from an engineering background and went to a film program that was like an MBA for filmmakers. There was a writing class in that and I’d written essays in high school, but I’d never written a screenplay. This was around 2006, so we were a little far away from 9/11, but the Iraq war and the Patriot Act were in full swing, and I wanted to write something personal. When I was at Caltech, an Iranian friend of mine who used to wear the hijab took her hijab off because of hate crimes, and I distinctly remember her dad was picked up from the masjid after morning prayers. Later, the only charges they could bring against him were that he had incorrectly filed his taxes, but they were treating him like a terrorist. I remember going to the hearings in Pasadena in the court and just being shocked.

Being in my teens and early twenties on the west coast and being a female, I knew friends who’d come from Pakistan and had the FBI call their dorm rooms, so this was internalized in some ways, and I remember [being at] a community event [where] this very orthodox-looking Muslim [person] was wearing a cop uniform, and I just remember thinking, “Oh my gosh, I would not want to be in his shoes right now” because that was a time where being Muslim, you were guilty until proven innocent and suddenly there was this big spotlight, even in the Muslim community. Suddenly it was like, “Oh my God, what kind of Muslim are you?” Because the moment you enter a room everyone’s interested in your religion and you have to be the expert in the room, so within the community, everybody started planting their flags.

Within my family, for example, we would have these co-ed weddings, and in the program of the wedding, we had to have the food before the dancing so that the conservative part of the family would leave after dinner and then the dancing would start. If you look at it in terms of politics, this all leads back to the Soviet war in the late ‘70s, and then the employment opportunities in South Asia coming from the United Arab Emirates, and in the early ‘90s, a lot of men specifically went to Dubai and the UAE to work, and they were bringing back this more conservative type of Islam. For instance, growing up in Pakistan, I hardly saw women in burkas, but now, I see a lot of hijabs and burkas, and even in my family, being the youngest of three girls, my oldest sister who actually taught me how to dance, she now thinks singing and dancing are not Islamic ways of being. I on the other hand, seem to have gone to the other end of the spectrum and become perhaps, more Sufi.

So when I wrote [this] in film school, it was just very much post 9/11 and because it was very personal and just hard because it was the first script I wrote, I kept putting it away. I was hired to do other things – I went away to make my first feature, but I would keep submitting this to labs and there was obviously something that kept hitting people because I would keep getting in, so I kept saying, “Okay, well, I guess I need to rewrite it.” As my sister became more conservative, this angle of all the things I wanted to say to her [came in].

Also, when you’re middle class, which is what I was, you didn’t have that nuanced understanding of art. My mother’s a physicist and my dad’s a chemistry professor, so art as a profession wasn’t really a possibility to even discuss at home. I felt that art was relegated mostly to the elites or to the street. I followed the traditional path and came to school to Caltech to be an engineer. My parents were forward thinking in that – they sent their 17 year old to school. After my undergrad at Caltech, I traveled around the world as a Watson fellow — I backpacked in India, and I studied why people dance. It was my personal way of trying to understand the taboo, because what drove me nuts was in family gatherings, we would all be watching these Bollywood heroines dancing and yet if I wanted to be a professional dancer, I just knew the opposition that would garner.

Back to the film, there were these two things colliding; one, the reality of post 9/11 America and the notion of extremism and art and expressionism, and as the years moved on and I grew up, the script kept changing. It became very personal and in some ways, I would say [that may be] a negative of the movie when it was my first script, and as independent filmmakers, we never know when we’re going to get a chance to make something again, so we just try and figure out, “What is the way I can say a little bit in everything?”

When I look at the film, people would think, “Oh, [you’re] Dua…” Because I’m a girl, but I actually connect so much more with Majeed. I’m the one who’s got the old parents back home. I’m the one who came when I was 17. But I’ve also seen the struggle of Dua. So there’s a little bit of me in Majeed and a little bit of me in Dua. And what we ended up doing is to embrace it more as an ensemble piece and bring these issues that each person was dealing with.

Typically, you see Majeed as the conservative father in any other movie, but the stroke of genius is having Baba come in and change the relationships between father and daughter. Was he there from the start?

What you call a stroke of genius is exactly why it has been so difficult for me to get this film financed because everybody would say, “Well…” Because it was too gray for them. They needed to have it be black and white, or they would be like, “Well, something needs to be wrong in the mosque.” And I would be like, “Well, why would I be telling that story?” From the beginning, I have always thought the notion of the oppressed Muslim woman was so overdone and it’s also not so black and white as it is shown quite often. A lot of times when patriarchy is at its worst actually, women are the [strict] ones towards other women. In an earlier draft, [Dua] always had a great relationship with the dad and the mom was alive and she clashed more with her mother. Anyhow, I was so done with seeing that trope and I just felt that the intergenerational conflict [was more interesting].

You have been pretty frank about some of the horror stories regarding the financing of this and I had heard in the casting that you had gone out to Bollywood actors first as a commercial consideration, which is interesting because it seems an extension of the themes of the film when the production was living between two worlds as an American production.

This is what I’ve been saying from the beginning – [that] the reason this film is finding a hard time in the financing and traditional distribution landscape is because it is living my life, which is I’m too brown for American stories and I’m too white for stories in South

Asia. This is exactly what is happening with this film. It’s not a coincidence that there are these verticals where things need to fit. For instance, we were trying to finance it through one of the major agencies, and their way of financing seemed completely wrong to me. They were trying to pre sell the movie to India, and I thought “This is a very American film [and besides it’s] Pakistani content. India’s not even going to touch with a 10 foot pole.” Then the other issue was – and I despise that phrase – the need for named stars. For instance, Faran Tahir is a very well-known face for people, but he’s not going to be bankable in your terms because you hardly ever gave him a role meaty enough where he could have actually displayed his brilliant acting chops, so it’s this constant systemic cycle of leaving BIPOC out of the possibility to become big enough to be bankable in their terms.

Faran, by the way, is somebody I always knew was right. I knew him through some Pakistani circles and we’ve been wanting to work together. Two years [before starting production] a year before the crowdfunding launch and right after the Muslim ban, he drove from San Diego to be at a table read and I told him, I said, “I can’t attach you yet because I need to go through the financing,” so he always understood the economics of this business we’re in and I had to go around it. I never had the fortune of working with casting directors before and because the community is so small, in the past I’ve been able to cast on my own. But here, Sunday Boling and Meg Morman did an incredible job building out the cast for us. They found Nikita [who plays Dua] through a traditional audition. From the first audition I saw of hers, I was just like, “Oh my God, this person’s so raw. She’s amazing.” You don’t often find people from a Hindu background who do Kathak. I’m in love with this cast. They really pulled us through. They gave it everything, the entire crew and the cast. I’m just very, very grateful.

I loved seeing Sheetal Seth as Dua’s dance instructor because she was in a movie I loved from years ago, “ABCD”…

And you know what’s so funny? Sheetal and Faran are siblings in that movie. That’s the first film they did together and this is their reunion. Because this film has been in the works forever, when it was in the Film Independent Directors Lab, Sheetal still used to live in LA and I remember she came in for an audition. We were shooting a few scenes in the movie just for the lab, and she still came for the audition even though she knew that she couldn’t make [the movie because of the schedule], but she just wanted to interact with me, so we were connected and we have a common friend, Tanuj Chopra, whose films you’re probably familiar with, and [when our production] was down to the wire, I thought “this has to be Sheetal. I don’t see anybody else who could play it so well.” And she just wrapped “Hummingbird,” a film with Tanuj, and she flew to New York, we had a lunch and I told her, “This is how much we can pay,” and I went home, fingers and toes crossed, and I think a big part of her [agreeing to be in the film] was the cast we had assembled. She was very excited to work with Faran again, and she loved the script. When something has to happen, it just feels like all the forces align from everywhere.

It was such an insane process to just put this together. And I remember we did an in character dinner with her, with Nikita, Qavi and Faran and it really was a family. To this day, Nikita will sign off saying, “Miss you, love you” and that’s not normal for a director and actor. Everybody was so connected. Sheetal’s shoot was only four days, but I remember she was so emotional leaving the set. Because when a film like this happens, it really truly is fate. You’re all holding each other. Basically it’s a skydive, you’re just falling and just holding each other.

That’s what I’m really excited to continue working on in my career is just being so prepared and just throwing it all away when the elements are in place and just trusting in the magic unfolding. That’s what I mean by the skydive, you really just have to be in freefall, and be fully mindful, and play. For example, Sheetal, Nikita, and I met for a rehearsal, and Sheetal was very prepared, but she was just kind of a little [walking on] eggshells, working for someone. And I said, “No.” I said, “Tell me all your ideas” and if I could defend something, I would defend it, but if I couldn’t, I’d be like, “You do have a point. Let’s just go with it.”

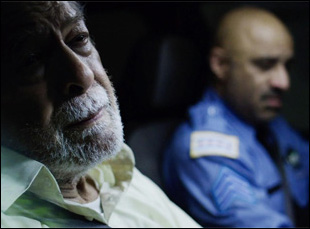

The most special collaboration that we did was on the Urdu dialogue because I grew up speaking Urdu, but I don’t have the diction Qavi Khan has or Faran has, so I empowered them down to every single dialogue, should this line be said in Urdu or English between the father and the son? Or let’s make it very important and intentional. This line, if you switch this to English, it’s intentional. For example, there’s a line where Faran and Qavi fighting in the jail, and that’s my favorite scene in the movie, when Qavi says at the end in English, “I’m done here,” and on the surface you could think he’s saying it just so that the guard understands, “I’m done here,” but there’s a reason why he says it in English. It was so much fun with them. Every film you’re like “Oh, but this film I’ll have so much rehearsal time,” but it’s never enough. You have to be just present in the moment. We had enough touch points so that when we were in the rigor of the shoot, I could just say something and they would get it because they’re so good at their craft.

The idea of movement in the film naturally connects with dance, but there’s something exciting about having certain styles of camerawork associated with specific characters and how there’s a blur if they cross paths. How did you figure out the aesthetic for this?

It was very planned, and it was based on the scene and it changes with character and at what point the camera language of character A and B intersect, if at all. Or if both the characters are in the same scene, whose camera language guides the scene because you can do it. Majeed is primarily handheld, and Dua is primarily steadicam. Or everything with Baba is very still because Baba is rigid. We played with step printing and also framerate and shutter [speed], [which] had to do with the moments of escape that were visceral. Every time [Dua’s] dancing, or even in a dance when she escapes, that is when we would engage with step printing and Anthony and I got exactly what we wanted. The [frame] rate was a choice because it’s like when crazy shit happens, time slows down and things are in slow motion, so we used it for that.

Anthony and I have done a lot of films together, so have a short hand. I gift him a book usually, so we have matching books. In fact, he’s been attached on this project so long that we first did the shot list based on the script without any locations. All the heads of departments were attached for two years before we started filming because we were almost about to film twice, so we were always bouncing things back and forth. In fact, the production designer was shooting something else in New York, and I was visiting trying to get life rights for another film subject, and at that point, we were still going to shoot in Chicago, and we just walked to Jackson Heights and he looked at me and I looked at him and I said, “You know what? Better crew in New York. Let’s just shoot in New York instead of Chicago.”

Then as the locations were getting locked, Anthony and I would re-shot list. And much to [Anthony’s] chagrin, and also budgetary reasons, we were both living in one two-bedroom Airbnb, but I actually think it’s smart because we would come back every night, we’d take our showers, sit down, and we would write the shot list for the next day and the day after. The day would go so fast, I felt like we were ninjas with our backs tied just dealing with things coming at us; I would look at Anthony and we were just on the same page. That is the only way we would find slivers of time where we could experiment or we were able to achieve the things we needed to.

I had heard the edit was a work in progress alongside the music so they actually informed each other. How did that process play out?

Remember I told you about the trip I took in June to Pakistan in 2018? I attached the composers and I asked them to start because I needed music for the choreography and the sequences we had to shoot. This is done a lot in Bollywood, but I had never done it before, and while I was doing that, I asked them to create threads of character themes because it can sometimes help [the actors]. I had definitely had something for Dua, and [once] we had that music, that went to the choreographer so that she could choreograph the scenes.

Then [during] editing, I go to Pakistan again and we are using some of the music and some temp and I showed the composers the temp music and they’re creating and sending me stuff as we are finessing the edit. Because of the dance element, the collaboration started early with them, and working in South Asia, people just need to be [working together] in person, so I spent four or five days in person just watching the rough cuts with them and just explaining what I needed.

There’s something about breaking bread and having chai doing it together. One of my favorite pieces of the movie is the swell at the end [of the film], and I still remember that I was at the composer’s house and there were these two composers, one was very much on the electronics side of things and the other guy was very Sufi, into Qawwali traditions, so I told him, “This is your cue. I need that depth because this cue needs to lead me to reveal the [title of the film]”. And I went off and I was having chai and I was outside with the producers, and I came back in and [the composer] said, “I only want Iram to hear it first.” And I went into the room and I heard it and I burst into tears. This composer and I were both sobbing, and everybody came in and was like, “What the hell just happened?” It was a very awkward moment, but he and I in that moment just had spiritual alignment. It was beautiful. Thanks to that soul-stimulating music cue, most people cry at that point in the movie and it’s just so beautiful.

“I’ll Meet You There” will be screening virtually with a series of special events attached beginning on February 3rd. A full list is here.