It isn’t every summer camp that has bunks named after the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda and slain Freedom Riders James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, but in part, that’s what led Amy Grappell to Camp Kinderland, a camp founded by Jewish activists in 1923 where all of the usual activities from hiking to putting on a play come with more than a dash of social conscientiousness. Grappell’s interest was piqued even more when she came to learn there were not just one, but two camps such as this in upstate New York when members of the Workmen’s Circle came to believe Kinderland was becoming too Communist-oriented in its early days and broke off to form their own Camp Kinder Ring across Sylvan Lake. Remarkably, both camps still exist to this day, as feisty as ever, though open to campers of every religion and race and “Kinderland,” which has been nearly a decade in the making, arrives when the lessons imparted to the young adults about caring for one’s fellow man and the impact their collective power can have are particularly resonant.

Grappell offers a visit to the camps in the present day where serious intellectual discussions about unionism are as common a pursuit as swimming, but remarkably, the director to trace what goes on there today to its origins as she’s able to interview a number of the original campers, now in their eighties and nineties, that illuminate the education they received there that they’ve been able to carry with them for the rest of their lives. If history doesn’t exactly repeat itself but it rhymes, “Kinderland” finds the poetry in it as the cultural divisions in America widen and remind of our most trying times in the past and campers can see a path towards a better future by reflecting on the past. With the film fresh off a local premiere at the Woodstock Film Festival, it’s heading to its big city debut at DOC NYC and Grappell kindly spoke about this eye-opening short that’s been long in the works, unearthing camp footage from the 1920s and the personal epiphanies that came from the process.

How did this come about?

I’m actually a third generation Jewish-American of Eastern European descent, and was raised largely by my grandparents and they were first-generation Russian immigrants and they spoke Yiddish, but they were really scared of identifying with their Jewish cultural history, so they wouldn’t really talk about where they came from. They just told me they were American when I asked and I was pretty confused, so when I learned about these summer camps, I had a special interest [because of] the Jewish cultural history and the humanist values they were teaching that were also secular – I’ve been secular from the beginning, and I really started to take pride in my own identity in a greater sense, so I think that really got me going. [laughs]

It was also really refreshing to learn there was a place where the mission is to teach kids to be better human beings so they can make the world a better place, and [when] I started doing a little research, I read an article about when [Camp Kinderland] started in the ‘20s and the one they started in upstate New York and [how] the socialist summer camp and the communist summer camp [Kinder Ring across the lake] were at war with each other. They would row their boats to the middle of the lake and call each other “dirty commies.” [laughs] So I thought, “Oh wow, this is really interesting” and just started feeling around, interviewing some of the people at the original camps in the ‘30s who were still around, and they blew me away. They had so much knowledge and experience that I thought could be so valuable to social activists of today. Many of them are in their nineties and I felt it was important to document them before they were no longer with us – a lot of them passed away over the period of making the project, so I’m really glad that I did that.

I noticed in the memorial at the end that one of the people you spoke to passed away in 2015, so have you been at this for some time?

I was, yeah. I learned about the story probably 10 years ago and whenever I was in New York, I would go and interview the elders I could find who would talk to me. I’d been collecting their interviews over a decade and then it wasn’t until 2019, I decided I really wanted to bring the movie into the present. Part of that had to do with Trump, but also [the camps’] whole deal of passing down these values to new generations. That’s at the core of the Jewish tradition L’dor V’dor, which means generation to generation and I [was] invited for about a week to go to camp.

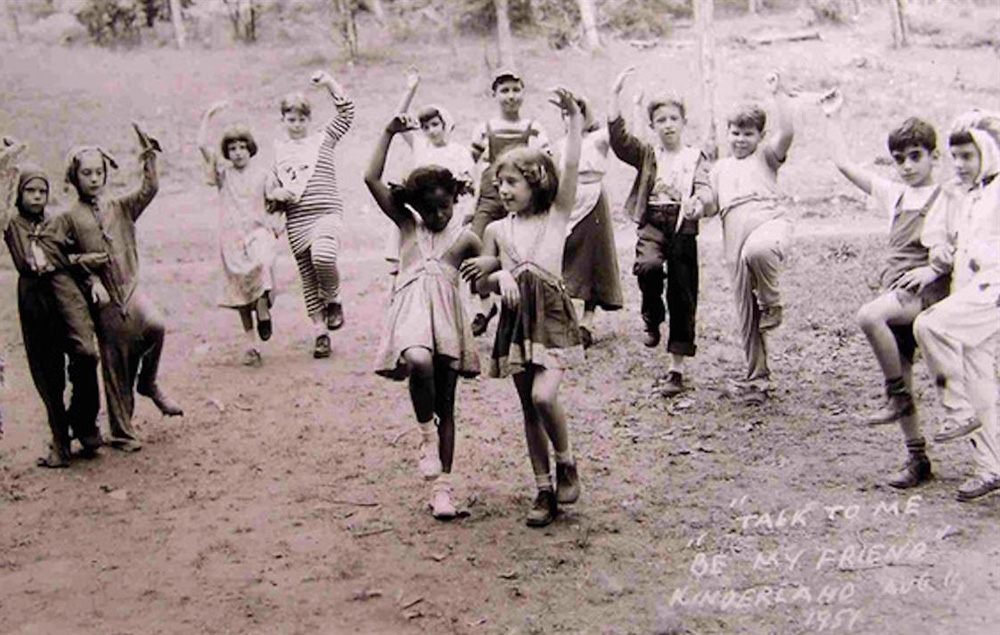

And I was surprised that they were doing a lot of the same stuff. They’re no longer across the same lake and there’s no longer that kind of active feud, but there is still a division between the two camps that they’re trying to mend and I kept seeing the past in the present and the present in the past. I started to visually see a circle of history, which I ultimately think is what comes through the movie. When I saw them doing “The Pajama Game,” I thought about all those photos of those performances, which were so dramatic in the ‘20s and ‘30s, things that now would not be PC. [Campers] dressed up as Ku Klux Klan members and they reenacted the Holocaust and the Spanish Civil War. They were radical, and I was hoping to see that – they don’t do it anymore. [laughs] But I was very impressed by how articulate the kids were and how much they had benefited from really knowing about their history and their cultural identity. They seem so acutely aware of how they can affect lasting change. They’re fluent in it and they’re very inspiring and very hopeful, and that’s a very refreshing thing these days.

When you mention the circle of history, it is quite striking at certain moments in the film how you break out into split-screen to express those parallels. What was that like to figure out?

It was very challenging, This one was heavy lifting. It really takes a lot to make something like the cyclical nature of history visually coherent in a way that’s experiential and as an artist, it was one of the more challenging films I’ve worked on in terms of how best to use montage to give people both the visual and aural representation of what they’re seeing and what it’s reflecting back on. I think film gives you that ability, which is what’s so incredible about it. You can really do anything. But I think that three editors in [would] all would agree, it was quite a challenge. [laughs]

You have some remarkable archival material from the camps during the 1920s and ‘30s. What was it like to find out there was such footage and photographs?

It took a lot of time and I was really lucky to find Ben Itzkowitz’s photography at the NYU Tamiment Library. The collection was donated by his family and that was a treasure trove that helped me significantly. I don’t think I would’ve been able to tell this story without it. I also spent quite some time at YIVO, the Yiddish Institute and Archive and finding the film stock was the hardest. There’s a wonderful archivist Huey Falk at Kinderland, [which in general] has also been super helpful. If there were no Huey, that would not exist and that really supports the story.

Was there anything that happened that changed your ideas of what this could be?

When I started out, I thought I was making a movie about what socialism was because what was so arresting talking to these people that it was really about humanism. It really wasn’t this scary, evil word that the right has bastardized so horribly and in a way, I felt I was somehow taking the darkness off the meaning of this word. Then it became apparent that it was about much more than that and I also didn’t know didn’t even know that being Jewish was my cultural identity, not my religion, so whether I was religious or not, that was a cultural identity. It wasn’t a religion. The kids taught me that – this is a value system that is Jewish in a way that has to do with empathy and caring for others and fostering values for the next generation.

As I was cutting [the film], I also realized this story about the rivalry really was a metaphor for the divisiveness in our world right now. It was really good timing because [first] it was Trump and then it was COVID and there was a rise in such intolerance and inequality and white supremacy and antisemitism and hate crime, all these things that are happening in our world right now and addressing that in a broader sense became what the movie is really about. Making it, in a way, is my social activism to give voice to that and give permanence to their voices. I think I realized the importance of knowing history in terms of trying to make change now and that there’s some sort of cultural amnesia about these things. Maybe we don’t spend enough time in our culture learning about history because you really aren’t going to know how to affect change unless you look backward and see how it was done in the past. You can’t stop what’s happening unless you have a sense of how we got here and when the film took that direction for me, it was surprising.

“Kinderland” will screen at DOC NYC as part of “The People Vs.” shorts program on November 15th at the Cinepolis Chelsea at 7:15 pm and available virtually through the DOC NYC online platform through November 18th.