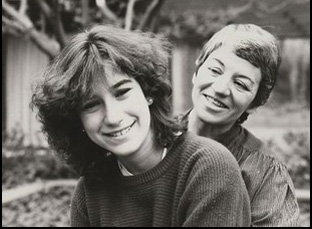

As her mother Ada Karmi-Melamede has often had to do with the buildings she designs, Yael Melamede had to stand back to see what she had constructed with “Ada: My Mother the Architect” to get the totality of it.

“It’s funny, I’ll get an e-mail from somebody who says, ‘I love the film so much. It’s so emotional,’ but then [my mom] will say, ‘What’s emotional about it?’ I don’t think I appreciated how much it would move people emotionally either,” says Melamede. “I did not expect the film to be so personal. Some people think this was a form of therapy or some kind of personal discovery, and that was not the intention, but I think it’s there.”

Both Melamede women had once worked together when Yael aspired to follow in her mother’s footsteps as an architect, but would go on to pursue filmmaking instead and as her stirring portrait of Ada shows, the time they’ve spent together has been limited over the years when Ada’s career led her back to her birthplace of Israel while Yael grew up in New York with her father. The consideration of that space becomes one of many others that Ada ponders in reflecting on a remarkable run professionally in which being denied tenure as a professor led her to establish herself as a premier builder, ultimately earning the bid for the Supreme Court of Israel among other notable national landmarks.

Despite being the daughter of Dov Karmi, a legendary architect in his own right, success was not promised to Ada who appears to have run into many glass ceilings on her way to seeing a way through. Noting that in her style she often digs deeper than ground level for sturdier structures, there is the sense that even as she is loathe to acknowledge it that she had to work a little harder to build a reputation than her male peers, though no less than Frank Gehry is on hand to describe her credibility as undeniable even from an early age. However, Melamede not only honors her mother’s sleek artistic sensibilities with an elegant portrait of her life and work, but by finding the complexities of her experience a part of what gives it such striking dimensions as Ada contemplates how a largely solitary life spent away from her family in Israel contributed to her professional concentration and the director aesthetically often films interviews at different angles and presents them in split-screen to accentuate all the dynamics that Ada had to consider as she went about her career.

Now in her eighties, Ada also has to grapple with what her work stands for in a country that has had so many volatile shifts in cultural and political attitudes over the years, understandably shaken when her designs have emphasized fostering a feeling of community and equality in a place where those values wouldn’t seem to be shared by all. Still, “Ada: My Mother the architect” suggests that her influence will extend for generations to come beyond what she’s been able to put into concrete when so many others have taken lessons from her directly or secondhand and with the film now rolling out into theaters, Melamede spoke about what she took away from learning more about her mother carved out a path for herself, finding the right structure for a complex story and discovering the even greater foundation for the future her mother has laid through the release of the film.

I knew and know my mother really well, but we’d had limited time together over our lives, so this forced me to slow down and really spend some time with her, even on the rides to buildings and back or just occupying the same space more than we have since I was a kid. That was really a special part of the film that I didn’t consider and one of the things people ask me is what did I learn about her that I didn’t know before? And I think I didn’t quite understand lone nature of her journey. People often talk to me about what was it like for you, or they feel bad for me, and I don’t feel bad at all for me. I think I had a lot more company than she had. I think she chose a very singular and difficult road.

You really honor her skills as an architect in the visual design of the film – the interviews have this striking split-screen quality. How did that come about?

That was really by chance. We were feeling a little bit stuck in terms of the film, not finding a distinctive visual quality, and I was working with a fantastic verite cinematographer who at some point happened to be busy, so we needed to find somebody else and we worked with somebody who comes more from the fiction side. At one point, he just said, “How about if we turn the camera 90 degrees?” And he showed me this profile that he’d done and [frankly] I was out of ideas, so I was like, “All right, let’s try it.” But it was beautiful. Then we tried it with two cameras, which is really complicated [with these] big cameras and we had to create special mounts so that we could turn them 90 degrees. But when my editor put both images together, so we could see them at the same time, I really felt like, “I’m so silly. This is so obvious. It’s such an architectural language. How did I not think about this sooner?”

There were things like that that were real serendipity. I love that language. It’s such an expression of architecture in the visual nature of the film and it was perfect for showing my mom, but it’s a little bit of a taxing system, because you want to look at both images and read at the same time and there’s a lot of information to take in, so I felt very strongly we couldn’t do that for the whole film. We could just do it for some special sections and it is funny, people who see the film twice are really happy actually to see it twice, so they get to see other things that they didn’t see the first time. but not everybody’s going to see a film twice.

It was very much a slow burn, trying to figure out what it wanted to be and how to tell it. It was very surprising all along the way. I didn’t think I’d be in it. I thought it would be more chronological. I didn’t think it would be so poetic. A lot of the time it was mysterious. We didn’t have a roadmap. We just started filming and responded to what felt like it was working or most special and the roadmap was “Well, that worked when we last filmed, so let’s try and do more of that.” There was a point where we thought the Supreme Court [building] might be the first chapter of the film and then another important building that she was working on would be at the very end. But that the building that she was supposed to do at the end is the prime minister’s office, which got really entangled in crazy bureaucracy, which could have been a film on its own.

There’s a book that came out a couple of years ago that was made up of chapters, some of which are similar to the ones that are in the final film and as we were grappling with structure, I found the crew all loved this book. They just kept looking at it, and what I love about my mom so much is, and I think [in general of] people who love their work, is that the world’s mysteries are all wrapped up in their work they do. It’s a way of looking at life, not just at architecture. So I thought, “Maybe there’s a way to take these chapters [and adapt them],” and those chapters ended up helping us convey that feeling [that] these aren’t just ideas about architecture, but ideas for life.

One of the things that I thought was really interesting to seize on was the idea of Hebrew and English being split as a language and how that could apply to your own relationship when I imagine you might be more inclined towards English and she would be more towards Hebrew based on where you spent more of your lives. How did that come into play?

Initially thinking more commercially, I wanted the film to be all in English. There were a few days at the beginning where I was saying to [Ada], “Let’s just do this in English,” and I just felt that she is so much more comfortable in Hebrew. But part of our story is a bilingual story, so I just felt like it wasn’t right. Her true self wasn’t coming out, and at the same time, it was great to have her do some English one so people could understand how rich her English and her thoughts in English are. Sometimes she says there are more words in English to talk about architecture than there are in Hebrew, but there’s also such a depth of thought in the way she thinks about Hebrew and the language. It is such an interesting and different language [than English]. I was saying to somebody recently that we often talk about the semantics and how there’s certain words you can’t translate well from one language into another. In Hebrew, there’s actually no real word for subtle and that that’s so perfect because it’s not subtle place. So [acknowledging] the bilingual nature of our relationship helped talk about a lot of issues just naturally — that there’s a divide, that there’s a give and take, that there’s some things lost in translation.

Having spent time with my mother, but also worked with her, I would often like end up helping her translate some of her work and we would talk a lot about architecture. A lot of what she says and what she said in the film was very familiar to me, so that wasn’t a big surprise, but to see other people repeat it and to find traces of it in other places was really beautiful. The fact that Doug had those notebooks was amazing because I imagined that kind of deep thought and poetry around architecture had developed over time and was something that, you know, was more true for her older self, but it was actually really present in her younger self. That was really cool to figure out and to discover that it made such an impact on so many people.

One of the things that’s happened as a result of the film is I’ve been in touch with many more or many of her students have reached out and what I’ve realized is that she really had a cohort and an incredible impact as a teacher. The number of e-mails we’ve gotten that are like, “I’ve meant to send this to you for years and haven’t and I just want you to know you really changed my life,” has been really beautiful. Really feeling that she had that impact of a teacher is a very different impact than the built environment, and it feels really extraordinary.

It’s really great in some ways. For me, my mom is very familiar and so are her achievements in some way and she never takes her achievements very seriously, so maybe I didn’t take them seriously enough either. But to see other people be really in awe of what she did and there are many architects who have built more, but to hear successful architects saying the number of civic institutions that she’s done is so remarkable, it has reset for me a little bit how extraordinary her story has been. At the same time, it’s also heartbreaking. She has sacrificed so much of her life to a place that is really disappointing to her now, and as much as the film is a celebration, I think that sadness is also a real thread in the film. There are a lot of people for whom that thread does not answer their criticism or even hatred, so I think it’s also a very sad portrait of Israel and it’s a mixed blessing in terms of both the joy and the sorrow.

“Ada: My Mother the Architect” opens on May 8th in New York at the Angelika Film Center, where many screenings will be accompanied by Q & As through May 14th, and will have special screenings at the Hamptons Docfest on May 10th, and in Los Angeles on May 15th at the Laemmle Royal and May 17th, 18th and 19th at the Laemmle Glendale, the Laemmle Newhall, the Encino Town Center 5, the Claremont 5 and the Monica Film Center, and May 18th at the Roxie Theater in San Francisco.