For those who have been looking forward to the next work from Alexandre Rockwell for some time, the opening title card of “Sweet Thing” is bound to give some pause, but the slight confusion caused by introducing the writer/director’s latest as “A Film by Adolfo Rollo” is a reminder of when audiences first fell in love with him in the first place.

“I did that partly because I made “In the Soup” and the character’s name was Adolfo Rollo and I thought maybe just I was getting a little bit tired of being Alex Rockwell on one level, like there’s a side of me [where] I teach these students like Chloe Zhao and Shaka King and they go on to win these Academy Awards and everything’s kind of youth-obsessed, so I was thinking, ‘Well, I’m an independent filmmaker from the ‘90s and I don’t want to be that guy anymore,’” says Rockwell, who has been the head of the directing department at NYU Tisch since 2017. “I just want to be who I am and changing, so I thought why not make it an Adolfo Rollo film? That’s a nod and a wink to ‘In the Soup,’ but it was liberating for me to do it as well.”

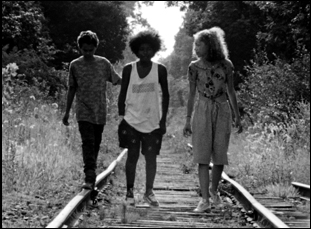

Rockwell may be well past the days of being a struggling artist in the vein of Steve Buscemi’s pretentious auteur in the 1992 comedy that was at the vanguard of the burgeoning American indie movement, but he remains just as creatively restless, a temperament that can be felt in the very fabric of “Sweet Thing” where black-and-white film grain dances as if it’s an extension of his energy. The film is in many ways a follow-up to his 2013 family affair “Little Feet,” in which he recruited his daughter Lana and son Nico to star as city kids who wanted to make their way into nature in a charming adventure, driven by their curiosity and wonder. Six years older when they made “Sweet Thing,” the Rockwells are every bit as mischievous as the pair seeks an escape from their alcoholic father (Will Patton), and with their long estranged mother Eve (Lana and Nico’s real-life mom Karyn Parsons) just hoping to hang on to her new boyfriend, they are largely left to their own devices as they join up with Malik (Jabari Watkins), another kid without anywhere to really call home, to entertain themselves.

There’s a timeless quality to the tale of holding onto innocence as long as possible in a world eager to take it away, not only in either the predominantly monochrome presentation or the fact that Billie is named after Billie Holiday, but the thrill of watching the kids figure things out for themselves as they go, something that was happening behind the camera as well when Rockwell was working with a crew largely comprised of grad students he taught at NYU and taking every opportunity to experiment. While his children could indulge in go-karts and making sundaes for themselves piled high with ice cream and chocolate sauce, the filmmaker could have just as much fun rekindling his passion for the medium and the feeling is infectious when through all their eyes, the world looks new. With the film now out in theaters after premiering just before the pandemic took hold at last year’s Berlinale where it picked up a Crystal Bear, Rockwell spoke about why the film feels so alive and working with his family, as well as how to make the most out of a modest budget and the surprises filming had in store for him.

I made “Little Feet” as a reaction to trying to find my compass again with filmmaking. I just decided to scrape away all the stuff I didn’t really care for in terms of the industry or the career aspect of filmmaking and focus on what I love to do and what I love most about the medium, which I always say kind of saved my life at a certain point. So I made [“Little Feet”] with my kids and I made it in black-and-white and I made it like a ridiculous length, which was like an hour long, and I really had no ambition for it in terms of the market. But the film did quite well. People responded to it, and it was a revelation after the fact to me that I was doing something right by doing something that I loved.

After that, I had another project that I was writing for a couple of years and then I said, you know what? I’m kind of interested in doing the next chapter in these kids’ lives. One was a celebration of when they were living in the poetry of young childhood with all its challenges, [and had this set-up of] one day lasting for eternity and then I thought “What’s the next stage? When do they come up against the adult world in all its difficulty?” So I wrote another script that I really loved and I decided to put it together with my graduate film students shooting it and got back to extending that thing of doing what I most loved to do.

Now that they’re older, did your kids want to be more involved?

It’s funny because “Little Feet,” it’s like I got down on my hands and knees, down on their level and I just observed them because I knew instinctually that I couldn’t force them into some kind of performance. I had to be present with them and make a very simple narrative, like a road trip, but they’re actually walking [around] with a grocery cart. It’s a sidewalk story. So it’s very, very basic, so I was observing mostly and [with “Sweet Thing,”] I’ve upped the stakes a little bit. There’s lines, there’s a narrative, there are beats that they have to hit dramatically and I really didn’t know if they could do it. My wife Karyn and I spoke about “Am I doing something irresponsible as a father?” I know as a filmmaker I’m doing something interesting, but what if it’s a failure? It’s one thing for me to try something and not work potentially, but it’s another thing to put [Lana and Nico] in a situation where [they] might fail.

But [they] rose to the occasion and Lana really collaborated in holding it together, like she’s the soul of the film and the foundation that everything moved off of. She didn’t improvise, but what she did is she kept the other kids on cue. Whenever they’d go off the rails, which was almost something I wanted sometimes, she’d pull them back. Also, I’ve got to tip my hat to Will Patton, who worked so well with her and Nico. He became their second father, practically, and he helped guide them and taught them so much about professionalism and how to respect an actor and respect a performance. I could not have been more fortunate and somehow my instincts were right.

Hands off in a way, but Will just came in with an open heart and he wanted to do this. He’s not a father, so I think it was really interesting for him to play a father, especially a tragic father but who loves his kids, and then Lana and Nico really responded to Will, so I saw that chemistry, and if you see two people who have chemistry, if you ask them to sing a karaoke song together, it’s just going to be interesting, but you’ve got to give them the karaoke song to sing together. You’ve got to give them something to do, so basically what I did was give them things to do and I stepped back because I realized they had the chemistry, so what they were going to do with these givens was going to be interesting, so it was a mixture of giving them guidelines that help them connect and stepping back.

One of my favorite scenes in the film is when the kids are playing with the large scale towing truck like it’s a jungle gym – would you find locations and build scenes around them?

When you make a low budget film, I’ve done enough to know what works when you don’t have a lot of money, a lot of people think [you should] limit your locations, but actually I would say with less money, you should have more locations, but well-figured out, so I got to know the area we shot in and I would spend hours driving around in the car, looking at things I found interesting. When you don’t have a lot of money to make films, one of the things you don’t want to pay for is locations, and if you make movies in Los Angeles or New York or well-known areas, people are hesitant to let you shoot and they want to charge you a lot of money and you’ll just be throwing money at ridiculous things. But a place like New Bedford, they never shoot movies in and I know the area because when I was a kid, we used to go down and spend summers near there.

It’s industrial town that historically, it’s a pretty interesting area – everything from Melville to Frederick Douglass — and it’s an important seaport, but the industry got sapped, so there’s a lot of unemployed people and there’s a lot of structures that are decaying, a lot of factories. I didn’t get any permits to shoot in these places, but I would shoot in these places because they were like Roman ruins and it would just be this kind of industrial wasteland that we could invent our own narrative in. Behind this one old factory, I found this old car tow and an old dock where they had these old shipping lanes and these old railroad tracks and I thought these are priceless settings. It’s funny you like that scene because that’s one of my favorite sequences is when they steal the car and they’re driving around the back of this factory and then they’re out there with the turtle on the rocks. So I look for these locations and I almost feel like they’re as important as characters in the film.

Yeah, we were looking forever because I knew I wanted a surprise element in the film. There’s a little bit of a “Badlands” feeling — and ”Little Feet” has it where there’s the third kid that shows up and disrupts the pattern of their lives — and this kid came [into the story] and I was thinking this kid has got to be a real firecracker. He’s got to be somebody who’s charismatic, full of life and he’s just got to come in and wake them up and bring them back into their childlike, youthful power, to enable them again to be imaginative and free. So I was looking everywhere. Finding child actors is not easy, especially when you don’t have a lot of money and most of the actors are pretty precocious and a little annoying. So I started looking other places. I would find these kids in playgrounds and Jabari just stood out. He was this unbelievably charismatic person, just wild and uncontrolled like a flame. I knew there was a danger that he wouldn’t necessarily be a professional, meaning he’d be a little out of control, but I was willing to take that risk. He really was a wild force of nature who opened up the film in a whole different way, so I’m really happy I found him.

Was there anything you may not have anticipated during filming, but it made it into the film and you really like about it now?

The way I make films now it’s almost like setting traps. I’m hunting for moments that have vitality in them, so often times I’m inviting the audience into the unknown. Actually, an example of a scene I love, [though] I know it may be weird for some people [is] where this man who works with the father — they’re Santa Clauses who work around Christmastime for the Salvation Army, which a lot of alcoholics do — comes by and they’re going to ring a bell and make a few bucks as Salvation Army Santas. I wanted this guy to come over and to kind of flirt inappropriately with Lana and I wanted Will to usher him out of the house, just kick him out [of their house]. I wanted the guy to be a tough guy, and I found a homeless guy on the streets of New Bedford [who was] a frightening, toothless character and I thought, “Okay, maybe I’ll get this guy because he’s real.”

I found him and I gave him $50 and said, “If you show up [on the day of shooting], I’ll give you another $50.” He ended up coming over and I put a Santa suit on him and he was so nervous, he was dripping in sweat and Will Patton did a scene with him. The guy ran away, so Will had to do half the scene without the guy around, but he had this kinetic, bizarre energy that was just like totally different than what I thought it would be and was just incredible, so it was really surprising to me and I thought it was better than what I had written, so I went that way. But there were a lot of wonderful surprises. There’s a whole scene where they’re shooting fireworks at each other on the beach and who knows where that would’ve gone, but I love doing that kind of thing because it’s kind of dangerous, and the kids get excited and it’s like capturing a wild animal. It has a great cinematic quality to it.

Yeah, one of the things I’ve been really happy about is I’ve been able to bring film back at NYU Graduate Film Program. For a while, people were really trying to phase film out, but I pushed to keep Kodak alive and keep students shooting on film and they love it. It’s like vinyl records, [which] have a quality that’s very interesting vis a vis digital music and it’s the same with film. There’s something about celluloid that is very organic with the grain structure. It’s like sand. It has no pattern to it like digital photography. So that’s a wonderful part of it, and black and white is really good for low-budget filmmaking and for that matter, we always look at art photographs in black and white and we have no problem, so why not films? And what I loved about working with the graduate students is their complete willingness to take chances and to break rules. I took advantage of their youthful enthusiasm to do impossible things and I love the fact that they’re not jaded and they’re not saying, “Oh, the way it should be done.” They’re trying to invent a way to do it, so nothing’s impossible, so that was really wonderful to convey that irreverence from my generation to them and I think they responded in kind.

These films must be particularly meaningful when you can look back on them and you have these time capsules of your kids at a certain age and the experience involves the students you teach. What’s it like having them?

It’s such a gift to be able to see my children, who I obviously adore. They’re amazing, they’re little miracles in their own ways… even though they can be a pain in the ass. [laughs] And I haven’t had enough distance with “Sweet Thing,” although Nico’s already grown six inches [since making it], but with “Little Feet, I felt I caught this magical time that is in my memory when all of a sudden, I’d listen to them and they’d be in the other room and playing a game and I’d go near the door to listen to what strange little logic [they had] and what weird poetry was running out of their mouths. Once I was listening to Nico from the other room and he had his head on Lana’s stomach and they were just resting and he said, “I love you Lana in my heart and in my brains” and I just heard him say that and I thought, “That’s just a wonderful line,” so I put that in the movie. And I was just capturing these little moments and it is amazing to see my children in this little time capsule, the poetry and magic of that moment in their lives. I’m sure I’ll feel that way towards “Sweet Thing” as well, that it caught them at a moment I’d love to hold onto.

“Sweet Thing” opens on June 18th in limited release in New York at the IFC Center, Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal and Philadelphia at the PFS Bourse Theater and will expand on June 25th to Arabi, Louisiana at the Zeitgeist Theatre and Albuquerque, New Mexico at the Guild Cinema. It is also available as a virtual cinema release, supporting your local arthouse. A full list of theaters is here.