At a certain point in “Time Bomb Y2K,” the wife of a doomsday prepper explains how she was skeptical of her husband’s claims that the world might come to an end at the turn of the 21st century, convinced from his work as a computer programmer that the transition from adding “20” to denotations of the new year to computer code was going to sufficiently scramble bank operations and potentially missile launch systems around the world that the couple needed to protect themselves by retreating to a desert hideaway. However, she wasn’t as ready as he was to pack it all in until “reading all these articles on the Internet and [eventually] in the mainstream and realized it was a problem,” archival footage that it’s easy to feel somewhat superior towards when one knows that the world safely made it into the year 2000 without incident but makes one uneasy with how Y2K would presage an era rife with conspiracy theories and manufactured panic.

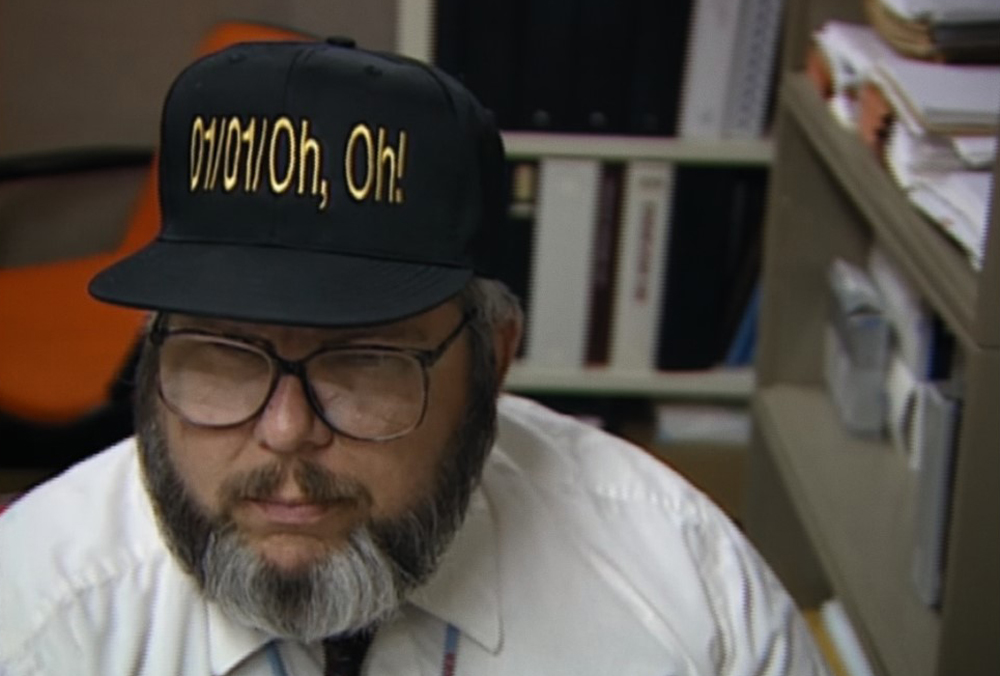

In fact, Y2K was not a hoax, as co-directors Marley McDonald and Brian Becker establish shortly after the enormously entertaining all-archival doc begins, with task forces set up around the world to correct code in anticipation of the new century, following the time and expense-saving measure of only using the final two digits of any given year with anything beyond the 1900s difficult to imagine when computers were first developed in the 1950s. However, that didn’t prevent those with genuine concerns – or far less admirable motivations – from sounding the alarm bell, most prominently a self-proclaimed “Y2K Paul Revere” named Peter de Jager, a former IBM employee who saw an episode of “Connections” in 1989 that detailed an entire city going dark with the flip of a switch and worried such a thing could happen with the entire world when it’s infrastructure moved so much online. Though his intentions appear pure at first, it doesn’t look like de Jager minds the attention of television appearances and by the time he reaches CNN “Crossfire” a few years into talking up the “Millennium Bug,” it’s noted that he’s selling merchandise on his Y2K website after wearing a doomsday tie on the show, setting up a revenue stream that plenty of others tapped into playing on people’s fears from gun dealers to major media outlets who led with news about the panic with nothing much to report on.

This level of attention may not have benefitted the public then, but it does, however, allow McDonald and Becker to cover a huge amount of ground now, charting a far more idealistic time for the Internet when then-President Clinton touted the ability for schools to have the same face-to-face video capabilities as the Pentagon as the likely precursor for more peaceful times and the way an influx of information that previously wasn’t as widely accessible could be used to support just about any idea out there amongst a certain subset of the population if not en masse. The naïveté is charming as “Talented Mr. Ripley”-era Matt Damon, Busta Rhymes and the Backstreet Boys opine about the potential disaster striking, but when trusted TV journalists such as Steve Kroft and Peter Jennings begin to legitimize fringe speculation by giving them air “Time Bomb Y2K” shows how the unknown is leveraged by bad actors looking to prey upon a larger and more susceptible audience than you’d expect. (And still, you don’t know now whether to envy or pity a woman known as “Farmer Jane,” who made the evening news herself for selling off all her assets upon de Jager’s advice and picked up self-sustaining agricultural skills that have probably served her well.) “Y2K” may not have been the end of the world, but McDonald and Becker brilliantly illustrate how fragile a society we have, less so for its technology than the public discourse.

“Time Bomb Y2K” will screen at True/False at the Picturehouse on March 4th at 10:30 pm and March 5th at 1 pm.