The sea is speaking out to Zinwe (Uzoamaka Aniunoh) when “Mami Wata” begins, but though she walks towards the water, she is reluctant to heed the call. It isn’t the supernatural element she can’t fathom when her mother has been long believed to be an intermediary between the spirit and human worlds connected by the ocean, but like any rebellious daughter, she is suspicious of the motivation behind it. Plenty of questions are raised in the community when Mama Efe (Rita Edochie) is no longer seen as the deity she once was, with rumors swirling that her once unquestioned powers have diminished as fewer people are coming to her ceremonies and those who attend are receiving unsatisfactory answers, such as a grieving mother who lost her own child who is told her “child isn’t dead, she just went back to where she came from.” Zinwe is among those increasingly fed up with her mother’s smugness in her old age, expecting deference in all matters that she’s issued a verdict on even when it’s sensitive to the people who come to her with their concerns, and while the bloodline of succession suggests Zinwe is the next to take over, she isn’t so sure.

Mama Efe may be losing her mystique amongst her parishioners, but the film in which she is central is spellbinding, with the ever-present sound of rolling tides in the background washing over you. But beyond the immersion into the environment, you can easily get lost in C.J. “Fiery” Obasi’s fierce drama where Zinwe’s own doubts about taking over for her mother upon her eventual death are only one reason for concern in the coastal community when a stranger named Jasper (Emeka Amakeze) shows up to town, rescued from drowning by Zinwe’s sister Prisca (Evelyne Ily Juhen). Said to be a war deserter, uninterested in fighting for the national army or the rebels, he can easily become enamored of a place where there is a simpler way of life yet also dissatisfied to see that certain urban amenities such as schools or hospitals or police haven’t been established. The world the women in the village have built appears to be functioning just fine and when a power grab can be made with Zinwe’s ambivalence manifesting itself into an outright disappearance, Prisca is caught in the middle, having grown close to Jasper after helping to nurse him back to health and trying the best she can to do what’s in her family’s best interests, though she’s not deigned to assume Mama Efe’s position when she’s adopted, even if she’d be a stronger fit for it than her sister.

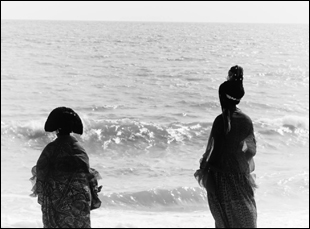

While the story is rooted in West African folklore, “Mami Wata” feels entirely in the present tense, if not the future, when its stark black-and-white imagery proves so refreshing to the eyes and tackles intersections of power occurring everywhere in the world in terms of gender dynamics and religious belief, caught in stasis over adhering to tradition versus adapting to a modern world. Sparks fly in these conflicts on their own, but Obasi shows muscular direction in handling the action once they stop being theoretical dilemmas and become issues of actual combat, delivering a satisfying thriller on every level and upon its premiere at the Sundance Film Festival, he spoke about how “Mami Wata” had to come from the heart to work as a compelling film and the near-decade he spent developing it after the story came to him in a vision.

I always try to give the real origin of it. Maybe [it was] somewhere in my subconscious, because let me not be too thick to say I never thought of making a Mami Wata movie because I’ve always been fascinated with the mythology and folklore surrounding Mami Wata. It’s always been a subject of mystery and even taboo due to Westernization and to religion — Christianity and Islam. Some of these cultural aspects of our society have become demonized, but I’ve always had a fascination for this. And the way to make the movie came to me literally as a vision and I entered a trance. I can count maybe three or four times in my entire life – the first time was as a kid, the second time was as a teenager and the third time was “Mami Wata.”

I found myself on the beach, and I look across the ocean and I see who I believe to be Mami Wata, coming from the description that we know of her, stories from our grandmother and so on. She’s standing on the beach — this beautiful, gorgeous goddess, dark skin, long locks covering her entire body, and glowing skin like bronze. But all of this is in black and white, so much so that her skin is shining black. The, the sky in the horizon is deeply dark, almost like a storm is brewing and her eyes are red — that’s the only color in this thing. She looks at me and right through me, so I turned and I see a young woman walking towards me and she walks right by towards the goddess, and I come to.

When I come to, I tell my wife, who’s my producer, [this is] the next movie I want to make. She goes, “Yes, let’s do it,” and this was January 2016. Then I started to work on the script and I wrote maybe eight or nine drafts between 2016 and 2018, but it was more in the vein of a genre revenge-type of film. Even though a lot of people read it at the time and they were like, “Man, this is amazing,” to me, it wasn’t good. It felt very generic and I knew that wasn’t the feeling I got from that [experience], so I was still trying to find that feeling. I started doing film labs in Africa — [one] in Burkina Faso, and we went to South Africa to do further development, then we went to Poland, to Norway, to Romania, different labs across the world for a period of two years, just working with some of the best story consultants and script doctors in Africa and Europe, until I went on my own personal journey to dig deeper into myself. Here we are, seven years later since inception at Sundance.

It was all worth it. The film manages to be very specific and universal at once in terms of all the intersections of the consideration of gender dynamics and spirituality versus secular religion. Was that all part of the initial vision or did that come in over the years of development?

When I was working on the script by myself, it was a very traditional genre piece, which maybe would’ve been a certain kind of success, but I wanted it to say something more because when the vision of the idea came to me, I wanted to tap into something. I wanted to tap into my love for cinema because even though it’s my third feature, it felt like my first to a large extent because I was going where I hadn’t gone before. But really what allowed me to find that were the very personal thoughts that maybe I was scared of finding in the first place, so you just try to figure it out by using genre to cover it up. As soon as I started digging into things like why I want to tell this story and why it means something to me, I realized that it was really rooted in my sisters. That’s really where I found the journey and path to creating Prisca and Zinwe, the two sisters who take us through the entire narrative.

How did you find these wonderful actresses to play them?

How did you find these wonderful actresses to play them?

Because we started casting in 2020, so it was still in lockdown and I wanted a cast that reflected the West African nature of the story. The alternative title is the “West African Folklore” because it’s a folklore that is rooted in all of West Africa, whether Anglophone or Francophone countries. It’s a unifying tale, as far as West Africa is concerned and I wanted to reflect that in the cast. We put out a casting call across West African countries to our various connections and we got almost 1000 submissions from Nigeria and other West African countries.

I had to watch every single one of those submissions and I’m watching all the submissions projected it on a 65-inch screen TV, and when I saw Evelyne Ily’s, I was watching with my producer and I told her, “Look, that’s Prisca.” And that was it. Even then, she didn’t even know how to speak English at the time, but she’s from the Ivory Coast, so she learned English just enough to deceive me just to get the part. [laughs] That interested me a little further [because] she really wanted the part and I told her, “As long as you’re willing to learn, I believe it,” because it’s a bit difficult learning English so that you can speak Pidgin, because the entire film is in Pidgin, but you have to learn English to speak Pidgin in a way, so she did two things to be able to deliver on the part, and I just thought that was phenomenal.

For Uzoamaka, who played Zinwe, she wasn’t the original person we had cast and I had written Zinwe with someone else in mind, another actress who I really admired. But by the time we got to 2020, I think she had become a different person — even physically she had grown so much, and I really wanted someone that would look like a younger sister to Prisca, and she got involved in a different project, so I had to cast someone else. And I was really impressed with Uzoamaka because she really came in at the tail-end and just throw herself into it. I was lucky in that sense.

Your cinematographer Lílis Soares is Brazilian – was that a consideration when maybe she’d bring a different eye to filming in this region?

Yes, I hoped she would bring a different eye. I had a very specific vision about what I wanted to do with the film. I’m a guy, making a female-centric film and I’d like to think that I’m very in touch with my feminine side because I was practically raised by my sisters who I dedicate the film to, and not just to them but to all the women who raised me — African women who I don’t see in cinema. That’s really what his entire film is — a homage to African women. But at the end of the day, I’m still a guy, so there are things that I see that might not really translate the way it ought to translate when you’re telling a female story.

I wanted a woman of color [for director of photographer], but I wanted a kickass woman of color DP, so I was lucky to find her. I was pitching the film in Norway, one of the million countries we pitched the film, and I met this Mexican-Brazilian producer who asked me if I had a DP attached to the project. I said, “Not yet, but I’m looking,” and she sent me a few names. They were all fantastic, but something about Lílis stood out in the way she captured her image, and something in her bio also caught my attention where she said she’s looking to innovate how Black bodies are captured, and I felt like that spoke directly to what I was trying to do with “Mami Wata.”

When I sent her an e-mail and told her what I was trying to do with “Mami Wata,” she said something that blew my mind. Immediately, she replies to me and says that she’s doing her Orisha initiation. If you know what Orisha is, it’s the Yoruba religion and within the Orisha, you have the deity or the spirit known as Yemaya who is a mermaid deity. She was literally doing her initiation to connect to her African roots when this e-mail from this guy making a film about the water goddess deity comes to her, so it felt very fortuitous and like destiny that we would work together.

Remarkable. And you’re able to get the sensations of this place so richly in sound as much was image.

Remarkable. And you’re able to get the sensations of this place so richly in sound as much was image.

We filmed in a place that is very connected to the mythology of Mami Wata, so literally you’re going to find people there who [have seen] Mami Wata. If you see me filming in a shrine, we’re in the real shrine or if we’re filming in a sacred forest, we’re in a real forest because we went there, we spoke to the elders and got permission [to film]. We really connected to the energy there and if you hear the beach, it’s not stock sound, it’s literally from the beach. We recorded sound from there and from the forest and from the community. Even with the interior locations, with Mama Efe and where she stays, we literally had to set up and build her location right in the heart of the community, so if you are hearing sound from outside, it’s sound from the village and the people around. I tried as much as possible to keep the authenticity. Then with a kick ass sound designer and sound editor, Samy Bardet and Julien [Tournecuillert], they did a fantastic job.

After seven years of working on this, what’s it like to have a finished film and start getting it out into the world?

It’s amazing. Sundance has been a dream of mine ever since I wanted to make movies. When I was working in ICT, I used to have night shifts and I would stream old videos of Sundance filmmakers arriving at Sundance and I would just go, “I want to be here.” That has always been my dream, so when we got the e-mail — and I think we were the first film accepted, that’s what they told me — the excitement of that and having to hold that in [for so many months] was so hard. It’s a lot of emotion, but I still can’t quite believe it. It’s a dream come true.

“Mami Wata” will screen at the Sundance Film Festival on January 25th at 12:25 pm at the Redstone Cinemas in Park City, January 26th at 2:25 pm at the Holiday Village Cinemas in Park City, and January 27th at 2:30 pm at the Egyptian Theatre in Park City. It will be available to watch online from January 24th through 29th.