“If you want to pass the story on, you’re going to have to write it,” Tommye Myrick said towards the end of the evening celebrating “Cane River” at the Academy of Motion Pictures and Sciences’ Mary Pickford Cinema this past Friday. “There’s a place for our stories, but we’re going to have to write them.”

Myrick has done just this over the years, serving as the artistic director of the Voices in the Dark Repertory Theatre Company in New Orleans, but she was describing the considerable risk taken by Horace Jenkins in 1982 when he embarked on making “Cane River,” an all-too-rare slice of African-American life that has taken a more remarkable journey to the big screen than most. Finding financing, eventually through a family of morticians in Louisiana, where the film is set, proved to be only half the battle for Jenkins, who sadly passed shortly after making the film at just 42 years old, leaving no one else capable of pushing it uphill to get the wide distribution it deserved and after becoming a sensation at select screenings at Ebertfest, the Walker Art Center and MoMA’s “To Save and Project” series, the film will finally have a proper release nationally through Oscilloscope in February 2020.

As remarkable a story as there is behind the resurrection of “Cane River,” it may pale in comparison to Jenkins’ own history, which suggests that he could’ve made his mark in films as much as he did in television if he only had the time. Educated at the Sorbonne Film Institute, he returned to America to become an innovator on public television, serving as an originating director of “Sesame Street” and developing the news magazine format that became popular across the spectrum. At the Academy event, his daughter Dominique Jenkins, described “Cane River” as the perfect distillation of who her father was as a person – “someone who could be funny and serious at the same time” with a deep passion for education, which manifests itself in a variety of ways in the story of star-crossed lovers Maria (Myrick) and Peter (Richard Romain).

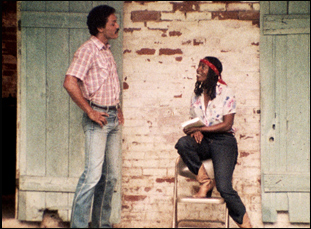

From the way “Cane River” eases one in, settling in the dandelion fields where Peter can pursue his interest in poetry, it wouldn’t seem like there would be much conflict alongside the bayou, but the tensions that have run deep throughout the community for centuries gradually reveal themselves after the couple first meet. While Maria is a Baptist from Nachtitoches, Peter is Catholic and creole by blood, with roots that trace back to Marie Thérèse (CoinCoin Metoyer), a former slave who eventually inherited some of the land owned by her former owners and was suspected by some to keep slaves of her own at the Metoyer plantation, and although Jenkins makes plain the ways in which the theft of land from the African-American community is central to the issue of racial inequality once Peter starts consulting with lawyers, the issue can be seen more subtly in how it shapes the perspectives of its central characters, with Peter eagerly returning to a less complicated life on his family’s farm after having the luxury of turning down a career in pro football to follow his passion for writing while Maria can’t wait to leave for Xavier University, which comes at considerable expense to her family but feels as if its her only opportunity to do something with her life.

Still, a whirlwind romance commences between the pair and complicates things, particularly when Maria’s mother (Carol Sutton) can’t believe her daughter is dating a Metoyer, and Jenkins is able to craft both a charming romance and an important history lesson that never feels like one, reaching both the past where “Cane River” grapples with colorism at a time when it was rarely considered by showing the rift between the creole community and their neighbors, and presenting a reflection of the times during the 1980s in a vibrant area that hardly ever attracted the attention of cameras, creating a record that wouldn’t exist otherwise. Even though neither of its leads were professional actors at the time, Jenkins positions them well to look the part as the whole film resembles Hollywood romances, complete with power ballads and swoony falling-in-love montages, to rightfully place it in the same context while refreshingly portraying an experience that has eluded mainstream cinema in the years before and since.

Still, a whirlwind romance commences between the pair and complicates things, particularly when Maria’s mother (Carol Sutton) can’t believe her daughter is dating a Metoyer, and Jenkins is able to craft both a charming romance and an important history lesson that never feels like one, reaching both the past where “Cane River” grapples with colorism at a time when it was rarely considered by showing the rift between the creole community and their neighbors, and presenting a reflection of the times during the 1980s in a vibrant area that hardly ever attracted the attention of cameras, creating a record that wouldn’t exist otherwise. Even though neither of its leads were professional actors at the time, Jenkins positions them well to look the part as the whole film resembles Hollywood romances, complete with power ballads and swoony falling-in-love montages, to rightfully place it in the same context while refreshingly portraying an experience that has eluded mainstream cinema in the years before and since.

That potential is what likely made Richard Pryor interested in finding a way to distribute the film through Indigo Productions, a company he set up at Columbia Pictures where he was one of the top stars. After sneaking into “Cane River”’s premiere in New Orleans in disguise, Pryor set up a meeting with Jenkins shortly after, but a deal couldn’t be reached and once the writer/director suffered a fatal heart attack, the film went into storage at DuArt Film and Video in New York with few other remnants of its existence in the outside world. The closure of DuArt’s photochemical labs in 2010 prompted the Academy to take a number of films, mostly of unknown origin and set to be destroyed otherwise, into its own preservation facilities and Ed Carter, the Academy Film Archive Documentary Curator, curious about the canister simply labeled “Cane River,” began the detective work of learning more about it when having only a negative on hand, it couldn’t even be properly screened.

On Friday night, the Academy’s Managing Director of Preservation and Foundation Programs Randy Haberkamp was still asking anyone in the audience who participated in the production of “Cane River” to come forward and share their stories since so much remains shrouded in mystery. But Carter had connected the dots enough after tracking down the film’s editor Debra Moore, who tragically passed away just a week ago, to begin marshaling the resources needed to pave the way towards a restoration, engaging the team at the preservation organization IndieCollect, led by Sandra Schulberg, to locate funding through the Roger and Chaz Ebert Foundation, Just Films/Ford Foundation and the Amistad Research Center of Tulane University. The western wear that adorn Maria and Peter and earnest love songs may give the film’s place in time away, but from the pristine new 35mm print “Cane River” looks as if it were made yesterday, honoring the fact that it’s insights remain fresh as ever.

Myrick, Romain and Dominique Jenkins joined Carter and moderator Brickson Diamond on stage to talk about the making of “Cane River,” which like its road to release, required a few lucky breaks. While Romain could relate to the character of Peter, having once attended LSU on football scholarship, he wasn’t looking to be an actor when Jenkins offered him the part, ultimately deciding that taking the role would be preferable to relocating to Birmingham for his work with AT&T. Myrick also wasn’t particularly keen on acting, concentrating on a career in directing when a friend had told her that Jenkins needed a new leading lady after the first actress to play Maria left the production a short time into filming. Asked just two questions by Jenkins, “Can you swim? and “Can you ride horses?” Myrick answered in the affirmative, though she couldn’t and quietly snuck in swimming lessons from Romain over the course of shooting with Jenkins being none the wiser.

What the two may have lacked in professional polish, they make up for in chemistry and by the end of filming, Myrick and Romain were seasoned pros, to the extent that when Jenkins realized the film was missing a scene where Maria could be directly confronted by her mother and the film’s cinematographer left for the night, Jenkins set up a camera on a tripod and Myrick and Carol Sutton, who played Maria’s mother, improvised an entire scene that became one of the film’s most memorable moments, unfolding all in one unbroken take. The two recalled a joyous set and Jenkins reminded that her father enlisted the film’s composer Roy Glover early enough in the process so that his music was actually played on set during the scenes it plays in the film to set the mood.

Unfortunately, for many involved on “Cane River,” their first film would also be their last with no one able to appreciate their work when the finished film was sitting on a shelf for the past three decades, and Dominique Jenkins was adamant in her belief that a release in 1982 would’ve “changed filmmaking for black people,” providing a “playful and light” counterpoint to the highly sexualized and aggressive depiction of African-Americans on screen of the exploitation era that “Cane River” could be seen as a response to and hasn’t entirely gone away in the years since. But as Myrick said, “a delay is not a denial,” and the unique path “Cane River” took to the screen is proof that some stories simply can’t be denied.