Fernanda Faya couldn’t help but wonder why there was nowhere near as many old photographs or footage of her aunt Neirud as there was of her grandmother Nely, the two having become joined at the hip when the latter was a circus performer and the former joined her on the road during the 1950s and ‘60s when female wrestling was illegal in their native Brazil, yet a loophole made it far less frowned upon under the big top where it was potentially a bigger attraction than any trapeze artist or fire-swallower could be. With her broad shoulders and burly demeanor, Neirud became a star at the circus, but Nely was the one whose time there was preserved with Faya’s father Edgard holding onto memorabilia and newspaper clippings that announced when the circus was coming to town and by the time Faya was old enough to start asking questions, Neirud and Nely were both well past remembering, as much because they may have been foggy at their age as there being little point in resurfacing such things.

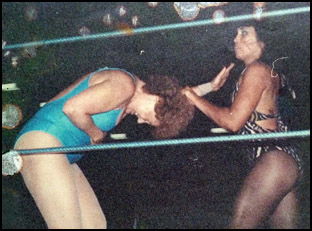

In “Neirud,” Faya begins to tug at a string that the woman she knew as her kindly aunt left behind, a lone clip that she had filmed when speaking about his she ran off to the circus at 12, her darker skin standing out from the the rest of the family she lived with in Brazil’s whitest region of Rio Grande de Sul and the filmmaker comes to tell a story of someone who never found the right fit, ultimately including the potential to be squeezed out of history, even though she undoubtedly left a mark on so many. Her opponents in the ring would certainly be able to testify to this, but Faya is able to show the deeper impression she made as she takes what’s within her father’s collection and memory and begins to close the gaps with her own research of a push towards cultural conservatism in Brazil that led to many hiding their lives from public view. It’s hard not to think of present day Brazil where evangelism has refashioned the entire political system in the country as one watches Neirud become a disappearing act, and Faya is able to connect the past to the present and brings to light the usually unseen arbiters of what becomes important.

After premiering earlier this year in her family’s home country at the Curitiba Film Festival, “Neirud” is set to make waves when it premieres this weekend at DOC NYC in the director’s adopted hometown of New York and she spoke about how in setting out to make a film about her family, Neirud rose to the surface, finding a low-tech yet effective cinematic tool to give an extra sense of intimacy and connecting with one of Neirud’s adversaries in the ring.

It’s been 10 years, and it’s a film that started [with] the initial idea of documenting my family because coming from the circus, I grew up thinking that it was unique and interesting and I felt attracted to all of those stories. [This was] when I was in film school, and I spent a lot of time fundraising and grant writing, but this was actually good because in the end, with time I also matured as a person and was able to also detach from my dad’s narratives and be a little bit more suspicious about the story that was hiding behind all the beautiful stories about circuses. Finally in 2017, we got a grant to make a short film, but with the amount of footage and archival we had, we easily realized that it wasn’t going to be a short and in the editing, we figured out what was the film about and we committed to telling a story about Neirud. She passed away in 2011, way before I decided to make a film about her, but back in 2011, I had my first digital camera that I was carrying around, so I was able to film her a little bit when I was just documenting stories about the family and she was able to tell me one or two things and shortly after she passed away.

Was filming generally a part of your family history? I was intrigued with the amount of material you had on film and with the circus background, I thought it was natural that someone would want to capture it.

Filming was not at all part of the family history, especially because in Brazil, it’s very uncommon for people to have video cameras around. It’s more for privileged families, especially in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s. It was a very expensive item, and it wasn’t something that they were doing in my family, but my dad did collect a lot of archival stuff, related to his family’s circuses and history, so he had posters and newspapers that mentioned my grandmother and the family’s circuses. He also had kept the tickets that you buy to go see a circus show, the vintage ones from the ’60s.

You find a pretty novel way to make those artifacts cinematic with the use of a magnifying glass. How did you end up with that approach?

Part of figuring out what the story was involved understanding also who was I supposed to be in the film? Because for a long period of time, I was in front of the camera as a more present character, but not really doing anything, and the moment we realized that the story should be about Neirud, it also became clear for us that my character in the film should be this person who’s investigating, someone who’s trying to find pieces of information and documents to be able to reconstruct or piece together her stories. It was about that moment when we realized that I was, that this is my role, right? As the character in the film that we thought about the magnifying lens [could be] a way to also provide an immersion in those documents because there’s not a lot of photographs of Neirud. Only one or two things that I’m able to find become rare in the film because we’d only have one or two images of her and that’s it, so the magnifying lens became both a tool of this investigator who’s trying to find clues, but also visually and aesthetically, it allows the viewer to become closer to those images and feel their texture, which was very important for us because in general, I think this film is very handmade, and the magnifying lens brings up this texture and provides this immersion that we thought was really nice.

When we decided that we wanted to tell a story that was chronological, it was clear to us that [Neirud] was doing something outside of the norm, confronting society’s expectations and she was a complete outsider, so her [mere] existence was a statement of how to exist outside of the norm, and then you have to be able to see what that norm is. Patriarchy is very vague, but the archival materials [became] a way for us to show what were the expectations that society had about women in the ‘50s — for example, you see like an archival footage of women doing groceries, carrying babies around and taking the train, and it’s a certain image of how women should look that was so different from what Neirud was, so I thought we had to bring in these archival materials to create this contrast, and to make it explicit that this is the standard of the time — to see those very curvy, feminine “women,” there’s a pageant scene that we were able to find. That was the norm, and Neirud [stood] in contrast to what was expected, and it was very interesting to see the archival from that time and think, “Oh my God, it feels like a long time ago on one hand, but on the other, laws that allowed women to get divorced are [only] from the ‘70s in Brazil, so it’s not a long time ago. That made us realize how much did not change, and it became even more important and urgent to tell [Neirud’s] story because if she was doing that in the ‘50s and ‘60s, it’s encouraging to think that we have to keep confronting those norms and find ways to exist that are not following this pattern and expectation that is very patriarchal.

Rita is someone that I met in the process of investigating Neirud’s story because the first stories about Neirud that I heard came from my dad, and he would tell me certain things about her that he had access to, but my dad’s family is very small and everyone [else] had passed away, to be honest. So when I started asking questions about Neirud, there weren’t many people around who had known her and I started broadening my investigation and reaching out to other female wrestlers or the parents or relatives of other wrestlers because she was part of the scene and I thought, someone worked with her in the past and if I’m able to find those other women, maybe they will be able to tell me something about Neirud that I don’t know. But because she was such a pioneer, [wrestling] in the ‘50s and ‘60s, all of the wrestlers passed away and I would hear one or two stories from their children.

But finally someone told me that there is one wrestler from that time who is alive and she knew Neirud, so it was really like a true investigation. Rita and I would never meet [in person]. She lives in the South of Brazil, on the border with Argentina, and she’s [around] 95 at this point. But I was able to find her daughter’s phone number and she knew my grandmother, so she knew who Neirud was because families who are in the circus know each other by last name, so I explained that I was doing this project and I knew [Rita] was part of the same troupe [as Neirud] and I wanted to hear those stories. And Rita sent me voice notes because she’s not even able to talk on the phone because she’s very old — her daughter would be like a mediator, and I would ask something that [she] would ask Rita and record her answer and [she] send it to me over WhatsApp. And she [ended up] playing such an important role because she was the only one who could actually tell me things that happened at that time. Everything that she said was really precious and the way she refers to Neirud is so powerful. She [calls] Neirud the ring’s sacred monster, and listening to that for the first time, [I thought] “Wow, that’s the dimension Neirud had within the wrestling community.” Everyone had a lot of adoration for her, but also respect because she was one of the pioneers, so hearing that from Rita meant so much to me and I had my access to that universe of wrestling within that troop in that time period.

You’ve been carrying this with you for some time. What’s it like starting to bring it out into the world?

We had an incredible world premiere at Curitiba in Brazil, which I’m very grateful for and obviously my main concern was how are people going to perceive this story and are they going to be able to see all the layers and subtleties that I put into the film, but we won best film and best editing right off the bat [which was] a validation for me and it made me feel a little bit more calm that the values that I see in the film are also being recognized by who’s watching it. And then premiering in New York for an American audience, I almost feel like I have the same exact expectations and fears that I had before the film world premiered [in Brazil] because it’s a different culture, so I’m very curious and excited to see how people are going to react. I’m so happy to be premiering in New York [since] I’ve been living here for eight years and having the opportunity to show the film with my community here, with my students who are going to come and my community of friends and family that I have here just makes me feel very happy. I’m so excited, and I think that everyone has any filmmaker showing the film for the first or second time or even the 10th time, will be worried at some point, just [from] the sense of responsibility that you’re telling a story and [you wonder] what people are going to get from the story is what you intended them to get. But I know this is not in my control anymore and [I hope] people going to be able to see the things that I wanted to show and the questions that I wanted to raise.

“Neirud” will screen at DOC NYC on November 11th at 8:30 pm at Village East and will be available to stream virtually from November 12th through November 26th.