While his skill at getting uncommonly intimate with his subjects has long been the stuff of legend, it becomes apparent when you meet D.A. Pennebaker that his humility has been equally crucial in allowing people, often very high profile under great duress, to reveal themselves before his lens. Now 90, though you wouldn’t know this from his enthusiasm, Pennebaker is eager to give his partner in life and film, Chris Hegedus, with whom he’s been collaborating since the 1970s, all the credit for shooting their latest movie “Unlocking the Cage” and is equally generous in surveying all the filmmakers whose approach to capturing the world around them was so profoundly impacted by his development of the first synchronized 16mm camera that captured sound and picture at once with Ricky Leacock and what he did with that camera on such films as “Monterey Pop,” the ’92 Clinton campaign doc “The War Room,” and more recently, “Kings of Pastry,” suggesting that he is now no different that the thousands uploading what they shoot onto YouTube every day. (“You know, that’s where most of our stuff is too,” he’s quick to confide.)

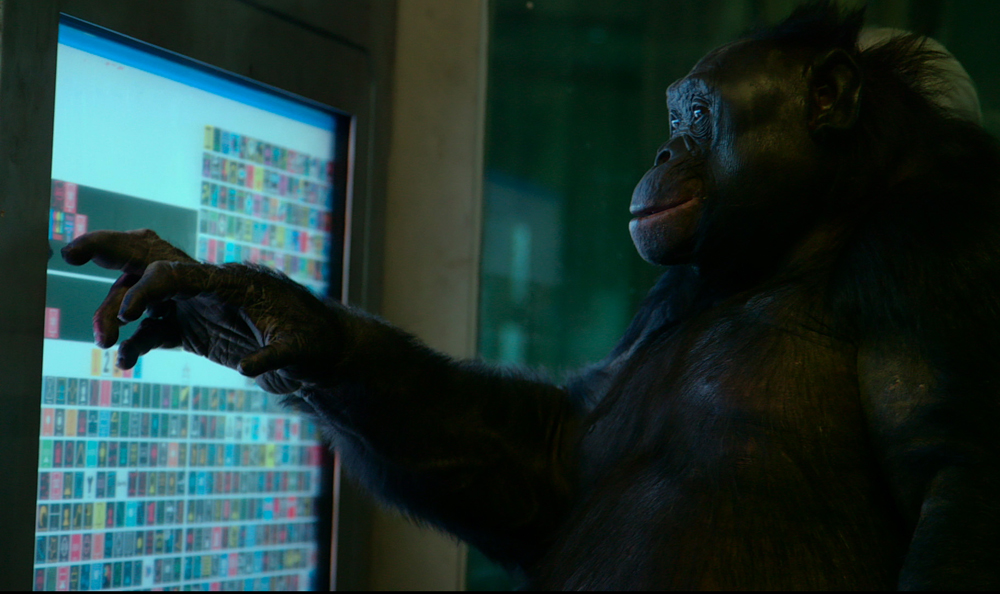

Still, it’s evident from the first moments of “Unlocking the Cage” that you’re in the hands of masters of the form in Pennebaker and Hegedus, who follow lawyer Steven M. Wise on his quest to give animals the same legal standing and rights as humans do. After founding the Nonhuman Rights Project in 2007 with the aim of finding cases that could set precedent, Wise is finally preparing for his day in court with a petition for a writ of habeas corpus in 2013 on behalf of four chimpanzees — Tommy, Kiko, Hercules and Leo — held in captivity in the state of New York, aiming to release them into the care of a sanctuary and have them recognized legally as autonomous, self-determining beings under the law. It’s an uphill climb to say the least, but a righteous one as the film demonstrates, quietly observing the visits Weiss and his staff make to the unnatural homes of the chimpanzees, where many are overcome with loneliness, a stark contrast to the brilliance they’re shown having in earlier years when they were asked to star in films where they’d do karate or drive cars.

While the film builds a case of its own for the animals, it becomes a fascinating chronicle of a legal process geared not necessarily towards winning some big, sweeping victory but the small, incremental changes to set up such a sea change as Weiss suffers through mock trials to toughen his position, finds small glimmers of hope in the decisions of judges who have rejected his claims and keeps fighting on. It is the rare film to be executive produced by HBO Documentary Films to see the big screen first, a forum particularly suited for Weiss’ epic court battle and as the film is making its way across the country theatrically, Pennebaker spoke about how he and Hegedus made “Unlocking the Cage,” the inspiration of their own beloved furry companion, filming in courtrooms and how they get so close to their subjects.

Yeah, pretty much, like [if we] were a painter, we wouldn’t sit down and say “what do we paint today?” When I worked at Life Magazine, researchers would pass us sheets around telling us what what was going on in the world, and you could pick up a subject from those sheets and decide what to do, but [as filmmakers], that’s an expensive operation to deal with, so in a sense, somebody comes to us and tells us of a story they know about and if it’s interesting to us, we figure out if we can do it, if we can raise the money and have the time. In this case [of “Unlocking the Cage”], somebody we knew very well told us about Steve [Weiss] and when we saw what he was doing, it was such an adventure because you don’t go and decide to change common law idly. He knew enough about it to know the risks for himself to try to do it, so watching him try to do it seemed like a really good idea for a film. It was also the beginning [of his process] and from our point of view, documentaries should always start at the beginning, if they can, and follow the things so you don’t have to tell anybody what happened — you can see what happened.

And this coincided with having a dog around the house for the first time.

We had a dog that we dearly loved that used to come to work with us and sit under the editing table as we worked — he wouldn’t have imagined not going to work with us, that’s what his life was. He died because he got old and he was partly an Akita — their rear ends are not very well designed unfortunately, so we had to put him down. He just couldn’t survive and we were still in sorrow, thinking about it, so when this film came along it struck us that this was an animal film and we would like to do an animal film.

You say Chris shot it, but how do you and Chris collaborate on a film like this?

We go out together to see what’s going on, to see the people involved. We both talk to them, but she films it. In the old days, you had to have a couple because one person did the sound with a Nagra [recorder], and the other person had the camera. Now, the sound is part of the camera, so it no longer needs an additional person, but I’m there because we just always do these together. If we want to decide whether to do a certain aspect [of filming], we decide it together.

I’ve actually heard you say you don’t do any research for your films before you start shooting.

We never do. The film is the research.

Since there is some archival footage in “Unlocking the Cage,” at what point do you start bringing that in?

Just when it occurs to you. You’re making the thing all the time — that’s all you’re thinking about — and once you start to film it, you don’t shoot everything that happens because you don’t want to be perceived as [being] only interested in making your film. You really want to share the film with the person you’re making it about. [For “Unlocking the Cage,”] it’s [Steve’s] film too because it’s his life we’ve expropriated in a way. Many of these films, like in “The War Room,” [with] James [Carville] and George [Stephanopoulos], we showed it to them, and nobody else, [because] if there’s something in there we haven’t got right, we’ll try to correct it. We don’t want you to edit the film, but we want to share the film with them because it is their film too, and they want to feel that way.

“Unlocking the Cage” has been described as your first activist film, which I’m not sure I agree with, but did knowing there was a cause attached affect your approach?

I don’t know what that means exactly, either. Basically, we’re interested in a guy who’s trying to climb an incredible mountain. For all we know, he can’t make it — it’s impossible — and the odds are against him, but he looks like a person who wasn’t going to give up. The purpose of the climb suited us [because] we like the idea of helping an animal. [The chimpanzee] isn’t a pet, it’s an animal that’s enslaved its whole life, which is 65 or 70 years, just because you can’t leave it out of a cage and you’ve enslaved a creature that’s very much like a person, which seemed to us like something worth rectifying and to somebody that’s interested, to see how they do it. Our purpose was to follow Steve, not to save animals [since] we can’t — we don’t know how to do it, but we could follow somebody who maybe does. Many people will feel it’s about chimpanzees, which it’s also about, but it’s about Steve. If he wanted to save elephants, we would’ve done the same thing.

He had to send her up because he was doing something else and couldn’t do it. They were planning on initiating a suit almost immediately, but they just wanted to be sure [Merlin] was okay. When she got there and he wasn’t there, then she had to tell Steve and they had to go and look for some other chimp [because] at the beginning, they just thought they’d just get one chimp and that would be the film. Instead, they were scouring New York State for chimps, and a lot of them were dying because keeping them in an enslaved state is not the healthiest thing for them. They get old and they die.

Logistically, were you actually prepared to travel as much as you do in order to find those chimps?

We knew that the law is slow and it would be a long [process]. We didn’t think it would be the three or four years it took. In documentaries, the rule of thumb is that if it takes you longer than a year to make a film, you’re probably not going to get its costs back, so you’re taking on a heavy piece of business and you have to be prepared to hang on. You don’t want to quit once you’ve got it going. And the story is still going on as far as Steve’s concerned. They’re initiating two new cases and we could’ve kept the film going, but we didn’t because it had an ending which you could see — an ending isn’t always what happens, it’s what people watching the film perceive as covering the arch that the story always suspends.

I’m likely wrong about this, but was this actually the first time you had to shoot in a courtroom?

No, but it’s hard. Usually, you get very limited access. Chris really went to the judges, and the first two, there was a little problem because [the courts] generally don’t do sound, they just do a picture and then they talk over it. It’s for a TV station, and somebody then tells you what’s happening. To be able to hear what the judges are saying and get good sound is hard unless you can plug into a system that works, and most of these systems didn’t work very well so we had to put wireless mics on. It was complicated to do, but when you’re doing a film like this, that’s part of it. On an earlier film we did many years ago, we had a person come in and do animation, like the old newsreels. But in this case, we got into those courtrooms and people welcomed us in because they understood that it was an important case and that the public was interested. That was interesting, because that alone told us that we weren’t on a blind date here.

That’s because we have this small, portable camera. You could put it on your shoulder or hold it under your arm. It’s small enough so that you can follow somebody or get a close-up of their face, which is really important. If you set up a tripod and a camera with a long lens, it’s hard to get a good close-up of people. There’s too much magnification required, but we learned this when we did “Monterey [Pop],” which was the first time that we really used these portable cameras. Before that, I had one that I used, but I did it all by myself. With “Monterey,” I could give these cameras out to people that worked with me — they weren’t even cameramen really, but they could then go do what they wanted to do with it — and I didn’t even know what they’d done until I’d seen the film made. It was like turning a lot of people loose whom you trusted to do good things with it.

With digital, has it been an interesting transition to know what you’ve shot immediately?

I’m not sure it helps, but maybe. It helps some people. I don’t try to edit [a film] together until you’ve gone pretty far, but we had to do it a little bit here because we needed to decide how close we were to getting to an ending. We did tend to put it on the editing bay and take a look at some of it, but [usually] we don’t try to edit it until it’s pretty much shot because you don’t want to think that final thought until you’ve had it, otherwise you start making too many different films.

What’s it been like traveling with “Unlocking the Cage”?

We’ve showed it in different places and it’s interesting because it’s a universal reaction. In Europe, they’re as interested in our relationship with animals as people are here, which is unusual because I think 20 years ago that wouldn’t have been the case. I think it’s because of the change in our perception of animals. We’re going to stop eating them soon just because it’s too expensive to raise animals for food. We’ll start eating imitation meat and everybody will get used to it, and it won’t affect much at all. It’ll just be the way life is. Our relationship with animals will change – all animals, maybe even bugs and ants. They all communicate, and we may not be able to understand what they’re saying, but all life, even microbes, probably have ways of communicating that we have no idea about, but we’re going to start learning [from] them because in the troubled planet that I see coming up we’re going to need to know a lot of things that we don’t know now about survival. And survival is what communication is about.

The thing that’s intriguing, and why it’s grown to be such a worldwide phenomenon, is everybody loves to create something and the thing you create most is conversation. To make a film before the 1960s, nobody ever thought to make a film on themselves because you’d need a studio, you’d need people. Suddenly, we modified the camera so it was portable and synchronous so that you could film anywhere with somebody. Suddenly, a person could make a film all by themselves. It was like novel writing — that moment when people discovered that they could write a novel by themselves. They didn’t need anything else to do it. That aspect of it fulfills the part of us that’s creative. You don’t need a company to finance you necessarily, you can just do it. If you want to distribute the film, then you need to get money and it’s not easy to do, but people still want to [make films] just because it’s an adventure to try to make something as complicated as a film.

I hope you have a few more adventures ahead of you.

I don’t know. You can’t count on them, but they come to you because people see what you do and think “this will be interesting for this person to make a film.” A number of people now make these kinds of films and know how to do it. We employed a lot of them, and they’re now working independently. Two of my kids do it, and they’re quite good at it. There’s a lot of competition, but there’ll at least be somebody that’s decided that they want to have you do this film and they’ll come to you. We’re easy to approach. We’re not a big studio. They could come and say, “here’s a person who’s doing such and such, this is an interesting story” and you think about it. You don’t need to write it up or investigate it — you just start to do it. You use the camera like a flashlight to find out what’s behind the corners. It’s like a searching device. You don’t know what you want to do. You’re not directing anybody to do what you want them to do, you’re watching what somebody else does in order to learn something that you don’t know. The main drive is being curious.

“Unlocking the Cage” is now playing in Los Angeles at the Monica Film Center and in Brookline, Massachusetts at the Coolidge Corner Theater. A full list of theaters and dates is here.