When AKIZ was in the process of securing financing for his first film, it wasn’t the easiest proposition for potential backers.

“People told me they didn’t even know how to hold the script or read it backward or forward, because it didn’t make sense,” says the German sculptor-turned-filmmaker who is every bit as mischievous as the famed admirers of his work David Lynch and Banksy.

Then again, it wouldn’t be an AKIZ project if “Der Nachtmahr” had followed a typical route to the screen. Admitting proudly that “E.T.” was the second film he ever saw, subsequently followed by a steady diet of Andrei Tarkovsky, Jan Svankmajer, and the Brothers Quay, there are clear cinematic influences on what AKIZ has done as a first-time writer/director, but there is plenty of room for his own crazy ideas in the coming-of-age story of a young woman named Tina (Carolyn Genzkow) who encounters an alien that is every bit the outsider that she feels she is in her small German town. But rather than fear this creature, which naturally she does at first, she begins to embrace it as almost an extension of her id, following the unexpected advice of the therapist who suggests trying to talk to it, despite the fact that she’s the only one who can see it.

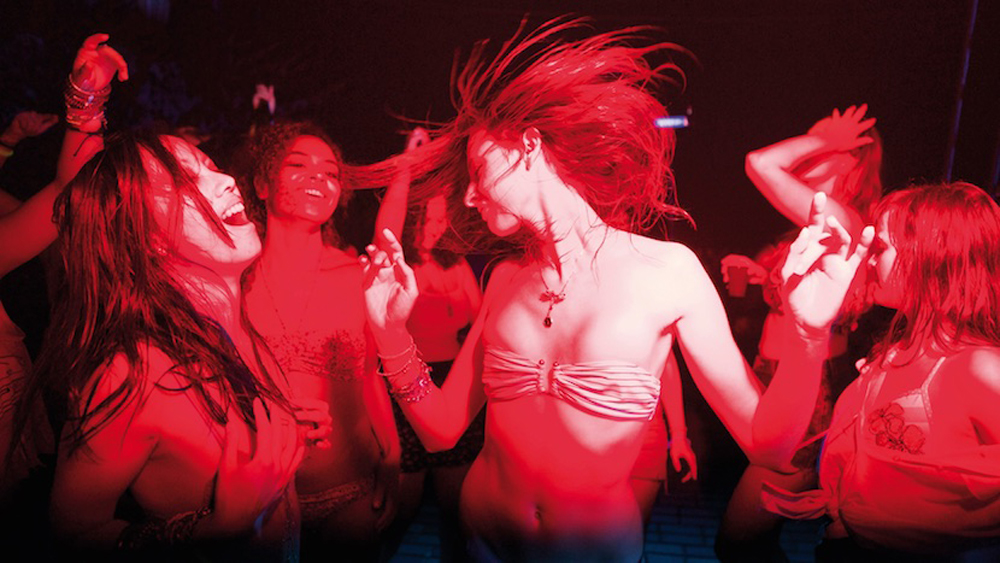

It isn’t as much of a stretch as one might think to compare the film to “Apocalypse Now,” as AKIZ does, witnessing Tina go through a Colonel Kurtz-like meltdown as she futilely attempts to convince others that she’s not just seeing things as well as getting others, including her parents, to actually see her as well. In the context that teenagerdom is a battlefield, AKIZ fills the war with explosions, opening with a rave for the ages and laying the groundwork for one combustible situation after another accentuated by choice techno music, eerily effective sound design and a skewed perspective that turns a fairly traditional premise on its ear.

Just before “Der Nachtmahr” premiered at the Toronto Film Festival, the multidisciplinary artist spoke about bringing all of his different creative skills to bear on his debut feature, translating his dreams into something more tangible in cinema and how Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon ended up in “Der Nachtmahr” as an English Lit teacher.

I did not have the intention to make a film at the very beginning. I thought I’d just make a statue out of stone, a mixture between a very old man and a fetus. Throughout the years, it evolved into a creature that could move and it took me quite some time because I built it by myself. After a couple of years, I had bunch of notes and scenes, then I just put them in the right order to find like a connection between them. I thought that would be a great film. In two or three weeks, I wrote it down and that was it.

You’ve said you first started working on the creature in 2004. What was it about the idea that you kept coming back to it?

Actually, I don’t know, but when I had first the statue in stone, I was living at that time in Los Angeles — this area between society, right in the middle of the industrial area and the desert, and I was always interested as a kid in this particular point. I thought I could put this creature in between these two areas and take photos, and that was just the beginning. I also was just intrigued by this idea of a creature which looks like very, very young and very, very old at the same time.

When I read my notes [back] — because when you write down a dream in the night and the next morning you see it, you go like, “This is my writing, obviously, but I have no idea what that means and it meant something to you while you were writing it down — they felt like a diary from different person talking about the same issue. Then this friend of mine saw all my scribbles and all the other stuff that I did and told me that I’m constantly telling the same story about a demon that has an encounter with society and turns everything upside down. Then I thought it would be great to write all these three great, big projects that I have into a trilogy. [“Der Nachtmahr”] would be the first about birth. The second one is about this creature becoming a human being and becoming addicted to being human. The third one is obviously death.

How did the opening scene come about? It thrusts you directly into the action with this party.

I grew up in the middle of nowhere somewhere in the south of Germany and you get bored pretty quickly, so that’s how we spent our nights. The very, very first idea I had after I accomplished this creature was [to see it] driving in a car with the girl. I thought I would just do this little short piece, and it’s funny that [the initial idea is] basically the beginning and the end now and all the rest of the scenes came to my mind later on.

We did the film for a hundred thousand Euros, which is nothing because nobody really understood the screenplay. [The film] has a logic — a very strict logic — but hopefully, as a viewer, you’re losing the ability to really know exactly what’s going on, and like in a dream, you know that there’s an inner logic, and you have to let go in the beginning. So the scene at the beginning when the car accident is happening is a Rorschach test. Ether the audience [says] “I’m leaving the cinema because this is not my thing” or I’m letting go and see what’s coming because that’s the quintessence of an artist for me. I like films that challenge me, and give me the opportunity to come up with my own interpretation of what’s going on, what it means for me. The first [version of the creature] actually was too obvious. My agent said, for her, it symbolized bulimia? — it’s eating all the time, [Tina’s] throwing up, and I took those scenes out because that was not my intention to make a film about bulimia. Another one was pregnancy. I always was interested in leaving it open for the audience.

When the therapist tells her that maybe she should talk to the creature —I’ve never seen that before.

Actually, I think that’s not so stupid. I have never been to a psychiatrist, I have no idea of what that goes like, but it was important to never show a villain, or pinpoint somebody as the problem, like the parents, the friends or the psychiatrist. I always wanted everybody react in a way that they think they’re right. As a psychiatrist, if there’s a girl telling me stories, and obviously you can’t believe it, your only explanation is it must be in the mind of this girl, it’s not real, so I think I would tell her, don’t run away.

One of the very first lucid dreams that I had as a kid, I was chased by some dark people, like shadows. I hid inside of a bathroom at school, then they came and I watched them. When I realized this is a dream, I felt like, “Okay, what do you want to do? This is just a dream.” Then I flew away. What people say is the biggest fear is the fear of the unknown. Once you focus on something, or you give a name to something, then the primal fear is gone, so that was why the psychiatrist comes up with this idea.

The medium of film? This is it, man. This is it. This is the most advanced, most complex discipline of all disciplines. You have the sound, the image, the story, the timeline. In a painting, as a viewer you decide for yourself [how long you’ll look at something]. Half a minute is a pretty long time if you watch a painting. Two minutes feels like an eternity. [Having] the attention of somebody for two hours, sitting in a dark room, cell phone off, not talking to anybody, just watching one direction, it’s not happening elsewhere. Maybe in the church. Even at a concert, you move, you smoke a cigarette, you have a beer. But sitting there, just watching? I feel flattered and honored to have this attention and people only do that in the movies.

You actually are able to capture that idea of being in between visually in the way that it’s the perspective of Tina, and yet you feel everything around her…

Yeah, the wide angle, I love that. That was not a concept, it’s just the way I see life. When I watch films, I see the normal, regular lenses and I feel like I’m looking through a telescope glass. It’s too remote for me. I had actually a hard time finding [cinematographers] who were willing to shoot this with me. You do not see it very often, and I think it’s coming more and more, because of this Go Pro vision that’s becoming more of that kind of vision.

You make this one cohesive experience with the music and editing, in particular. Did you know what kind of music you’d have before getting to that place in post-production?

Obviously, the party scenes we needed to have music on location [for], but it was different hip-hop music they put on because the kind [we put in later], when you hear it for several hours, people faint and get exhausted. Since I was editing by myself, I had the sounds on the very first day and I already put music on it, just to get a feel for how it works. The editing and the sound went hand-in-hand at the same time. Some tracks already existed, some were created for this film. Some of them I did by myself. I wouldn’t consider myself a techno fan, but this is [set in] Germany and this is authentic sound that’s coming from Berlin. As somebody who’s listening to it, it also puts you in a certain state of mind because it’s so repetitive, it’s almost minimal and that was important for me — to not illustrate the images [with the music], but suck you in as a viewer. That’s what techno does, and that’s why teenagers love that kind of music.

That was seriously difficult. Everything else came easy with these electronic frequencies, [but for the creature], we tested everything. It was difficult to come up with a sound that is not necessarily the typical horror monster sound. At the same time, it should fit a creature which is that kind of size. I wasn’t prepared for that, with the sound you can hear — just the sound — you can tell if it’s coming out of the mouth with teeth or no teeth. You never see teeth, so we tried the sound of babies and it didn’t work. I recorded my own stomach after I ate. It was really, really difficult. We didn’t really electronically modify it. In the end, we had a mixture between these little bears with white eyes and a kookaburra.

Was there any personal significance to you, about the William Blake poem that’s read and that Kim Gordon cameo, in general?

I’ve no idea when I first read the work of William Blake, but it shook me so heavily. And the reason why this scene is in this film is because of Kim Gordon. I met her and I realized that she saw my first film and was interested in it, so we had the idea of working together. But there was a problem because there was no English-speaking adult in this film. There was a teacher who teaches biology. So I rushed home and changed this biology teacher into an English teacher and now I had the possibility to put William Blake in it, so that came by accident as well. But now it’s a key scene for the whole film.

[The scene] was not so important when you read the script for the first time. It was just a scene where [Tina] comes back and tries to get back into her own world, but the world evolved in it’s own way and friends are not the same as they were before. But with Kim Gordon in the scene, then William Blake, and the idea of doing an interpretation of this poem, “Birth of a Shadow,” I hope you ask yourself [as a viewer], is this film about birth? Is it about death? Now, it’s a crucial point where you come really, really close to the core of this idea of this film.Was it difficult to find an actress to play Tina?

It was. There are great actresses now of that age in Germany, but it wasn’t like that 20 years ago. There are great, great actresses out there, but none of them really could handle [not having someone to play off of]. As an actor, you react off what’s coming from your partner, but with the creature, there’s nothing coming. So I had lots and lots of auditions. They were always great, but with this particular aspect, they escaped into a kind of acting which is like screaming [in a horror movie]. She was the first one who picked it up. I have no idea how she did that, She’s really, really intelligent, and has the ability to fantasize. It was difficult, because you have this creature, and five or six puppeteers [working it on the set]. From your point of view, as an actor, it does not look like a creature. It looks funny, it looks like a joke. But she walked in and instantly, I felt like she’s the one. For me, there’s similarities between her and the creature, [particularly in the eyes]. That was a moment [early on when] that was funny, but I realized that on location when we shot, it was like whoa, whoa, whoa.

“Der Nachtmahr” does not yet have U.S. distribution. It next plays the London Film Festival on October 8th at the

BFI Southbank and October 10th and the Hackney Picturehouse 1.