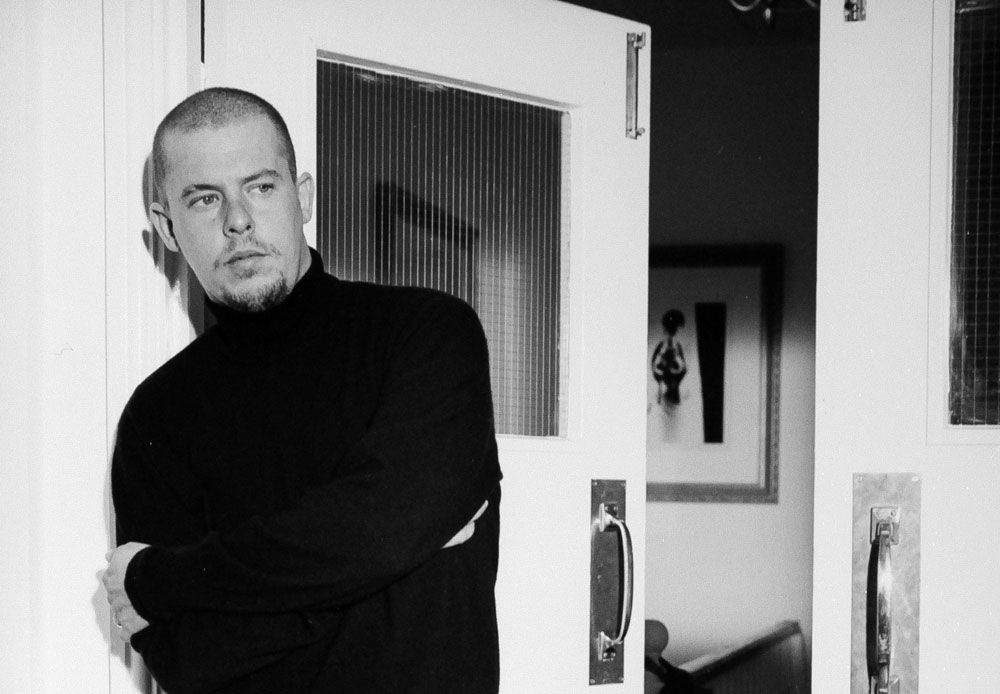

In the rather sly opening shot of “McQueen,” one sees a fish swimming around in aquarium, perhaps a nod to the groundbreaking final show Lee McQueen would stage, “Plato’s Atlantis,” in which the fashion designer would imply humanity would have to live underwater, or the fact that ever since he started the Alexander McQueen label, his own life might’ve taken the form of a fishbowl as his attention-grabbing outfits brought intense scrutiny to the person making them. But most of all, the camcorder grade footage shot inside an apartment suggests an intimacy with its subject that had only been enjoyed by those closest to him before, and after his legend grew in the wake of his death in 2010, a welcome reminder of the boy from the East End of London who made good and despite his ability to create otherworldly garments was decidedly earthbound.

Ian Bonhôte and co-director Peter Ettedgui are able to show both sides of the iconic designer, engaging in the flashy, devil may care aesthetic choices that McQueen surely would’ve appreciated himself, often projecting imagery from his myriad influences onto the surface of a gold-plated skull that the designer was so fond of and blasting Michael Nyman music (a favorite of McQueen’s) to accompany his steady march from being a tailor on Saville Row to a top brand for Givenchy and Gucci, while quietly reconstructing his personal evolution through interviews with friends and family as well as first-person testimony through rare archival footage. Allowing one to get to know Lee as much as the name he would come to be known for around the world through his brand Alexander McQueen, the film celebrates the women that broadened his horizons, namely his mother Joyce and the fashion editor Isabella Blow, and draws a clear line between his passions and his designs, reanimating his fanciful creations with the understanding of what part of himself he was putting into them.

As “McQueen” bursts into theaters, Bonhôte and Ettedgui spoke about how they took inspiration from McQueen’s shows and were able to compile such revealing footage of the designer as well as prioritizing the ability for McQueen to speak for himself, even from beyond the grave.

Ian Bonhôte: I got approached to direct the film and Peter came onboard as a writer for the structure and it was very clear that we were making the film together. I had never done a documentary before, and Peter had, and it became clear that you need all hands on deck with a documentary. There are less clear roles than in narrative filmmaking [with] the collage you create and the trust you need to build with the contributors as well as the investigating work that you have to do through the archive. It is not as defined and what’s interesting as well is we always approached the film as a movie. It’s not like we’re going to interview a bunch of people and let’s see what they tell us. One of our mottos was emotion over information, so anything that we were trying to tell in the film had to have an emotional impact or follow an emotional beat that was part of the narrative. [With] Peter having more experience on that side than I did, it just naturally fell into place that we were making the film together. And we had a really short time as well.

Peter Ettedgui: It was very intense and we would always push each other to make something a bit better. We did know each other a little bit beforehand and I think McQueen very much brought us together as a subject. I worked on [“Listen to Me, Marlon”] a documentary about the great Marlon Brando and [once] you do that, you think that’s it. There’s no one else you could make a film about that would top that. But somebody mentioned to me that there was a dramatized version of McQueen’s life happening and at that moment, I thought that’s such a pity because McQueen’s such the right person to follow Brando with because [he was] someone who was so creative and had such an extraordinary life [where he] packed so much into it. When I heard that Ian was attached to this film, we basically started talking immediately about it and those conversations became the filmmaking and continuing now with you.

Peter Ettedgui: It was the first thing [because] McQueen said, “If you want to know me, look at my work” and of the work he did, the shows were [what] he cared about more than anything else. I think if somebody told him you’re not going to do any more shows, I think he would’ve quit fashion at that point because it would’ve had no meaning for him beyond that. He was a brilliant tailor, craftsman, and designer, but what really got him out of bed in the morning was putting on these shows that were more like performance art than traditional runway shows.

Ian Bonhôte: He needed to get emotion from people and it was just about creating clothing and selling it to people, he wouldn’t have experienced firsthand the emotional response. In the shows themselves, he had an audience there, which was as Peter said, was close to performance art or a concert and it was interesting [because] shows were only witnessed by a small amount of people. You didn’t have social media where people could share straight away what they see on the runway. [At] runway shows now, people don’t even look at it, they just look through their phone where back then, people would be coming out of a McQueen show and talking about it and made it so hyped that people would fight to see the following show even more.

Peter Ettedgui: And they would literally fight.

Ian Bonhôte: Yeah, so all of those elements made what people would say about Lee just keep on growing and growing and make him [into] an icon very quickly and we wanted to go behind the icon because we always feel that it’s very dangerous if someone passes very quickly, you hear a certain story. We felt we needed to make sure it was an honest portrait of Lee with the ups and the downs, the fun and the dark. One of the contributors told us, “If you know about Lee, you need to know about the lightness, but you needed to talk about the darkness, so that very much dictated our direction.

I understand the McQueen estate wasn’t onboard at first and obviously they came around since you interview members of his family, but did initially not having that guiding the project turn out to be a blessing in disguise.

Peter Ettedgui: Yeah, when you say the McQueen estate, there are different bits of the McQueen legacy — there’s the brand, the house of Alexander McQueen, and then there’s the family and then there’s his foundation, which sits somewhere between the two. We felt if we were going to carry off that personal approach, we had to have the family onboard and we went to see the brand because we felt we needed to let them know what we were doing and it turned out that they absolutely did not want to do any form of collaboration because they had done “Savage Beauty,” the show at the Met and at the V & A in London, and they needed to put the focus on the present creative director Sarah Burton quite rightly. As you say, the problem here is if you do a film with the cooperation of Alexander McQueen the brand, then you are making a brand film and then you are going to be controlled because they’re going to quite rightly say, “Well, we’re not going to want you to explore this aspect of this personality” or “We don’t want you to interview this person, we want you to interview that person,” and very subtly, your film is going to be something that becomes a big commercial for the brand, which is just so far away from what we wanted to do.

Ian Bonhôte: And that actually emphasizes the fact that we don’t feel like we made a fashion film because we didn’t make a film about a brand. We made a film about a creative designer who created a brand, but that’s one of the many things that he’s done and one of many parts of his life’s journey.

Ian Bonhôte: They were there from early stages, from our first research to reading a lot. It was clear that Isabella Blow had played a massive role in his life and even more so, his mother. [Joyce] introduced him to storytelling and she always pushed him. Lee came from a very working class background in the East End of London and in England, [that] doesn’t always allow for the ability to be extremely cultivated or go to a museum where in Lee’s case, the mom pushed the children to read a lot. She brought them to the V & A, she was an advocate of culture. And that’s not always the case in many working class families, so not only did she adore him and completely embrace him and accepted him as who he was, but she nurtured him. In a lot of great sports people or artists, the parents play a massive role and in this case, the parents never left. And Isabella Blow… Janet, Lee’s sister says it, she slotted very well as a best friend and a sister…

Peter Ettedgui: More like a member of the family almost. She was from a very posh, aristocratic background, but she loved going to the East End and going and having a cup of tea with Lee’s mom. She was close to all of them and a huge champion for McQueen. She put him in a position where he had certain opportunities that people from his background didn’t normally have and she introduced him to art and art history, which he knew a tremendous amount about. We were told the other day by a photographer that had documented that early period that Lee would come and stay in her and her husband’s beautiful house in Glouchester and they’d go out to the village to the butcher [shop] and Izzy would introduce Lee to the butcher as “the greatest fashion designer of the next century.” [laughs] So it didn’t matter who it was. She was absolutely going to push him up and make him feel great about himself. She saw what he had, which was this very beguiling mixture of tradition because he mastered the craft of being a tailor in such detail on one hand and subversion — the fact that he had this like darker side to his personality. He was a rebel. He could produce a piece of clothing that was traditional and beautiful on one hand and turn the tradition inside out on the other. Broke all the rules.

Ian Bonhôte: Definitely. Documentaries are [typically] made up of a lot of interviews, but an audience comes to see Lee, so they want to hear from Lee, so however much we could get other people to say things, we always tried to make sure that Lee would confirm what they were saying or actually start the argument that other people would talk about. One thing that we feel that people really take from the film is the home footage [where you] see Lee very up close and in a more candid way because when you do an interview, you can potentially censor yourself or you can project an aspect, and as Peter says, there was tradition [with Lee], but at the same time, he’s slightly punk in the way he’d say things [to get a rise], but on the other hand, you see the soft side of him where he plays with the dogs and he was really good friend to his friends. While we were making the film, we realized how much people loved him and still now feel emotionally still in pain for his passing.

Peter Ettedgui: But going back to the archival, when you start a documentary, like the Brando documentary, of course we did archive research, but basically, we had this incredible honey pot of personal recordings of Brando that generated the whole project. This one was completely mad. We didn’t have anything. in a sense, we were being like two detectives with our archive producer and researcher, there were four detectives — it was like a detective agency! — trying to track down everything that nobody had ever seen before. We looked absolutely everywhere for everything so we went to about 200 sources, from private [collectors] to broadcasters to these small companies that covered fashion in the 1990s, and we wound up bringing stuff in from 150 of them, and it was an incredible operation because if you want to make a really incredible cool cinema documentary, the thing you have to have is great archive that no one has ever seen before. There was the stuff that everyone could see on YouTube, but, Ian mentioned before the notion of collage, and it’s like that. That’s what makes it such an exciting medium in the digital age is that we have sequences in which we’re using a mixture of Hi-8 home camera footage with broadcast level material with stuff that’s been shot by shows with beautiful photography, with graphic animation, so you’re combining six or seven different types of imagery to create a scene and emotional beats. That’s an amazing process to be a part of.

Ian Bonhôte: And a lot of people get emotionally involved within the story [because] it fulfilled them visually — that’s why they want to go into the cinema. If I had any message for any potential audience [for this film], it’s a documentary but it needs to be experienced on the big screen because the music from Michael Nyman, as well as the visual richness that Peter was going through, the best way to experience it is with a big audience and on the big screen.

Ian Bonhôte: [Michael] yes, but I don’t think we had worked out which track when.

Peter Ettedgui: Even from the earliest conversations, we knew that there had been this kind of relationship between McQueen and Nyman and that McQueen loved Nyman’s work, so it’d had been a no brainer. But we then had to convince Michael Nyman to come onboard and discuss [whether] it was going to be an original score or made up from his catalog. Ultimately, we decided to go from catalog partly because of time, but also partly because Michael’s music is so diverse. There are different periods of Michael’s music, just as there are different periods of McQueen’s work and we felt we could use the two to echo each other and build a sonic storytelling, so it starts from a bigger, more brutal driving rhythms of [his work with Peter] Greenaway and then by the end of the film, Michael’s much more tender solo piano pieces, so we tried to use this amazing catalog to help us with the storytelling.

Ian Bonhôte: We were given 25 hours of music and within the catalog we could actually find every single musical beat as well as emotional beat we wanted to express for the audience.

Peter Ettedgui: One of the great things about having this 25 hour catalog is of course, you’ve got the cues that are so redolent like those early Peter Greenaway cues that feel so much of the ‘80s and ‘90s when McQueen was beginning, but then there was this incredible library of music that very few people have heard unless their Michael Nyman fans — music he’d written for string quartets or for orchestra or concertos, so it was remarkable to be able to thread some of that music in with some of the more well-known things. Michael’s thrilled with it, by the way.

Ian Bonhôte: Yeah, he decided to release an album of the movie and that’s a decision from him. A tiny little story is when we first met Michael, he brought a piece of music that he had actually recorded for Lee for one of his shows, but at the last second, Lee decided to use a track from “Schindler’s List” instead, so no one had ever heard this track called “Saraband.” He played it to us and we loved it and we used it where it was supposed to go, which was a Kate Moss hologram for the Alexander McQueen show “Widows of Culloden.” That track was created for Alexander McQueen, not for Peter and I making an Alexander McQueen movie, so it felt that we were restoring something the audience could’ve seen and experienced 10 or 15 years ago, but now they experience it within the movie.

“McQueen” opens on July 20th in Los Angeles at the Arclight Hollywood and the Landmark and New York at the Angelika Film Center and the Landmark at 57 West.