To anyone else, “Cousins” might’ve been an insurmountable challenge to adapt, but for the trailblazing Maori filmmaker Merata Mita, the cavalcade of shifting perspectives in Patricia Grace’s towering third novel, tracking three women whose family had been torn apart by the New Zealand government’s removal of Maori children from their parents, was hardly intimidating. Upon its publication in 1992, the filmmaker, who had been primarily known for her documentaries, began work with Grace to bring it to the screen, and while she could relish wrestling with the material to translate the lyrical qualities of the author’s work and its evocation of all that had been robbed of the Maori as a result of colonialist policies into cinematic terms, she dealt with the exact same power structures that she was planning to illuminate in the film as finding financing proved impossible, though naturally she put up a noble fight until her passing in 2010.

“When Merata passed away and the project had languished, some signs happened for us to pick it up together and try to get it made,” says Ainsley Gardiner, who along with her co-director Briar Grace-Smith, had been a disciple of Mita and become a force in her own right as a producer on the early films of Taika Waititi and launching her own production company Miss Conception Films with Georgina Wonder.

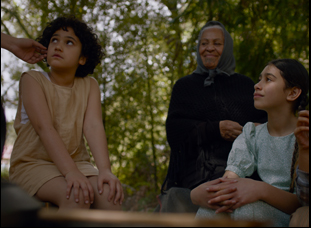

It’s clear from the end result of “Cousins” that its power as a story never wavered, but additionally the film stands now as a testament to Mita’s enduring and ever-growing legacy and the confidence she could instill in those who continue to make films in her wake after highlighting the collective power of the Maori community and their ability to tell stories like no one else. While Gardiner and Grace-Smith clearly steered the ship, they are reluctant to call themselves co-directors even as they shrewdly conceived of a production for the drama that would be as multifaceted in how it was designed as it is in the story it tells, actively engaging the locals of the Ngāti Hinekura and Ngāti Pikiao where they filmed in Rotoiti at Te Waiiti Marae to impress their perspectives onto the film. Quite literally, it is a distinctive view, as the spherical lens that is occasionally deployed to capture the proceedings pulls one closer to the characters while suggesting there is something on the horizon that they can’t quite make out as the absence of Mata, a young girl put up for adoption after being taken from her mother, has affected her relatives Missy and Makareta, even when they may be too young or too far away to be conscious of what exactly they’ve lost.

Built on the foundational Maori belief of whakapapa where blood ties supersede geographical or chronological boundaries, “Cousins” appropriately feels as if it is a single body that draws energy from three separate veins as Makareta renews her search for Mata in the present day as she confronts her own mortality with a cancer diagnosis, and unfolding across decades, it gives shape to how communities of color can be marginalized in profound and largely invisible ways as well as the enormous amount of strength that can be summoned in response if only they can recognize they have it within them. Gardiner and Grace-Smith surely deliver the full force of it, having previously collaborated on the anthology film “Waru,” which saw eight female Maori filmmakers convey the reverberations of the death of a young boy throughout a town, and their latest is bound to make waves across the world, amplified by the ARRAY Releasing, which has made the film available globally on Netflix. On the eve of its release, Gardiner and Grace-Smith kindly took the time to talk about how they carried the torch that their mentor Mita had first set aflame, finding that by honoring Maori storytelling traditions they could bring something fresh to the screen, and paying tribute to the late Nancy Brunning, the New Zealand acting great who had been set to play Makareta in her later years until her own health deteriorated.

Briar Grace-Smith: The way it’s written, it’s like a community is speaking to you and it comes from the POV of various characters — there’s even a character that’s the ghost of someone’s twin who never made it to the world of the living, so that spirallic storytelling is more this way circling rather than going straightforward and picking up stories of community along the way. In terms of our oratory as Maori, our people are great talkers, so [if you] come to our tribal areas, we take you into the meeting house and people stand up and they greet you. It’s also a place where a lot of debate happens, but in terms of the way the speakers operate, they hold in their head something they want to say — a point they want to make — but to that point, they reference the past many times. They weave in and out of past to get to the present and by the end of what they’re saying, what they’re talking about has huge impact, so the book embraced that and it became really important in the film to tell the story in that kind of nonlinear, spirallic kind of narrative.

I sat quite closely with the novelist, who at one time in my life was my mother-in-law, and I read the book about three times and tried to know it enough and hold it in my head so I could own it and think about the things that impacted me in terms of the beats that really stayed with me. It was a process of sometimes truncating story and bringing characters in different locations together. The book’s epic, but to keep the spirit of the book intact even though it changed a lot [was the goal].

Ainsley Gardiner: Yeah, Briar did a great job of collecting all these moments and weaving them together [in the script]. The book itself has all this amazing poetry and imagery and it’s a collection of moments, which I think a life is basically. We talked a lot about the idea of the three girls being in each other’s lives, regardless of if they were physically there or not, so the idea of holding negative space for the missing cousin, or being [embedded] deeply with somebody else’s point of view are the things that informed the ways in which we shot. The nature of weaving, a kind of poetic thing where it’s about the significance of small moments or small details are far more meaningful than necessarily the plot or the drama, capturing the sense of community [were] things that we talked about visualizing that idea of spirallic storytelling.

Ainsley Gardiner: Well, it’s not hard for us [because] it lives in our bones and our bodies and everything around us, so we didn’t have to intellectualize as filmmakers too much how we would present that. What we wanted to focus on as much as anything was not only everything that’s lost, but equally important, everything that’s retained – strength, our community, our connection to land. We attributed elemental qualities that were represented by color in the characters to try to really weave this sense of power that the characters had, so even though this character Mata was in a way lost to [her relatives], in all of that loss and all of that trauma, she still retained a deep sense of connection to those things.

A few years ago, Chelsea Winstanley had told me what an empowering experience “Waru” was just from being able to bring together the community for a film – did it feel the same way on “Cousins”?

Briar Grace-Smith: Yeah, I think the feeling of collaboration we experienced on “Waru” really fueled the desire for Ainsley and I to work together in a different way. On “Waru,” it was often one of the eight women directors would be shooting the film and the other seven or six or five or whoever could be there was there on set to support them and we came from such different film experiences — we traveled with different skills — and that was part of the desire Ainsley and I had in wanting to work together.

Ainsley Gardiner: Part of our funding came from one of my tribal organizations — and one of my criteria, if you would call it that, was that we had to shoot in that area with those people and we had internships for some of those young tribal members, so all of those communities scenes are shot with people from those communities — the aunties in the meeting house, bickering about what they’re going to do with the betrothal – those are all non-actors from that community. That’s a really essential part of indigenous filmmaking is it’s not telling stories about a community, but it’s telling stories on behalf of a community with the community and it’s a real privilege to be able to make films that way.

Ainsley Gardiner: One of the things about “Cousins” is it had a life of its own and a lot of it was by design, but a lot of it was also just guiding a spiritual being on its journey, so I think it happened all the time where we were surprised. It was moving in its own way and the challenge with something like that is still making a film that is engaging. There were a million different ways that film could be put together but ultimately the film made demands of us that we just had to submit to in a funny way, don’t you reckon Briar? The film knew where it was going way more than where we knew where it was going.

Briar Grace-Smith: Yeah, it was really just staying open to the spirit of the thing, especially when you’re shooting and you’re working with a lot of community and you sometimes don’t know what on earth is going to happen, it’s just rolling with it.

From what I understand, Briar had to step in at the last minute to play the older Makareta because the late Nancy Brunning had become too sick to play the part. If you built the role towards her, did it feel like even if she couldn’t be there, you were making her a part of this?

Briar Grace-Smith: In a way, I was. Nancy Brunning was one of my closest friends, so without even thinking about it, I was thinking of the way Nancy had embraced or was talking about the part, but also as a writer, I’d lived with the character for so long I had a feeling of how she walked in the world and the heaviness that she carried in terms of the belief she had to find the missing cousin. When Nancy left us, I was very aware of whose shoes I was filling and that’s what it made it so hard because two weeks before we shot, we realized Nancy was too sick to be able to play the role and we adapted it on her wishes to suit her, so I started to rewrite the script, thinking about Nancy in a wheelchair because at the stage with her cancer she was in a wheelchair.

We had a small window of time where we auditioned other actors [for the part], and something we came up against was finding the right person for that role because we were quite aware that Nancy was the person we had chosen.

Ainsley Gardiner: It was impossible actually and one of the reasons why Briar was the only option was because only she understood and knew the character so well from from having written the character, but also because Nan had left such mighty shoes that actually Briar being so close to Nancy was one of the few people who could actually bring Nancy into the role and still play the role as Briar would and wanted to, but there was just nobody else who could fill her shoes, not because they weren’t great actors, but because of who Nan was at all levels.

Ainsley Gardiner: Getting it out into the world, it happens so long after, it’s like “Cousins” is a teenager now for us. [laughs] We gave birth ages ago. But we were really lucky that we have amazing relationships with indigenous filmmaking communities around the world through our experiences at various film festivals, so we know and have known that “Cousins” as much as it’s for New Zealand and for our people, it’s a film for those communities as well. It speaks to many of the issues that they experience — if you look at the residential schools, the many, many children who have been discovered, murdered and neglected and the same in America with Native communities, we’re just excited to share it with our big global family finally because we know that they’ll be looking forward to it.