When Anca Damian had been working on her previous film “The Magic Mountain” when she came upon a stray dog with no owner in sight. She didn’t have time to care for a new pet in between traveling between from Afghanistan to France to Poland for work, but she was able to find a shelter that could place it with a family who could, ultimately turning into a series of homes for the dog that she’d keep tabs on over the course of a few weeks and while her initial interest was on the dog’s well-being, she became increasingly more fascinated by how the foster families seemed affected by their time with it.

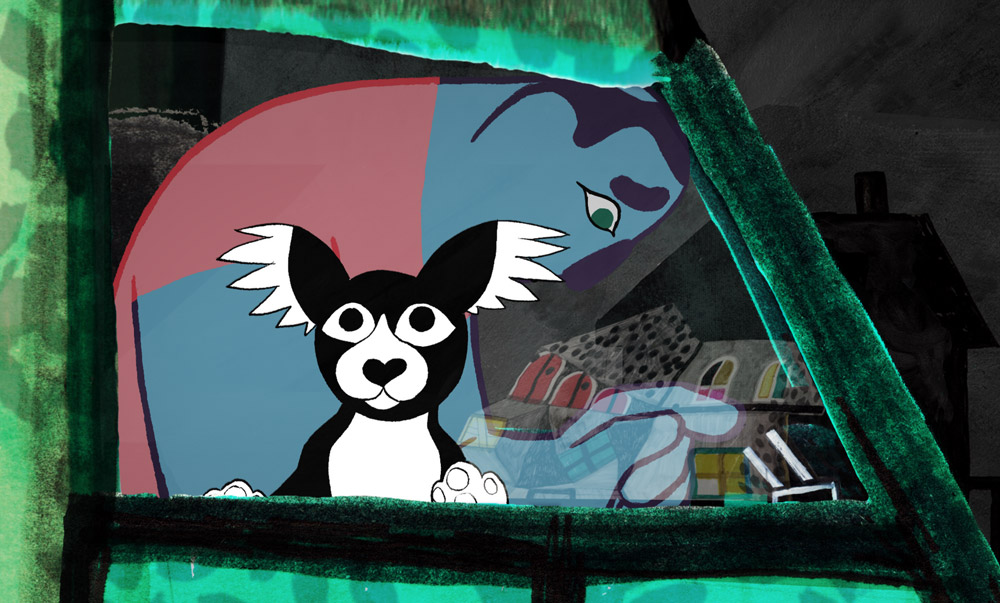

In the delightful “Marona’s Fantastic Tale,” which was inspired by Damian’s observations, people don’t just feel things but become the physical embodiment of their emotions when seen through the perspective of its titular canine whose life passes before her eyes, eternally in search of a home after being the runt of the litter amongst her own family. She finds her way into show business alongside Manole, an acrobat who exists in long flowing lines, and then at the beck and call of an engineer named Istvan, who is disinclined to socialize and resembles a statue with his broad features that Marona has to chip away at with her charm. She eventually finds it’s far less work to befriend an eight-year-old named Solange, with whom she seems to share a language, and while Marona is in continual peril when each situation isn’t ideal for one reason or another and taking on different names along the way, she brings out the best in whatever owner she has at the time, with Damian able to movingly capture the unseen influence a pet can have on its caretaker.

To show all the ways Marona’s impact takes shape, Damian blends a variety of animation styles and 2D and 3D characters to create a film of considerable depth both aesthetically and emotionally and “Marona’s Fantastic Tale” bursts with color even when it’s central character remains a humble black-and-white. Just as Marona sneaks her way into people’s hearts onscreen, the film that bears her name is liable to do the same after the film’s planned theatrical run following a celebrated festival tour last year was scrapped as a result of the coronavirus, instead being made available now through virtual cinemas. While Damian was in Los Angeles last fall for the Animation is Film Festival, she spoke about how the story literally found its way to her, finding the right format throughout to express the characters’ feelings and how she craves close collaboration to produce the most intimate results.

I was walking my [own] dog in the street in Romania and this dog was following me and I’m not Brigitte Bardot. [laughs] I’m not saving gutter dogs in Romania, but she had something special in empathy. She didn’t want food. She didn’t want anything. She just had this very delicate look, almost better than human in a way. [laughs] And I couldn’t let her go, so I tried to find a foster home for her for some time and then I noticed that the families that fostered her changed after her stay. I wanted to do a long feature animation about [something else] and I couldn’t get the rights and at the same time, this story became stronger. I felt we need this kind of movie for the family because so few things speak about empathy. How we relate, how we love in our life, how we interact and we care about each other is not at all a preoccupation of the society. It’s ignored.

It is funny because the movie I did two very seriously politically engaged animated documentaries, but even if they had humor, this film seems quite unexpected if you look at my previous work, but at the same time, it has quite a lot of things that are deeply rooted in me, [asking questions of] what is life and why we are born.

Did that help you figure out who you wanted this dog to meet along her journey?

The movie is organized in three chapters in a way that corresponds to childhood, teenage [years] and adulthood, so it reflects also three stages of our life. Everything is possible in our childhood, everything is marvelous, and [as] a teenager, you feel blocked, people get emotionally constrained, and in adulthood, they learn to love people as they are. I was doing a Q & A with children in France and they asked me how did you get this idea, and for the children I answered it in a different way, but I [said] “I received from a dog a package of love and she told me to do this movie for you,” and just like for children, I get something [ineffable] that touches me profoundly and gives me the energy to construct the vision of the whole movie. Of course every time the first drawings are not the whole movie and in the beginning, the vision is very high and then you fall again on the ground and start to take stairs to come there. [laughs] It’s just a process of [finding] the shape for this movie, and I believe if you see a frame, you should see this is from Marona. For me, it’s important to give each movie its language and also its visual identity.

One of my favorite things in the film is how you create distance spatially, but also in the idea that the dog can hear and the humans can’t. How did you want to show how the dog relates to the world around it?

Yeah, I didn’t have a dog until my son left a dog at home, and I have a quite crazy life [with] travel, so if someone is asking me what is your biggest problem in life, it’s how I handle having a dog. [laughs] At the same time, you learn from their point of view. You learn to live in the present. And perhaps if I didn’t own my dog, I would not be so attentive. I was joking with my artists, that when I’m very tired and want to wash my brain a little bit, I go on the site with lost dogs, and for me, there is a lot of purity in the interaction of a dog with a human. It allows you to see you how you truly are. It’s mirroring you in a way and there’s a lot of energy you can reflect in the dog.

At the same time, the dog gives you the simplest answer of what life is in a genuine way — the main issues of the life of how you look at each other and [how] all we have is the moment of here and now — [which is why it was important that] the only character that understands the dog for some time is Solange when she’s a child. She’s having a real dialogue with her, and children for me are born with a capacity that society destroys quickly [laughs] — a telepathic communication where you don’t need words because you understand things, an intuitive knowledge that we ignore a lot of times, so in a way this mirrors us because in fact, it is Marona’s story that helps us because she’s already in a way better than we are from the beginning.

How did the idea come about for the different styles of animation for humans?

I’m a visual artist, but I didn’t have any education in animation growing up [because] there’s no education for animation — last year is the first time that they made a section of animation [where I’m from], so while I use animation, I have the freedom to use the techniques without having this [idea], “This should be done like this.” The most diverse cinematographic language is animation, so I feel why should we cut our fingers and use just two instead of using [all of them] — recreating the space in the most effective way for each scene, you should use the means that you have because they are fabulous. So I make a concept every time I’m starting a movie, I’m making the concept on the space and how it should look and what is the perception of it and then I’m working with artists that bring their touch and we go even further than I imagined.

Each character is enhanced in the graphic design. [For instance, Istvan’s grandmother], the face is the map of her life in a way and the hair, so this kind of character design is very diverse in the movie. The grandfather [of Solange] is blocked, so if he’s blocked mentally, he’s a block as a character. If Marona can transform himself, [there are] the red lines are his energy, so they are shaping his body while moving — all these things were designed, and we describe the character and then we go further in graphical enhancement of their individuality.

For me, this diversity is unity, and this is something that it is rather unusual as a system of working [because] it is not industrial. I am more working on features with the freedom of shorts, with small teams and I’m in contact with each animator [every] morning and beginning of the afternoon. I’m traveling between all the small studios of five animators in three countries — in France, there were three studios, in Belgium, two, and one in Romania. I was keeping contact and they sent me the shorts to get feedback and discuss. It’s a process in which I’m connected all the time without an assistant, so it’s a very intense time and atypical because usually the director for a long feature animation, while the animatic is done, is delegating the assistant to do the follow and the assistant is even selecting the questions that get to him. For me, this system doesn’t work. There is an artistic flow energy that I’m warming it, I’m enhancing it, and I’m pushing people to go beyond their limits, so I need to organize [the production] like that. Of course, it is more exhausting because I’m working quick for animation. It’s one year of finance and one year of production. All together, it’s not more than three years from the idea to the finished product and I’m already on the next one.

I understand it was pretty special putting the music on this.

Animation brings all the arts together, so I always enhance the music and we discuss at length the animatic here and the character themes. While we recorded, it was in a studio in the Strasbourg region, so we couldn’t isolate the musicians [from the rest of the film team], so it was a very intimate way of [recording] because we weren’t isolated [from each other] in the mountains. Usually in a music studio, you are not in the same space with a musician. You are with the [backroom] guys and the musician is behind glass, but this time, we were together and we even communicated through the recording and it was a very special recording. Everything went in a very particular, artisanal way but very intense in emotion and very special in communication. We had the feeling that the holidays ended when the movie was over because it was an emotional way of being together.

Usually at the time of doing it, this energy of the movie is a hundred percent in you. Now I’m in my next project, which is completely different, but of course organically linked to [“Marona”] so releasing “Marona” is in a way is my child who is grown up, but is not anymore in my house. [laughs] It took its steps and of course, I think the most important thing is that the movie gets its audience. We’re doing it for for spreading ideas in the world. I believe that art should change the world — it should make people think differently, and usually, intellectual information stays shorter than an emotion, so this way of entering the heart through art is very important, and even if there are small changes in individuals, it is a start.

“Marona’s Fantastic Tale” is now playing in virtual cinemas, with proceeds split with you favorite arthouse cinema. A full list of theaters is here.