As much as Pablo Escobar had been wanted by the authorities before his ignominious death in 1993 trying to evade the reach of the law one more time, the drug kingpin has been even more wanted by Hollywood, with countless filmmakers seeking the chance to make a biopic of the man who built an empire worth nearly $30 billion during the 1980s. The irresistible story of Escobar working his way up from stolen cars and selling cigarettes on the streets to pumping millions of kilos of cocaine into the United States grown in his native Colombia once inspired a race against the clock between Oliver Stone and Joe Carnahan, battling over the services of Edgar Ramirez to play Escobar in rival projects in the late 2000s, only for both to fail to start production while Benicio Del Toro finally was able to play the role in Andrea di Stefano’s 2014 drama “Escobar: Paradise Lost,” but largely eschewed the drug lord’s heyday by joining him when he was on the run.

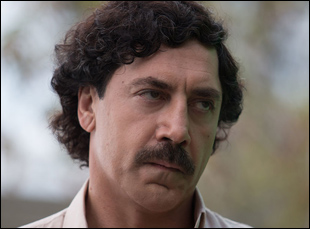

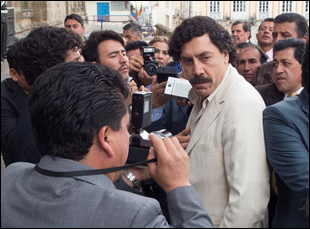

For that reason and others, it is rather remarkable to now have “Loving Pablo,” a bold, brash evocation of Escobar’s rise and fall in full, an unbelievable tale that comes from an unexpected source — writer/director Fernando León de Aranoa, a filmmaker known for quiet character studies such as the Javier Bardem breakthrough “Mondays in the Sun” and the Goya Award-winning 2005 prostitution drama “Princesas.” Although anyone bringing Escobar’s sprawling story to the screen would have their work cut out for them, particularly with a central character who had to take himself so seriously when no one else would, León de Aranoa’s reunion with Bardem takes an interesting tact in bringing his larger-than-life exploits down to earth — most of the time, given the number of the drug dealer’s schemes involving planes — by transferring the role of narrator to Virginia Vallejo (Penélope Cruz), a TV journalist who became Escobar’s lover. While the flamboyant Virginia seems like a perfect match for Escobar at the height of his powers, putting on one dress after another that would attract as many eyes as the illegal activities her boyfriend would flaunt with impunity, the world actually grows smaller and smaller as paranoia about when the law will finally catch up with Pablo takes hold, especially when a DEA agent (Peter Sarsgaard) eager to take him down starts making entreaties towards her.

When Virginia’s emotions start to change toward Escobar, “Loving Pablo” begins to take a different shape as well, starting out as a breezy, garish trip through the good times where it didn’t matter where the money was coming from so long as Escobar and crew were having fun to a more claustrophobic thriller that takes into consideration the victims of his many crimes and life inside the prison he inadvertently built for himself. Shortly before the film is released stateside after premiering last year at the Venice and Toronto Film Festivals, León de Aranoa spoke about overcoming both the daunting technical and dramatic issues that may have made the story difficult to translate to the screen before as well as filming some of “Loving Pablo”’s most harrowing sequences and working with real-life couple Cruz and Bardem.

You’re right, and I don’t know, because I wasn’t involved in the production of those films, but maybe the events were too close and there was still not enough perspective to do it [justice]. It was actually 13 years ago that Javier and I started talking about doing this film and we didn’t try very hard, but we were always talking and four years ago, we started saying, “We should try. Let’s write something and let’s see if it’s strong enough to have people involved in the production.” Then I start reading and reading about Pablo Escobar and what happened in the ‘80s in Colombia and we wrote the script and managed to do it.

With over a decade to cover, what became most important to you to portray about Escobar’s life?

That was the toughest part for me. The choice of having Virginia be the narrator of the film helped a lot because we never wanted to do a POV of Pablo Escobar in order to tell the whole thing, even if the whole thing is very, very interesting, and the film [is divided into] three different stages for me, linked to the same idea of Pablo Escobar trying to get some respect and acknowledgement from people. This was something I read about and I think was the most interesting psychological approach to the character — because of his humble origins, he was trying to have this recognition and at first, he tried through economic power, so he became one of the richest guys in the world, but he still wasn’t respected because they knew he wasn’t part of the oligarchy in Colombia, so he tried a second stage and he ran for Congress and he got a seat in the chamber, but still he didn’t get respect because [how he earned his wealth] and they [ran] him out of the Congress and then he tried through the military power. And this is something that he says to his son in the film, “Son, you need to get recognition. If you can’t get it, you have to get their respect and if you don’t get them to respect you, then get them to fear you,” so these three stages [became] the spine of the film.

We found her voice was unique for several reasons. One was because she is a woman and such strong female characters are not that usual to find in these kind of environments of trafficking. They are usually men, both in films and in real life, so to have this strong female character in the heart of this situation was very interesting, but she’s also very special. She was a [high] society woman with a lot of social skills that Pablo did not have and she actually became a kind of “Pygmalion”[-esque figure] for him, a teacher [who could show him how] to do interviews [with the press and the public]. She was educating him, and I also loved this idea of her being a journalist, giving this big frame of events in Colombia, which is a very important part of the film to me, but also because of her relationship with Pablo, she could give us the closeup on him. We have these five or seven sequences in the film where it’s just them in a restaurant or a room like [where we’re sitting now] and those sequences are where you can actually tell who Pablo is – how he performs with another person, a person he loves and he’s very often cruel [to], so Virginia gave us a chance to do two things – the big frame and the closeup on Pablo’s psychology.

Did Javier and Penelope come as a package deal or did Penelope join later since you were working with Javier initially?

In the very beginning when we were just thinking about doing a film about Pablo Escobar, I was thinking of Javier, but then as soon as we found Virginia as the right point of view for Pablo Escobar’s history, Penelope appeared to me as like the perfect actress to play that role, so when we went back to work four years ago when we made the decision it was for us to do together.

Because we are telling a 10-12 years of the history of Colombia, that’s pretty ambitious and I always thought of the film [as being] pretty intense, so we made this decision to start filming in the first quarter of the film, having this world which was glamorous [with] a lot of money and they had this [palatial mansion] with the animals and the huge parties and the planes, always [with] long shots showing all the glamour, but somehow fake – because behind all that glamour, it was the drug trafficking. It was built on rotten roots, so in the beginning, the color and the lights are much more brilliant, even Virginia, with her [extravagant] dresses, then step by step it actually becomes, not necessarily darker, but more real and it’s like the film is stretching and stretching and stretching until the end, this guy is in a small place like [the room we’re sitting in], waiting for the cops to come and he’s cornered with just one person beside him. The end is much more realistic in terms of storytelling and the kinds of lenses that we use, the kinds of shots that we made, it’s like reality is there, but at the beginning [it’s] somewhat fake and the real thing is what you can find in the last third of the film – all the pain and the suffering.

What’s it like to capture something so surreal as landing a plane, carrying drugs from Colombia to Miami, on the freeway?

That comes from reality, as almost everything does in the film, and sometimes, especially in order to tell this big [story] in two hours, you need to reinvent things somehow, but you always use real materials and real situations. This happened actually [with] the people previous to Pablo Escobar who used to land planes that were maybe a bit smaller on the highways of Florida and I couldn’t believe it when I was doing research. It’s like the wild west, right? It was the first years of the business and it was crazy, so I always wanted to have that sequence in the film. It was completely wild and it was challenging to film this sequence because we didn’t film on a highway, of course, because that’s not possible, so we did it the other way around – we filmed on a landing strip, so we placed all the signs of the highway and all the cars along a landing strip, so the plane could land in this place.

Once more, this from research. They used to do these pretty easy things, like having these birds in order to spoil the helicopters. This was a moment where [Escobar and his crew] were actually hidden in the middle of the jungle because they were really cornered, so they used to put these ropes between the trees, so the helicopters couldn’t land because they will crash and these are cheap ideas, but very effective. They had this privileged mind for crime. I actually read something that in the beginning of his criminal career, Pablo Escobar used to steal things from shops [with friends when] they were 15 years old, and he painted one side of the bike red and the other side white, so when they were running away, [different] people would say, “It was a white bike.” “No, no, it was red,” It’d create confusion. [This scene with the birds] we made the decision of filming this one in a long shot in order to bring the feeling of being there in the middle of the jungle and suddenly having this strong attack from a helicopter, and he manages to run away as he did very often.

Every successive film of yours has seemed to be larger in scale. Have you actually made that a goal?

The next one is going to be like “Fall of the Roman Empire”! [laughs] I don’t think so. No, it’s not part of a plan. Actually, the previous film “A Perfect Day,” with Benicio Del Toro, it’s actually pretty small. You’re in the middle of a war, but a lot of it is about these guys trying to drag a corpse out of a well, so it’s a pretty small and surrealistic kind of story. This one was much more bigger and ambitious because of what Pablo Escobar did. And who knows? At this moment, I’m writing something a character-driven story to be filmed in Spanish, but if I I fall in love with some other film that’s bigger, I will do it. This is a blessing – the chance to do a lot of different kind of films because you learn a lot. The best experiences are when you finish and you feel like you learn something and this is [the case] for “Loving Pablo.” I’m pretty proud and happy that I did it, but the next is probably a much smaller film.

“Loving Pablo” opens on October 5th at the Sunset 5 in Los Angeles, the Village East in New York and on VOD and on Amazon and iTunes.