Of the many passion projects at this year’s Toronto Film Festival, it’s unlikely that any filmmakers poured more blood, sweat and tears into their project than Allison Berg and Frank Keraudren.

“We have like the antibiotics and the urgent care bills to prove it,” jokes Berg, who appears to be relieved to have finally put the finishing touches on “The Dog,” a film 11 years in the making that required no less than five different cinematographers and lists five of its interviewees in a “In Memory Of…” end card.

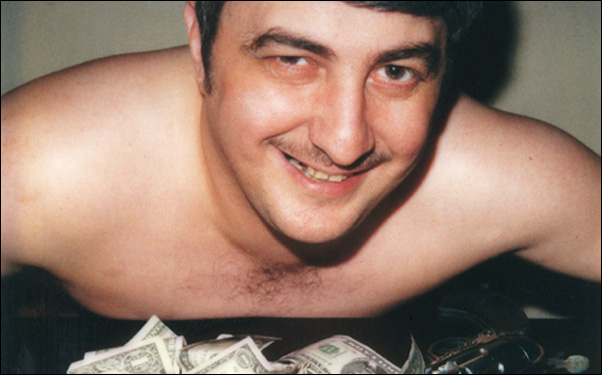

While that may seem like a lot of time and energy to devote to a subject that was already the focus of the ’70s classic “Dog Day Afternoon,” it’s clear from watching “The Dog” that Berg and Keraudren needed that many years to fully get their arms around the whole story of John Wojtowicz, the brash and boisterous would-be bank thief who aimed to pay for a sex change operation for his lover and whose criminal exploits were tame in comparison to the rest of his life.

With cameras rolling for four years before Wojtowicz’s passing in 2006 and seven years after, “The Dog” conveys a story as volatile and magnetic as the man who lived it, tracing Wojtowicz’s journey from being a Goldwater Republican to a McCarthy peacenik, radicalized by his time as a soldier in Vietnam where he not only saw the horrors of war but was first seduced by another man. As John is happy to tell you, four wives and 23 girlfriends followed, just part of a ridiculously overstuffed life in which he became an unlikely key figure in the gay movement of the 1970s (while cruising for men who had just come out), the inspiration for one of the decade’s most memorable films and a force of nature to be reckoned with even as he fights a losing battle with skin cancer.

Berg and Keraudren capture it all with great zeal and while the two were at the Toronto Film Festival, they spoke about how they first met the unpredictable Wotjowicz, why they were compelled to keep going on the self-financed production over the course of a decade and the surprises that were in store for them.

If John passed away in 2006, you’ve spent nearly as much time working on the film without him as you did with him. Was it like making two different movies?

Frank Keraudren: It was.

Allison Berg: The thing that’s hard about editing after someone passes away is you can’t go back, and there were certain things that you wish you could ask him more about. You’ve got what you’ve got. But all of those other interviews you saw, we did all of that after he passed away. There was a lot more work to do, and then for us, trying to find the time to edit something that’s self-financed, there’s a reason why there’s so much time.

FK: But I think, especially when you say about two films, when we were editing after he passed away, once we had all these other interviews and all these other insights, we started showing them to colleagues for feedback and there was that dual element because he was the narrative. He was the guy telling the story, but then you start having these other people in the part that were reflecting upon him. That was a difficult balance to strike because we knew it couldn’t just be a monologue and here’s John, unedited. He antagonized a lot of people and you had to find a way for them to speak about something that happened 30 years ago. Their feelings have changed, and it was very hard to get people to talk about how they felt in the past in the present tense.

How many times did you get to speak to him on camera?

AB: It was two main interviews. He covered his whole life up until the end of the robbery in the first one and his story picks up in the second one, so it had this natural breaking point.

FK: It looks like this epic progression in the movie, but when we were filming it, it just felt more like this is happening. We don’t know how much time there is, we’re just doing whatever we can, and then afterwards, we’d try to make something out of this. It was very much like the story itself. These images and these people are vanishing in front of our own eyes. The New York that we’re depicting doesn’t exist anymore.

As native New Yorkers, was it interesting to go back to that period?

AB: I was a 1970s kid, and I loved that era. Both sides of my family are from Brooklyn and I don’t know if I’ll ever have the opportunity to cover the ’70s New York in this way again. Compared to what New York’s like now – it’s clean, it’s safer, and it’s very corporate – that was definitely one of the best parts of it.

FK: Also, it was very important for us because you find a story like that and your opportunity as a documentary filmmaker is if you can find the images, then you can show it in its real context. The images of New York are not just there to make it look cool, but this is how it was. The images we found of John’s involvement with the gay rights movement are the same. He’s telling you this incredibly fascinating tale, but when you get to see the real images, that’s really exciting.

Obviously, you’ve made a whole film to answer this, but what was so compelling about John’s story that you wanted to invest yourselves in making a film about him?

FK: The easy answer is we love “Dog Day Afternoon.” We thought it was an incredible story and we thought he was coming out of prison at the time that we started, but we miscalculated and realized by researching that he’d been out for decades. Then we met him and initially we could’ve made a film where we could’ve sought out Al Pacino, Sidney Lumet [and others involved with “Dog Day Afternoon”] Then we realized, that’s not the film. John immediately was larger than life and very complex as a personality, had a million stories to tell, and we knew there’s something there. Once you get involved and you live in New York and he lives in New York, it never went away. We stuck with it.

AB: Many times it was probably like falling down the rabbit hole because once you go there with somebody like John, the story kept opening up more as the time went on. We always knew he was bold, but in terms of the subjects, we knew that you come across somebody like John not that often. He’s real. There’s no bullshit with him and he’s a unique New York character, so we felt like he deserved the film.

The exact feeling I had was that this was a movie star waiting for his movie. When you approached him, did it feel that way?

AB: Yeah, but he’s been approached before. He’s difficult and he loves to make people uncomfortable. Right from the get go, we met him and he physically was inappropriate within two seconds and …

I read the interview you gave to Filmmaker Magazine where you said he hit on a production assistant.

AB: He did. He kept everyone a little bit like on guard, but he just had this way about him.

FK: He was charismatic, but it’s difficult to reconcile that with his real personality because he’s also a very, very questionable individual. All his ex-wives and boyfriends he antagonized to the degree that they all disappeared, but then they still say he was charismatic.

At the same time, he was also inappropriate and what was immediately visible was that this guy had no boundaries. That’s why I think when you watch it, it draws you in because on a screen, you can live like that. In your life, it has consequences. He lived his life as if it was a movie, and there’s the movie about him, and it all is melded together in this confusing way.

One of the interesting things someone says in the film is that the “Dog” personality only came out after “Dog Day Afternoon” was released. Was it interesting to imagine what John was like before that?

AB: He was always a very unusual person. His first wife, Carmen, had so many incredible stories — even when she says [in the film], he showed up and he brought two other women on the date and he’s like, “One of you’s going to be my wife” — he already had this big boss personality. That wasn’t created with the film, but I think he got stuck in the notoriety of the film and became the “Dog” character. But a lot of who he was was already there.

FK: Also, if you put it into context, think about him when the movie came out. Here’s a guy who is in a federal prison and he’s basically destroyed his entire life. Suddenly, Al Pacino portrays him in a fantastic movie. If you’re an Italian-American kid from Brooklyn, and this happens to you, especially somebody like with John’s feelings about what he did, he felt validated, I’m sure. It gave him a sense of being somebody that rescued him from where he was. It’s very misguided, clearly, because I don’t think he was able to tell the difference between the film and not being celebrated by it well.

Since this took a decade to make, what kept you invested in it?

AB: I don’t know. We never gave up on it.

FK: When you’re trying to make documentaries, it’s like you go fishing. You find a subject. Sometimes it works. Sometimes it doesn’t. But with this, it never stopped being interesting. Another like really practical way to say it was that, when you’re self-funding you’d get a job for six months and you’d make money then you put it in your movie and you keep doing that, the stakes go up really fast. It’s not necessarily about becoming rich, but you’re truly invested in the most literal way, and you’re like, I have to finish. You cannot afford to just be like, aww, I just did all this for nothing. If this was free of any consequence, personal or financial, we would’ve probably given up.

AB: I recall our favorite shoot day when we first met John’s brother Tony and we went to Coney Island. That was one of those days where we saw another side of John that we’ve never seen before, learning this incredible story of something that happened in his life that you could see greatly affected the way he thinks about things. Then we weren’t planning to go to the bank [that he held up] that day, but he’s like, “Let’s go.” That was just one of those days where we just learned so much and saw so much that we didn’t expect. Days like that keep you going for a year.

FK: But a part of it was that we knew John was a storyteller, and he’d tell crazy stories, some that we knew obviously weren’t true. A lot of the other ones, he would tell you and then they would check out. We also didn’t know in the beginning that he had literally archived his entire life, so when he’s telling you about 1964 and says “I went to the Republican National Convention and I was a Goldwater fan,” you find this little box, and he pulls it out … this is maybe five years after we met the guy, and in it, you’ll have the train ticket, pictures of him on the train with the people he went with, the floor plan of the convention, a can of water that he saved marked “Goldwater.” Nobody keeps this stuff. He had a stash. That was just amazing. It was like seeing a story come alive in front of your eyes. For a documentary filmmaker, that’s like out of a dream.

“The Dog” will open on August 8th in Los Angeles at the Cinefamily and in New York at the IFC Center and Lincoln Center, followed by expansion in the weeks that follow. A full list of theaters and dates can be found here.

Comments 1