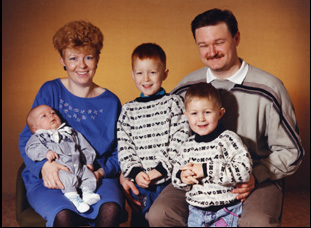

Like any child, the more his parents concealed something from Christian Einshøj, the more he was bound to become fascinated with it, which became a particularly delicate situation when his baby brother Kristoffer contracted a rare disease known as Histiocytose and it was rarely spoken of after the family moved from Denmark to Norway for treatment. His father Søren had purchased a video camera to preserve what time Kristoffer had left on this earth, a cold comfort that his life extended a year past the one year he was expected to make it, but put it down shortly after and at least to Christian’s eyes, never picked it up again. For his eighth birthday, Christian was gifted a camera after desperately wanting one, but as interested as he was in collecting his own images, he was equally intrigued by the ones that his father had created, sneaking into his room while he was away on a business trip to find a cache of recordings that he made after Kristoffer’s passing. Perhaps insignificant snippets to most, the scenes of nature were revealing to Christian, who may not have wanted to get in trouble at the time for snooping through things at the time, but included the scenes in his debut feature “The Mountains,” leading one to wonder whether his father was even aware he knew of the footage before sitting down to watch the film himself.

“I think he might’ve had a hunch, let’s put it that way,” Einshøj said recently. “But yeah, it’s not really anything we talked much about.”

If it weren’t for what the family didn’t discuss, Einshøj might never have felt compelled to make “The Mountains,” which sees the filmmaker utilizing the language of cinema to contend with grief when words fail, finding a door open when one seems to close on Søren after he’s laid off after decades as a company man and considers a move back to Denmark with his wife Eva. Though neither Christian or his remaining brothers Frederik or Alex, who was born after Kristoffer’s death, have stayed close to home, the prospect of selling the house they all grew up in is bound to cut off any remaining ties they have to Kristoffer and as Christian fears, to one another when although they never speak about the three-year-old’s death, losing him has given shape to their lives ever since. Refusing to let that happen, the filmmaker connects the myriad footage and photographs that his parents gathered over the years to his own chronicle of the family once he became the only one to want to document it, taking the additional step of traveling across Norway and beyond to talk to his brothers who each have a different perspective on what Kristoffer’s death meant for the family and the silence that followed.

Envisioning tragedy as an event that can easily lead to places as strange and absurd as it can to black holes of despair, Einshøj leavens “The Mountains” with a curiosity about grief, contending with how it can strike at unexpected times in unanticipated ways with equally atypical ideas such as a wry voiceover that reflects the filmmaker’s own soul-searching through contradictory emotions and an attempt to scale a summit with his brothers in superhero outfits that they wore in their youth, moving on from a point in their lives when time stood still. After the film recently premiered locally at CPH:DOX in Copenhagen and made its international premiere at Visions du Reel in France, it is now making its way across the Atlantic to Hot Docs in Toronto and amidst his travels, Einshøj kindly reflected on putting such an intimate family portrait together, how working through the story for an audience helped him understand it for himself and what it was like to show them for the first time.

Yes, it was the selling of the house that set off me going up there and starting to shoot everything and coincidentally, both of my brothers were also going through these crises. But this idea of making a film about my family has been going on for a long while —15 years or so, sorting through these old tapes and photographs and trying to find my way through them to assemble them into a story.

Originally, I thought it was supposed to be a film just from the old home video material — that would be 100 percent of the footage in the film, but I never had a very carved out plan, even when I go to film my father moving out of the house. He’s just been fired and going through this crisis, but I felt “Okay, now something very important is happening in the family and I should just start shooting now.” That’s what I did for two years. And in the end, [after filming] for two years, I sat down to try to find out what this is all about because I couldn’t know until I sat down and tried to assemble it.

It was actually incredible to me that you edited this yourself – when you were so close to the story, was it difficult to have perspective on it or did that make things easier?

Yeah, it was difficult and a big problem. I wouldn’t recommend it anyone. After you’ve gone through the film a couple of times, you just lose the oversight over it, so it took a long while. I spent three years editing, but also just writing the narration was a very slow process. In general, what this exercise of telling this story about my own family is enhance my sense of empathy. [The act of storytelling] forces you into trying to understand every character you’re working with, which is something maybe I’m not very good at doing in my just day-to-day life, so it forced me to have empathy for my parents and my brother. whereas before, there might be more petty feelings or minor annoyances that takes up more space [in my mind].

It was a great experience. It’s a brilliant Danish composer Toke Brorson Odin, whom I’ve also worked with on my previous film and we spent three months in his apartment with his keyboard and synth setup and just freestyled our way into the sound of the film, so it was very enjoyable and I’m very happy with it.

I gather that your family may already be quite comfortable with you holding a camera all the time, but was it something that opened up conversations that you might not have had if you weren’t making a film?

For sure — certainly the stuff I’m doing with my brothers and [seeing] them open up about their problems. I don’t think that would have happened if the camera weren’t present, and I wouldn’t have been able to ask the same questions. Weirdly, they also might not have felt comfortable sharing it without the camera being there, so it helped [having] this external reason for going into these [informal] therapy-like sessions. It made it easier for both of us.

Yeah, it already premiered in Copenhagen, so they all went to the premiere, but they also saw it before anyone else and that was pretty intense. My parents [knew what had happened], but also they didn’t know any of the stuff that my brothers were talking about [regarding] suicide and my youngest brother’s weird situation with his placement in the family coming after my brother’s death. So for them, this was sort of shocking, and obviously [they’re just] learning this for the first time. But I talked to my brothers beforehand [about] how they want to handle it, and they wanted me to show my parents the film, so I would sit by myself with them and that would be be their way of telling this stuff.

What’s it been like for you to get this out into the world after being so close to it for so long?

It’s really fantastic now, just being finished and it being over, so I don’t have to sit and deal with this every day, trying to figure it out. People are very happy with it, so I’m happy.

“The Mountains” will screen at Hot Docs on April 27th at the TIFF Bell Lightbox at 6 pm and April 30th at noon at Scotiabank Theatre 5. It will also be available to stream across Canada from May 5th through 9th.