When “Wild Wild Country” premiered at the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year, Chapman and Maclain Way were ever so slightly concerned about whether anyone would show up. Despite charming audiences four years earlier with “The Battered Bastards of Baseball,” gleefully recalling the 1970s heyday of the independent minor league club Portland Mavericks run by their uncle Bing Russell, their follow-up was a six-part miniseries nearly 400 minutes in length, a long time to ask anyone to sit in one place, let alone festivalgoers eager to pack as much into their Park City experience as possible. It also wasn’t the first time that they had their doubts about recounting one of the craziest stories they’d ever heard – of how the town of Antelope, Oregon (population: 115) had been invaded by the Rajneesh movement, led by an Indian guru named Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, to set up a commune where they could be free to create their own laws.

“When we were making this, we were always asking ourselves, are people going to be confused by hearing both sides? Or are they going to feel entertained by it? And we just kept doubling down on this feels good to us as filmmakers,” said Maclain Way, shortly after filling up the Egyptian Theater.

Added his brother Chapman, “Watching all six episodes, you really create a bond with the people that stayed around that long to watch it and really build that camaraderie that you’ve really gone through something unique and special.”

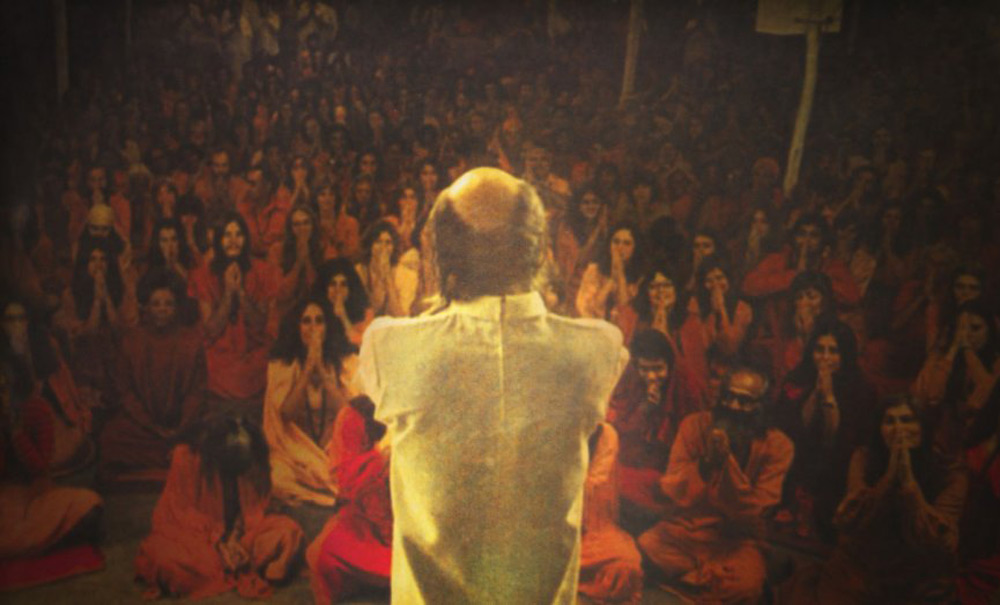

In fact, the challenge with “Wild Wild Country” isn’t sticking around for its duration, but trying to tear yourself away. Tracking down nearly all the living key players in places as remote as Maisprach, Switzerland and Perth, Australia, the Ways recount what went down in Wasco County as vividly as it remains in the memory of those who lived through it, where uzis were stockpiled and mass poisoning plots involving strains of salmonella were hatched. Of course, there’s incredible irony in how such ugliness is born out of a religion that strives for utopia, preaching a philosophy called dynamic meditation that combines the tenets of Buddhism with psychotherapy. After wearing out his welcome in India where his growing influence was seen as a threat, Bhagwan set his secretary Ma Anand Sheela to find a new home, ultimately locating 63,000 acres in the Pacific Northwest that could house 10,000 disciples. Yet in the quiet community populated largely by retirees who enjoyed their status off the map, the new age emigres searching for spirituality and big believers in free love were most unwelcome guests.

A battle of epic proportions ensues in “Wild Wild Country,” but in bringing together all involved in the conflict in Antelope as it was transformed into a new town known as Rajneeshpuram, the miniseries transcends the sensational intrigue of the feud with all its big personalities, none more so than the fierce and determined Sheela, to become engrossing in a multitude of other ways. Observing how the Rajneeshees work inside the laws set forth by the U.S. Constitution to essentially live outside of them in establishing their own city, “Wild Wild Country” burrows deeply into social and cultural attitudes behind the two sides standing their ground, delving into issues of religious freedom, property rights, immigration and the devious political machinations deployed on both ends to exert their will. Although the conflict captured the public’s imagination once before as the Rajneeshees and state officials in Oregon once made the media their battleground, “Wild Wild Country” is liable to make it so again and as the miniseries arrives on Netflix in its entirety, the Ways spoke about getting their arms around such a sprawling story, the interview tactics they used to get the most out of their subjects and the modern-day parallels they grew conscious of as they were making the film.

Chapman Way: It started about four years ago during [“Battered Bastards of Baseball”]. We worked with this really great film archive, the Oregon Historical Society, and one of their archivists told us that he had over 300 hours of never-before-seen footage on what he described as basically the craziest story that ever happened in the state of Oregon. He started telling us a story of mass poisonings, cults and assassination and murder attempts, so our ears definitely perked up. We started transferring 300 hours and the footage that we got back was absolutely mesmerizing and strange and beautiful, so we knew that we had something special on our hands and dug in.

Did you know from the start it would be a miniseries as opposed to a traditional feature?

Chapman Way: Just [with] the amount of archive footage, we realized that the magnitude of the story was just so huge because it starts in the ‘70s when this Indian guru Bhagwan Rajneesh built this huge massive following of Western followers and then they moved to America in 1981 to build this $150 million utopian city. Then [they] stayed in Oregon for five years, so the scope of the story took place over many decades and there were just so many big story beats that we really felt from the beginning, [with] all of that amazing archive footage, would be best told on this bigger canvas, [which] really gave us the opportunity to show two really deeply different views of how this story unfolded. You get to hear the perspective of the local Oregonians, and you also get to spend time inside the commune with the followers and that bigger canvas really allows the audience to become fully immersed in both sides of the story.

Was the Rajneeshee footage part of the archive or did you have to go somewhere else to find that?

Chapman Way: The archive footage [came from] lots of different sources and shot by many different people. The majority of our footage came from the local news affiliates, who were given free access to do these news stories on the ranch. They had decided back in 1985 to preserve these U-matic tapes they had filmed on and not re-record over them for their local nightly newscasts, so they were donated to the Oregon Historical Society. We also have some homemade Super 8 footage that was shot by some of the Sannyasins on the ranch. There are also some local camera guys that shot their own footage and the organization itself made their own kind of propaganda pieces that they filmed, so it really was an array of sources.

Chapman Way: Yeah, as soon as we got the archive footage back, Sheela jumped off the screen as this really fascinating, complex, strong character. We were immediately drawn to her and knew that she could be our lens for our story. We were able to track her down in Switzerland where she now runs a retirement home and I think she realized from the moment we talked to her [that] we weren’t there necessarily to judge her for her actions or the attempted crimes she was accused of. I think she felt like she had never really gotten the chance to explain her version of events from beginning to end, so as documentary filmmakers, she was an incredible subject.

She was very open and actually really brave. A lot of our other interviewees wanted our questions beforehand to prepare and she was the only one who said, “Don’t send me any questions. If you fly out to Switzerland, I’ll sit down in that chair and I’ll interview with you guys.” We spent five days interviewing her in Switzerland, so we ended up with over 20 hours of interview footage with her and she’s just an incredible character.

I loved how you shoot the interviews in this film, where the environments tell so much about the subjects. How much of that is negotiated with the person sitting in front of the camera?

Chapman Way: Our DP Adam Stone, who’s well-known for shooting all of Jeff Nichols’ films, has got an incredible eye and is really great at these artful compositions, and we talked very early on about not framing for the character – like shoulders up, [with] a couple inches of headroom – but to really frame for the space [they inhabited]. We really felt the spaces for these interviews tell you a lot about the characters and give you little insights into who they are, so we really framed for the room and then find interesting places to place the interview subject in that room, but that was really a discussion between the directors and the DP as to how to bring a sense of space and tone and environment to the series.

Chapman Way: Absolutely. The first people we got to know were a lot of these Sannyasins and these Rajneeshees and ex-Rajneeshees. It was very interesting once we started talking to them [because] we saw how these were highly successful, intelligent people who really got burned out on life and joined this spiritual movement, but when they would talk about the other side, they talked about the Antelopeans or Oregonians as these really one-dimensional, backwoods bigots who didn’t understand what they were doing. Then once we got to spend time with some of the Oregonians, we saw some of those concerns were justified, but they had multiple dimensions to them as characters and human beings as well. And then they would also talk about the Rajneeshees as these one-dimensional, evil people who took over their town. So there definitely was a little bit of whiplash to realize even 35 years later how much these two groups really despise each other and haven’t really found any resolution to this experience.

Something else that seems key is how limited a range of subjects you have to keep this so focused – perhaps it’s culled down from the amount of interviews you did, but how did you decide who to talk to?

Chapman Way: Yeah, Mac and I talk about that a lot as directors. One of our pet peeves are some of these documentaries that have so many talking heads, you never quite know what the purpose of each character is for in the story, so we really try to limit the amount of talking heads we have in our series for a narrative purpose or to explain something very specific. By doing that, you really get to spend a lot of time with these characters and it builds a sense of intimacy between the audience and the subjects.

Maclain Way: Yeah, and in a longform [series], what’s interesting is that at the beginning, it’s definitely two-sided. You’re getting Antelope’s perception of the events that happened and then you’re getting the Rajneeshee’s perception, but as you start to work your way through the series, especially in episode four, five and six, you start to see our main characters [in] the Rajneeshees – Sheela, Jane, Niren – start to have a real difference of opinion amongst themselves on what started happening, which I think is a little bit hard to do in a feature, but when you’ve limited the amount of talking heads, that becomes entertaining in and of itself, seeing people who used to be on the same team really start to talk to the audience with very different perceptions of what happened.

Chapman Way: Brocker is one of our best kept secrets. He’s an insanely talented composer and just incredible with these orchestral arrangements. At the end of episode one, Sheela calls this story of Rajneeshpuram an opera, so we took the creative liberty to run with that and create this really big operatic score. We wanted each character to [have a specific] score, so if you’re hearing from the perspective of Oregonians and Antelopeans, that’s going to be a whole different orchestral arrangement than when you’re hearing from the Rajneeshees or when you’re hearing from state officials, which is a little bit more of an electronic, gloom and doom sound. So we didn’t have one overarching score that we peppered in throughout. We had these really different thematic arrangements for whoever was telling the story at that point.

We love working with Brocker and he an I do music ourselves – we’ve released an album together – so we talked very early on in the process about what we wanted to do musically and he’s able to write and compose while we’re editing, which is really unique. Most documentaries wrap their edit and then the composer has four to six weeks to score the whole thing, but he was right there the whole time with us, writing and composing as we move through it.

Maclain Way: Yeah, we track all our instruments and record it and the [music is] this side production that’s running alongside the film production and that goes back to “The Battered Bastards of Baseball” [which] Brocker also scored. I think there’s something that’s really special when you have this big, thumping orchestral movement that plays over archive footage because the orchestral sound is so clean and new and it feels very pure, but the archive footage is so very beat up. It has a ton of artifacts in it and [the collision of the music and the image] lends itself to creating little moments of magic in documentary filmmaking.

If you were making this over the past four years with the likes of Cliven Bundy in the news and the way the country seems to have dispersed into these cultural silos that are separate from one another, as exemplified by the recent Presidential election, does it influence the way you tell this story?

Chapman Way: It’s really interesting because we actually did all of our interviews before the whole Trump presidency and we had already started cutting it, so it didn’t really factor in at all into our series. But it still is amazing how relevant all of these issues are today of religious fanaticism, of the other moving into new communities and how they’re treated, the separation of church and state and the establishment clause and how that makes it really fun to watch and dissect 35 years later.

I also think what makes the story fun is that it’s hard to interpret the story through today’s political lens because the politics of the story have been inverted in a really interesting way where you have a Christian conservative group in Oregon trying to limit the scope of what this religious movement can do and limiting freedom of religion, which you wouldn’t expect Christians to be doing. And then you have this spiritual hippie commune who takes up the Second Amendment and arms themselves to protect themselves and gets involved in politics. So in a way, audiences can’t just apply this black and white, left/right filter to the story. You really have to dive in on a personal level and figure out for yourself exactly how you feel about each of these episodes.

Chapman Way: In today’s political realm, I think this story does show what happens when two sides completely refuse to come together or understand or communicate with each other at all. Both of these groups just got more and more ingrained in their own belief systems and more and more militant [until it] ended up just becoming this huge clusterfuck, so it’s a really interesting exploration of what happens when two sides completely refuse to see each other’s perspective at all.

“Wild Wild Country” is now streaming on Netflix.

Comments 1