Around the holidays, it could often seem like the only place busier than Santa’s workshop was DuArt. During the 1980s and ’90s, a great many of the gifts that would soon be unveiled at Sundance were processed at the film and TV lab in New York where technicians worked feverishly to make sure all of the features would make their premieres, not letting an unforgiving timeline get in the way of their typical high standards when it came to color correction or reframing shots that might not work as well when the lower-budget projects shot on 16mm were blown up for 35mm projection, the general standard amongst festivals for public presentation.

“It was just maddening,” recalled Bob Mastronardi, who started out as a customer service supervisor at the lab in 1980. “When DuArt became this hub for independent filmmakers, we were always slammed up against the wall at festival time, whether it was Sundance or Toronto or Berlin, and I always used to think there’s no way we’re going to get all this work out the door, but we did. No one ever missed a screening.”

And as Domenic Rom, who joined Mastronardi at DuArt in ’84 as a colorist, adds if there was any concern about the quality of the work under such tight deadlines, they were less likely to come from the clients than from his boss Irwin Young.

“It was nuts. We were working up until the last second every day and it was worse for the lab than it was for the video department because in those days, everything was being shown on film,” says Rom. “Irwin wasn’t happy with the blow up of ‘The Brothers McMullen’ because the film stock they had shot on was older and grainy and [Irwin] kept remaking it and remaking it at no charge until he was as happy as he could be with it and he got on a plane with the film cans and flew out to Sundance and got to the theater before the first screening. That’s the kind of service we did in those days.”

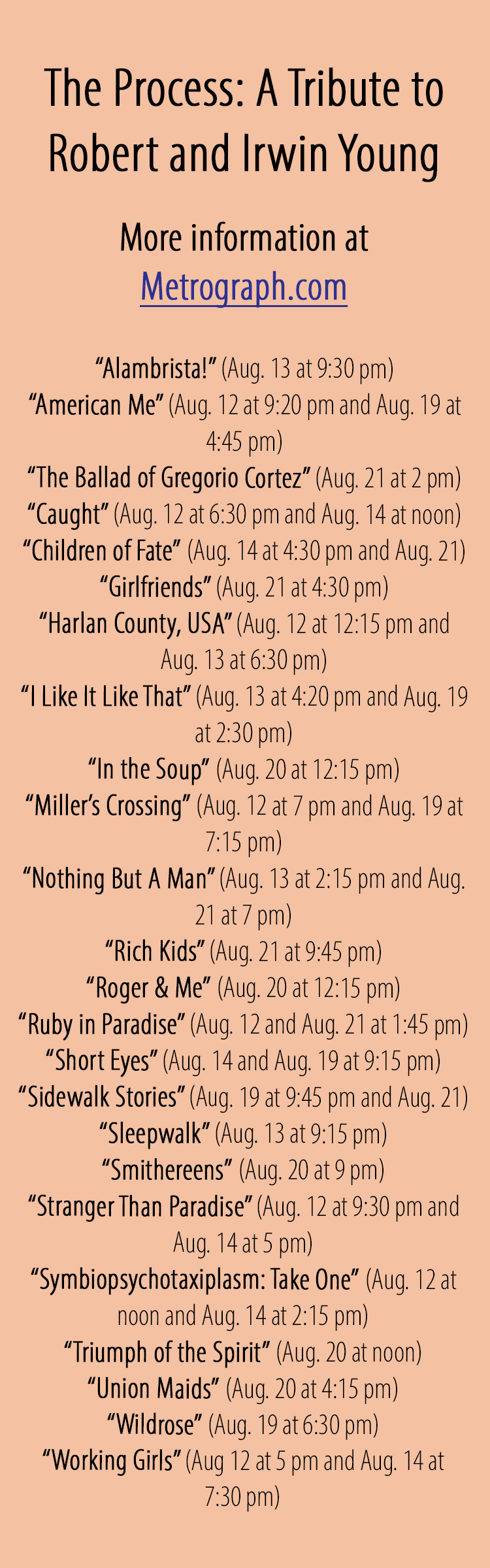

If it was a race to deliver the goods, there was at least a growing awareness amongst DuArt’s staff that their work would stand the test of time, going well beyond the usual role of a film lab to bring many of the most beloved films of the American independent film movement in the 1980s and ‘90s to the screen. Their contribution to film history is being celebrated this month with the series “The Process: A Tribute to Irwin and Robert Young,” a mere 1 train ride away from their old offices at the Metrograph in New York. Honoring the sons of Al Young, who founded DuArt in 1922 after learning to develop film in its birthplace of Fort Lee, New Jersey, the retrospective offers a look back at the company’s output under Irwin’s purview and the influence of his brother Robert, who helped pave the way for an entire strand of American dramas mixing documentary and dramatic techniques, first as a co-writer with director Michael Roemer on 1964’s interracial romance “Nothing But a Man,” and as a director himself on the groundbreaking “Alambrista!” and “The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez,” in which he brought audiences into looking at issues around the U.S./Mexico border.

At DuArt, Irwin was well-positioned to make a difference – and had incentive to when all the major studios based in Los Angeles were inclined to work with local titans such as Deluxe and Technicolor. With a steady business from corporate clientele outside the world of film, DuArt could afford to offer payment flexibility and more radically, a fee based on the length of footage that could be easily incorporated into a film’s budget rather than an hourly rate that presented the ever-looming fear of charging for overtime. Yet Irwin’s creativity when it came to the financials was indicative of the overall ingenuity that would attract filmmakers such as Michael Moore (“Roger and Me”) and Jim Jarmusch (“Stranger Than Paradise”) to the lab early in their careers.

“As an engineer, he was infinitely curious,” says Tim Spitzer, who started out at DuArt in 1980. “He was one of the first people to really understand the relationship of working with video and supported the idea of having a video operation as well as a film operation.”

Spitzer may have been initially disappointed when he was first assigned to split time between the film and video departments at DuArt instead of strictly being in the optical printing department as he had hoped, but it put him squarely in the middle of a filmmaking revolution as Young and the staff at DuArt constantly looked to facilitate the process amidst technological headwinds. The lab had an illustrious history of innovation from the earliest days of film to its maturation as a medium, being the first to process a 35mm color print due to a close relationship with Eastman Kodak, but when few regarded 16mm as a comparable alternative, Young invested heavily in developing the machinery that could process it when other labs dismissed it. As the appeal of 16mm and Super 16 grew to network news crews and independent filmmakers for its cheaper price point and more intimate feel, DuArt had a business all to itself. Still, Irwin would look beyond celluloid for anything that could improve the end product and make the process more efficient for filmmakers.

“I can remember so many times where we would be in meetings and he would be twirling his hair, thinking what’s next?” says Mastronardi. “He was always ready to be considered part of whatever new technology was out there and if they didn’t have it and he thought it was necessary, he’d try and invent it. In that sense, [DuArt] wasn’t just a laboratory production environment, it was like a science lab.”

Along with president Robert Smith and optical printing chief David Leitner, Young had been far quicker to embrace computer technology than most in the field. DuArt became one of the first labs to import a Rank Cintel Telecine from England that could transfer film to video and they made waves throughout the industry with the advent of frame count cueing, a process that enabled the optical printer to sense when timing lights would change with the assistance of a computer, speeding up the process and eliminating the risk of physically damaging the negative when the process previously involved cutting notches on the side of the celluloid to mark shifts and could dirty up a print.

The advancement would lead to an Academy Award, but many of DuArt’s less heralded achievements were equally as impactful on the sets of independent productions where every second saved could be the difference between art and catastrophe. At a time when dailies would be rushed from the set to a lab and could take days to process, DuArt could promise them overnight and built an operation where film and video were given equal consideration, eventually coming to offer even more instant results when transferring film dailies to video accompanied by detailed daily timing reports, allowing cinematographers to get a gauge on what the exposure was and the condition of the film they were shooting, even in spite of the idiosyncrasies that might result from the transfer. Never satisfied, Young would continually insist on tinkering and even many of the ideas that didn’t work at the time now seem prophetic.

“Way, way back when DuArt actually tried relaying the image from where the source film was — the raw stock — through a fiberoptic bundle or cable, they actually had a patent on that,” says Spitzer, of the pre-Internet experimentation. “It didn’t work out terribly well, so the patent was let to expire, but if you think that they had the patent on relaying images over fiber, [DuArt] would be multi-trillionaires at this point.”

Even if DuArt was a little too ahead of its time in some respects, the lab did pretty well for itself.

“You never knew who you were going to get on the elevator with,” recalls Rom. “It could be Milos Forman, it could be Spike Lee, it could be Sylvester Stallone, it could be Albert Maysles or Barbara Kopple, you were working with these people, incredibly creative and they all felt at home there because what Irwin was able to create in that building was a sense of family and we’re going to take care of you.”

“It was just an extraordinary experience to take a story that was untold and bring it out onto a much wider stage,” says Schulberg, who would go onto create the Independent Filmmaker Project, first a market and then a full-fledged nonprofit organization now known as The Gotham that would help build a viable commercial pipeline for indie cinema. “As a result of the Camera d’Or award, George Pilzer, my mentor in terms of international sales and marketing, allowed me to take over the licensing of this film and we were able to make deals with wonderful arthouse distributors all over Europe and all over the world… I then got to know them and was able to invite them the following year to come to New York to show them that yes, it wasn’t just one or two or three films.”

If Young appeared to be giving the special treatment to “Alambrista!” based on family ties, you could see just how large he believed his family to be when DuArt regularly sponsored lavish parties at festivals, intended to give filmmakers arriving for the debuts of their first films a real sense of accomplishment and his insistence that everything that DuArt would give everyone who came into the building world class treatment extended from the great filmmakers of the day to NYU students bringing in their thesis films for processing, helping the latter become the former.

“It was interesting to watch and to be part of because we went from dealing with unknowns – when we worked with Roger [Deakins], he was unknown and because of his work, other cinematographers would say to each other, ‘Go to this lab. They really take care of what you need and they protect you,’” says Mastronardi. “Gordon Willis did some films with us and he was happy and very pleased with our work and if you please Gordon Willis, who was a notorious curmudgeon and a stickler for detail, that word gets around.”

As renowned as DuArt was in the 16mm realm, the lab grew to have a robust 35mm operation to compete with the likes of Deluxe and Technicolor, under the leadership of Don Donigi, who instilled the same exacting standards in his staff as Young would hold him to and ultimately be inducted into the American Society of Cinematographers, exemplifying the admiration that many directors of photography had for him. Eventually, digital video would lead to downsizing at DuArt where technicians could still fine-tune picture to the highest standards, but the need for film processing was greatly reduced and in 2010, DuArt would shut down the film lab entirely, their last film being Schulberg’s restoration of the documentary her father directed, “Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today,” commissioned by famed documentarian Pare Lorentz for the U.S. Department of War. She, David Leitner and Irwin’s nephew Andrew Young had the foresight to film an interview with Irwin that day, but while it was an undoubtedly sad occasion, Irwin wasn’t one to wallow for too long, knowing he still had work ahead of him when there were so many orphaned prints still sitting in the lab, some perhaps being the only copy of the film left without its producers knowing where it was.

After every other way he had done right by his filmmakers, Young and his daughter Linda, who would take over day-to-day operations as CEO at DuArt in 2009, helped IndieCollect return these films to many of the people that had made them and could afford to house them, from Spike Lee to the Coen brothers, and placed as many others in safe keeping at repositories ranging from the Academy Film Archive to the UCLA Film and TV Archive. (Among them was “Cane River,” the delightful long-lost drama from first-time director Horace Jenkins, rescued by Academy Film Archive curator Ed Carter, that offered a rare glimpse of Louisiana creole country from 1983, and restored to its original luster and its pioneering place in history for an Oscilloscope release in 2020.) Irwin would pass away earlier in January of this year, just months after DuArt would shut down as a media services company in August of 2021 after 100 years of serving filmmakers, though naturally the decision was made to keep the building, with its plum position on Columbus Circle, open to those working in creative industries.

Although its employees made sure not to leave their fingerprints on any negatives, those of DuArt can still be seen all over the industry. With films such as Susan Seidelman’s “Smithereens,” William Greaves’ “Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One,” Claudia Weill’s “Girlfriends” and Darnell Martin’s “I Like It Like That” now recognized for the groundbreaking work that they always were (and will be playing at the Metrograph in the weeks ahead with their filmmakers in tow) , Young’s investment in the creative community has paid off in ways that continue to reveal themselves over time, as well as those that worked at DuArt, spread out across the post-production community in New York and beyond, who haven’t forgotten his belief that as much of a science there was to their lab work, tending to filmmakers was an art. Young’s all-too-rare mix of the head and the heart was on full display when Rom, inspired by his example, had hoped to move into an administrative position at DuArt and experienced how passionate and practical he was when it came to wanting the best for those around him, even when those impulses were at odds with one another.

“I had spoken to Bob Smith about it and I had Bob’s support and Irwin walks in and he says to me, “I hear you want to be in management.” And I said, ‘Yessir, I do.” And he said, ‘I’m going to tell you something — you’re an asshole,’” Rom recalls with a laugh now. “He says to me, ‘You could make a lot more money being a colorist — [and] he was right. I could’ve made a hell of a lot more money, but I was more excited by what he did and the relationship he had with the filmmakers — but [he said] ‘If you want to move into management, I think it might be a good move for you. You have my support.” And the next thing you know, a couple years later I’m running the company.”

Rom would become the executive vice president at DuArt and has since found his way to Goldcrest New York, a post house now held in as high regard as DuArt once was, where he is managing director and continues to strive to serve filmmakers as Irwin Young did.

“There’s nobody that does that anymore, not the support like he gave,” said Rom. “That was what was amazing about DuArt was the care and the attention you got from the owner of the company.”