When Walker Estes goes to visit a group of men currently incarcerated in the Estelle unit in Huntsville, Texas in “Breaking Silence,” he may not be the type of visitor they usually receive, but he may be the most welcome. A volunteer chaplain at Louisiana State Penitentiary, his stop in Texas is to see his daughter Leslie, but the side trip to Estelle is to give comfort and learn of concerns of those who are deaf, as he is, and serving time. Although society is not often given to thinking about the incarcerated after they’ve been sent away, even less consideration is given to the plight of those with various disabilities, some of which could contribute to why they’ve received time in jail in the first place. As co-directors Amy Bench and Annie Silverstein come to learn from capturing the silent exchange, at least one of the incarcerated didn’t receive an interpreter until the day of his trial, depriving him of the opportunity to understand the charges against him, while another worries what will happen to him in prison when guards may not be able to be warned if there’s a violent attack.

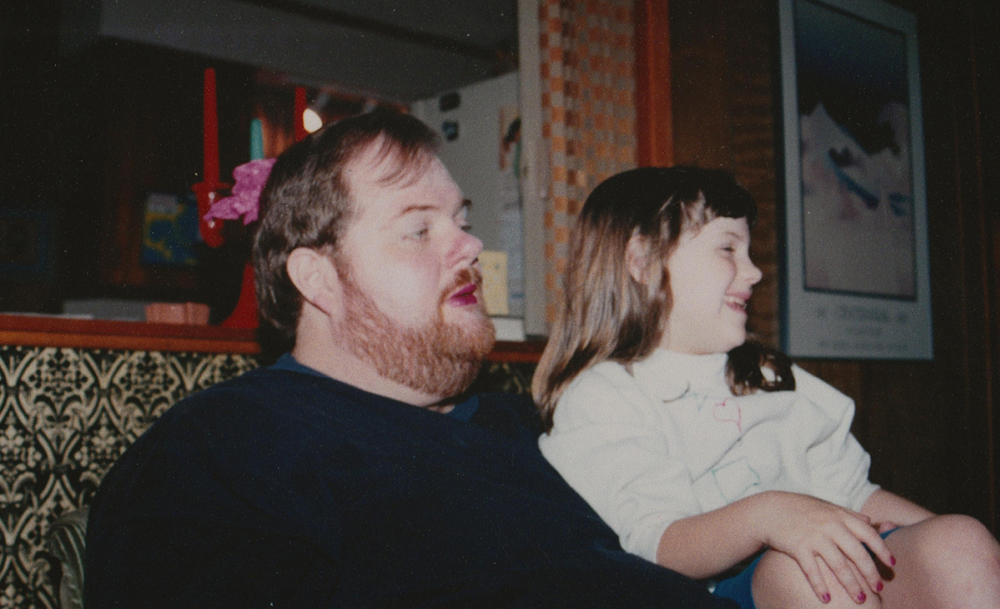

If that were all “Breaking Silence” were able to show, it would be eye-opening, but it aims for the heart as well with two of Austin’s finest filmmakers teaming up for the heartrending story of Walker and Leslie, whose own experience in prison inspired Walker on the path he’s on, though she’s not hard of hearing. Recognizing the difficulty of trying to communicate with his daughter when she doing time, Walker thought of other families and the incarcerated who might have the same issues and wanted to make an excessively lonely experience a little less so. Bench and Silverstein not only trail Walker as he makes the rounds to connect with current and former members of the incarcerated, but reestablishing a relationship with Leslie, who has completed her parole and joins him when she can while also trying to spend more time with her young daughter Analise.

To say the film is deeply compassionate would be an understatement when it looks at injustices in a number of different forms, but most specifically as it applies to communication when issues are raised about what accommodations should be made if there is a standard of humane treatment for prisoners and whether second chances are even possible when people are essentially denied a first. After making SXSW favorites “More Than I Want to Remember” and “Bull” respectively, it is no surprise that Bench and Silverstein have crafted something as emotionally compelling as it is provocative, and with the short making its Texas premiere this week at South By, the two spoke about teaming up and working on how they could most sensitively express themselves with both deaf and hearing audiences in mind.

How did the two of you join forces on this?

Annie Silverstein: We did a lot of research on “Bull” for the character of the mom who’s incarcerated, and when “Bull” was complete, I think both Monique [Walton, the producer] and I felt like there was more work we wanted to do, talking about the prison system in Texas. We’d been bouncing around ideas of actually doing some kind of short doc or an experimental film, something that was different than straight up fiction, and when we heard that Amy was writing this proposal [for ITVS], we talked about [Walker and Leslie], and they sounded fascinating, so it was like, “Oh, we should all work together.” We’re all friends and making films with friends is my dream because we never have time to hang out otherwise, so it was a wonderful way to make work and also spend time with people that I love.

Amy Bench: The film originated with Leslie, who I met via the nonprofit Truth Be Told at the end of 2019, just a few weeks after she was released from prison. We knew that her father was deaf, though we didn’t know how active he was in working with men who were currently and formerly incarcerated at that time. Leslie talked to him daily and still does, sometimes multiple times a day. Walker was really one of Leslie’s lifelines when she got out of prison. She has a great support network, including her sister who invited her into our home when she was released, and then her father who she talked to daily, who was a few hundred miles away in Baton Rouge. We were [initially] really interested in how incarceration impacts families, specifically women. But as we continued to make the film, we got really interested in the work that Walker was doing because we hadn’t really thought about how incarceration affects deaf people. His role in the film grew as we got more involved in capturing [him] working with the men who had been released, and after a couple of years, we got access to a prison, so we were able to join him in one of his sessions that he had with men who are currently incarcerated.

That scene inside the prison actually seems to become the backbone of the film. What was it like to capture?

Amy Bench: That was our very last shoot and it almost felt like a Hail Mary because we thought we’d gotten permission six months prior and then that fell through. The first time we showed up, there was a lockdown because someone had escaped, so this was basically the third attempt to get into a prison and see Walker. We knew that it was going to be powerful to see him connect with men that were incarcerated and deaf because they don’t get a lot of support. That’s the whole reason that he is an advocate and he’s volunteering as a chaplain. It’s his way to advocate because you’re technically not allowed to go in and do what he does, but as a chaplain, he’s able to talk to them about issues that they’re dealing with. So it was always a dream of ours to get in and that scene really grounds people in the work that he does.

Annie Silverstein: Honestly, we didn’t know if we were gonna get access to shoot, so we’re really thankful because it’s such important work he’s doing and we wanted to have at least one scene that shows it.

Amy Bench: It’s the moment where he admits that the work he does is because of Leslie and that he wishes he could have made some different decisions, That’s the emotional crux of the film in that moment – that scene really helps that when he’s talking to these men about why he’s there.

When it’s not your first language, do you become attuned to the subject in a different way when you’re trying to understand what they’re saying?

Amy Bench: As a cinematographer, I have found myself filming in languages that I don’t understand, but I’m attuned to body language, so that is definitely useful because as a documentary director, I think the emotional connection is one of the most important connections between the filmmaker and the participants in the film and I think that comes through whether you speak the same language or not. Filming in ASL, we definitely had to do check-ins before and after each scene just to talk about what might be going on and what the core essence of the scene might be. We did have interpreters for some of the scenes that we filmed, but not all of them. We really left that up to Walker to decide when he was comfortable having an interpreter there.

Was there anything that happened that changed your ideas of what this could be?

Annie Silverstein: There were several reveals for us as filmmakers. The first, of course was Walker’s work and really learning more about huge issues around accessibility for deaf people who are incarcerated. The second reveal for us was realizing that this film, at its heart, is a father-daughter story. Amy and I are both parents, and we could certainly identify with the beautiful, hard, messy relationship that Walker and Leslie have. His love for his daughter and total commitment to her, but also his regrets, and [how] their relationship has had many chapters, and they’ve had ups and downs, but have really worked to understand each other, and get closer because of what they’ve been through. We found their commitment to deepening their understanding of each other, and their relationship very moving.

Amy Bench: The pandemic certainly was a huge challenge to work around and through. We often questioned what this film was going to ultimately be about and how we were going to get there, but we started by doing Zoom interviews [with] Leslie during the pandemic, and then as things opened up a little bit more and people felt safe, we were able to do more in-person interviews and start filming scenes. Finally, after a couple of years, we were able to get into the prisons. We continued to edit through this entire two-year period, always knowing that we wanted to have people emotionally tied to our subject matter and to the participants in the film, but it was a constant evolution. A lot of the advocacy work that Leslie was involved in came to a halt because COVID was traveling so rapidly through the prisons, so those programs are still not up to full speed. Unlike much of the rest of the country and other programs, prison programs and prison access still continues to be more difficult than it was prior to the pandemic. It was a really tricky film to edit, but when we finally made it into the prison and we put those scenes in the film, it really started coming together in ways that we were really excited by.

At one point, you see Leslie go on a visit with Walker to see Dino, who previously served time, and it suggests it’s hardly the first time she’s made the rounds with him. Is she involved in advocacy work as well?

Amy Bench: Leslie currently is working with Truth Be Told, the nonprofit that she participated in about owning your truth and learning to process it. Leslie’s mentioned there are a lot of feelings that come with being an incarcerated woman. There’s a lot of guilt in ways that maybe men don’t face, because you’ve left your child or children, so this organization exists to help women through those feelings and to try to overcome them so that the cycle doesn’t continue to repeat itself. Since being released, Leslie has been a facilitator for that program, but it’s all virtual, so she writes letters to women who are currently incarcerated in much the same way that she participated, but in person, so it’s one reason that you don’t see Leslie on the ground, but again, it’s COVID-related and I think supporting her dad and the work that he does and going to visit some of his friends and clients that he works with is easier for her than stepping foot in prison again. I think she will get there, but I don’t think she’s quite there yet.

It seems so obvious and savvy, but I had never seen anyone do this in a film where you’ll carry dialogue or narration across a scene change with subtitles as one would with a voiceover. Was it much of a decision?

Amy Bench: That was definitely a strong consideration that Annie and I and our producer Monique talked about throughout the editing process– that discussion started before we even began production actually. We did have all of our footage interpreted with voiceover, and then we had a feeling that we were gonna wanna drop the voiceover at some point. We wanted to be able to share the film with audiences who are deaf and once we had a strong rough cut, we wanted to see if treating ASL as you would voiceover would be jarring or if it would make sense because I think traditionally in an ASL film, you would stay on the speaker and then you would cut to the response. But we wanted to see if this film could play differently and cut differently.

Annie Silverstein: It was a really eye-opening process for us. Thankfully, we had wonderful consultants. But we were constantly asking ourselves as hearing directors about issues of accessibility and how do we cut for story? These questions were a constant part of the making of this film, especially in the edit room too, so it wasn’t something that we knew how we were going to handle at first. It was really an evolution.

It seems like there was plenty of thought put into how a hearing audience would experience this when you’re very comfortable sitting in silence at times and it has a really gentle score. What was that like to figure out?

Amy Bench: Yeah, we wanted this film to feel accessible and we wanted the score to reflect the tone of the film. Because there was going to be a lot of ASL, we didn’t want to just paper over that with a bunch of music, and we wanted silence to be a big part of the film as well. So we wanted the score to be powerful, but also subtle and not really lead the viewer into a certain emotion, but support what was going on. Even when we were in the mix, I think our score is mixed a little bit lower than typical films because we wanted it to have that same sensibility as the rest of the film.

Annie Silverstein: Our composer William Ryan Fritch is very attuned to storytelling and to character and the emotional pull of things. I’ve worked with him several times and he really understood that we were looking at the score as a texture versus a driving force of the narrative.

What was the recent premiere like at Big Sky?

Amy Bench: Our unofficial “world premiere” was really in a classroom at Big Sky High School with 25 students, and they really responded so well to the film. We brought Leslie and Walker, and the students had a ton of questions because it shed a light on an issue that they hadn’t really considered. They were really curious about what it was like for Walker to grow up as a deaf person in a hearing family, and what I loved and what we were hoping that would happen with the film is that Leslie and Walker are getting to know each other better even after the film is complete– and maybe even more so now that it’s being shared with others. After the high school screening, Leslie learned that Walker didn’t start learning sign language until he was 15. And it’s a way for them to heal from the trauma they have both experienced in their lives. Walker’s sister, after seeing the film recently, messaged him and said, “I’m so sorry,” because his siblings never learned ASL. He was pretty ostracized from his family, so working on this film with Leslie and opening up about the past I think has a large part to do with his healing.

Even though he’s never been in jail, I think Walker really feels for the men who were imprisoned because he was very angry and upset in his adolescence, which you wouldn’t know from the film, and he’s very proud to be deaf and part of the Deaf culture with a capital D. This work is very healing for him and I think [seeing the reaction of others] really made Walker and Leslie proud of the work that they’re doing and proud of their own relationship. It’s really palpable to see.

“Breaking Silence” will screen at SXSW as part of the Texas Shorts Program at the Rollins Theatre at the Long Center on March 10th at 5 pm and March 14th at 11:30 am.