In Sophie Huber’s invigorating history “Blue Note Records: Beyond the Notes,” Wayne Shorter can be seen reflecting on a time when he and the other musicians at the legendary jazz label wondered whether their work would be remembered.

“When we were in the studio in the ‘60s, we questioned whether or not what we were doing would be heard twenty years from then,” says Shorter. “Would it create some kind of value? The kind of value you can’t put a price on because we were not in the business of making hit records?”

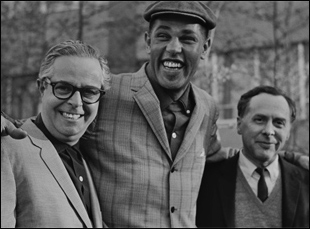

It had not been in the mandate of founders Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff to concern their artists with striving for financial success when they created Blue Note after fleeing Nazi Germany during the 1930s, instead believing there was a sustainable, if not necessarily big, business in recording the artists that they had previously enjoyed from across the Atlantic. After escaping persecution, they wanted to give their musicians the freedom to experiment and while that meant there were obvious markers of financial success to strive towards, it opened the door for the likes of Shorter, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk and Lee Morgan to innovate and often collaborate, creating music that feels as lively and active today as it did when it was first recorded.

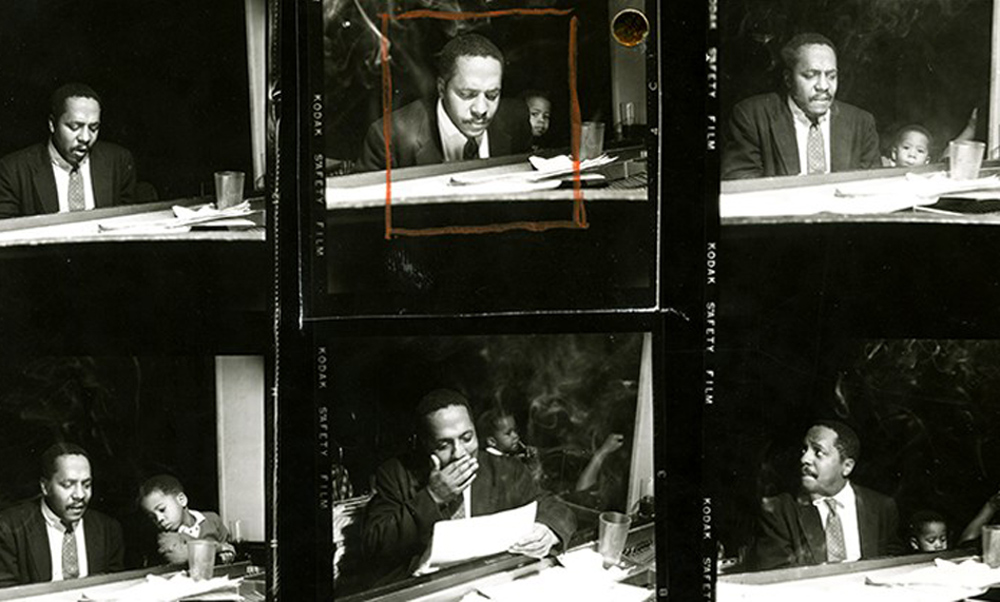

Huber honors this in “Beyond the Notes” by envisioning history as if it were jazz, with musicians and other Blue Note associates such as sound engineer Rudy Van Gelder riffing on their work and the label’s place in the culture while the film reveals a rhythm that persists and repeats itself with new wrinkles to this day, not only in the continual cultural presence of the music and its ongoing influence in the way it was made, but as a way to give voice to the inner city where the musicians were from. After reconsidering how to speak to someone’s entire life while feeling it’s only looking ahead with her last film, the intimate profile “Harry Dean Stanton: Partly Fiction,” the filmmaker seeks out present-day artists who have bridged the gap such as Terrace Martin, a multitalented musician and producer for the likes of Kendrick Lamar and Herbie Hancock, to draw a direct line between jazz and hip-hop, and sits in on a session where Blue Note stalwarts such as Shorter and Hancock are jamming out with current sensations such as Robert Glasper and Marcus Strickland to reflect a sound that remains fresh while every note still carries the weight of everything that came before it.

As “Blue Note Records: Beyond the Notes” rolls into theaters following a festival run that began last year at Tribeca, Huber and Martin extended the conversation beyond the film about the enduring legacy of Blue Note and the musical traditions it established that are taking new forms as they push their way into the present.

Sophie Huber: I did the documentary about Harry Dean Stanton and it became a music documentary – he sings in the film, so I was looking for a label to put out the soundtrack and my friend Poe, a musician, introduced me to Don Was, who’s the president of Blue Note. He loved the film and he actually ended up playing bass on a couple of tracks on the [Harry Dean Stanton] album, and he asked me if I would be interested in making a film about Blue Note and I was looking for a new subject. I had known about the label from an early age, and here we are, it’s the 80th anniversary and we were going to do it for the 75th. [laughs]

It’s a portrait of a company, but still it feels as intimate and personal as the Harry Dean Stanton fi̇lm. Was that daunting to figure out?

Sophie Huber: Yeah, it’s a very different animal because this is about so many people and at the end, it’s a portrait of the label, but I wanted it to be as personal and intimate and human as possible, so I thought the only way to do it is to really focus on the musicians, which is also what the label’s founders [did] – to make them make the story and to keep focusing on the humanity of the music and the need to express and the pain it comes out of, but the joy it creates – whatever it comes out of as a reflection of our time.

I also wanted to tell this story from today’s perspective, so that naturally became a part of it and I thought it would be really important for a younger generation to understand where hip-hop comes from and to lay out this continuum. I hear from people who come see the film [that] it gives a different perspective on hip-hop where they might have prejudice, and younger people learn more about jazz, so it works both ways and it was just really important to show that this music has always shifted and changed. And that’s happening right now, so if you understand what’s happening right now, it might make you understand when [Thelonious] Monk did something very new that a lot of people were unsure of. That’s why Blue Note was the only label that would even record him at that time.

Terrace Martin: When I was in high school, I was listening to a Dizzy Gillespie interview and Dizzy put it in the best perspective for me. He said, “Man, hip hop is the new be-bop.” So when I was in 10th grade, that stuck in my spirit, like if Dizzy says that…and Miles [Davis], his last record was a hip-hop record, so if I’m already a fan of hip-hop and I love [jazz], you mean it’s actually welcoming this? Now I have a place in life. At that point, I didn’t fit in with all the jazzy guys and I didn’t fit in with all the hip-hop hip-hop, so [when] Dizzy said that, I knew where to fit in because he pretty much broke it down. That’s Dizzy Gillespie, one of the creators of bebop, still the most genius, mathematical, soulful music in the whole world.

Terrace Martin: Don Was called me and just mentioned it…

Sophie Huber: Yeah, I started researching Robert [Glasper, the pianist] and then Robert was on “To Pimp a Butterfly” and then I had been listening to some interviews with [Terrace] and Ali Shaheed [Muhammad] and I became interested in him as somebody who’s instrumental in bringing these two – jazz and hip-hop – together, producing for Kendrick Lamar, but also producing for Herbie Hancock and being a musician himself. So I asked Don, could he make an introduction…

Terrace Martin: Yeah, and then they came over to my apartment and I was talking, man. She made it so easy and she was so cool. I forgot the cameras was even on. Her vibe was just so welcoming and open that fuck it, let me give it all to you, so bam, let’s just talk.

You seem to know an awful lot about Blue Note’s history. Was it a label you were interested in from an early age?

Terrace Martin: Yeah, I’m very familiar with the whole Blue Note catalog and that time period of music. I spent years upon years digging into that music and coming up in the household that I came up in, it was just a part of it. If you’re an artist walking in those footsteps, Blue Note is our go-to guide. Those are our point of reference. We don’t have a lot of history books, not as many as I would like on that particular subject, so we have liner notes. That’s the only way we can even tell the language of a lot of things back then. Now, we have YouTube, but [to learn about jazz], it was the Blue Note record – the music, the artwork and the liner notes. Blue Note was one of those labels in general where their album covers display a time where you’re at in your life.

Sophie Huber: It’s too bad this is getting lost with Spotify because on these records, you could listen and read and learn.

It’s really great there’s an entire section of the film devoted to Reed Miles, who designed those minimalist covers. When you have this wealth of materials to draw on, was it difficult to figure out how much to include?

Sophie Huber: Yeah, it’s a lot. It was intimidating because it’s such a well-known label and a landmark. The aesthetics are a big part of it and the timelessness of the design of the album covers, and of course, we had to clear all of that, so there’s limitations of how many we could put in, but we just tried to focus on the iconic records. It’s impossible to put everything in that format of 90 minutes, but my hope is that it will spark people’s interest and they will go and find out about the catalog and go listen to music because at the end, you just have to listen to it, really.

Sophie Huber: Yeah, it was planned that the younger artists – Robert [Glasper], Ambrose [Akinmusire], Derrick [Hodge], Kendrick [Scott], Lionel Loueke, and Marcus Strickland were going to record an all-stars’ album for the 75th anniversary and we were planning to shoot them because we wanted to tell this story through the musicians, so that seemed like a great starting point. Then I saw that Herbie and Wayne [Shorter] were playing around the same time at the Hollywood Bowl, so I asked Don to invite them to join the younger group of musicians. They came the next day, and that’s when they recorded “Masqualero” [a new song written by Wayne Shorter] so the film made all that happen. That to me is the heart of the film.

Terrace Martin: That was a powerful day. I was there that day. And it’s such a beautiful experience when you can work with any of the artists, and the biggest ego in the room is the art. Everybody’s just giving and all their bullshit is off of them and they’re really open vessels. It feels like family in those type of sessions, and even how this whole thing is shot and put together, for me it feels like I’m looking at my family history. I’m looking at my ancestors, and it’s like wow, these people make up a piece of me? That’s what I think a lot of people are going to take from it as well.

Was there anything that came as a surprise, either in making it or watching the final film?

Terrace Martin: Yeah, every time I watch it, I always learn something else and it helps remind me to keep pushing forward because to me, the whole documentary is about breaking through challenges. Hearing all these stories about Blue Note, all these things are used for a bigger message, which is to me break through challenges and if you watch this and are not motivated to try something different, you should check it out again. They tried all that shit and all that shit worked, so I got to keep trying. Everything was out of the box, so it reminds me to stay out of the box – in life in general, not just music. Music is just something we do. We’re humans first. So that’s what I take from it. It’s this great story about Blue Note, but it’s a great self-help story within all that breaking it down – don’t be scared of challenges. These two men tried something with a gang of musicians that were trying things and shifted another culture that was trying things. Everyone was trying.

Sophie Huber: And for me, being in the presence of someone like Terrace…

Terrace Martin: Ah no… [laughs]

Sophie Huber: No, but listen now, to be with Herbie and Wayne and to experience their presence, really in the sense of the word, how present they are, how curious they are, how they’re always searching for new things, they never get lazy. Terrace has that too and it’s incredibly inspiring to me also as a filmmaker to why do I do this? What is the true value? When Wayne says [in the film] he “wanted to create value,” how do I do that? How can I do that with this film? So to be closer to that and personally also to get a better understanding of what it means to be a black young man in America, [which] still I can only imagine, is extremely meaningful.

“Blue Note Records: Beyond the Notes” opens on June 30th in Los Angeles at the Monica Film Center. A full schedule of dates and cities is here.