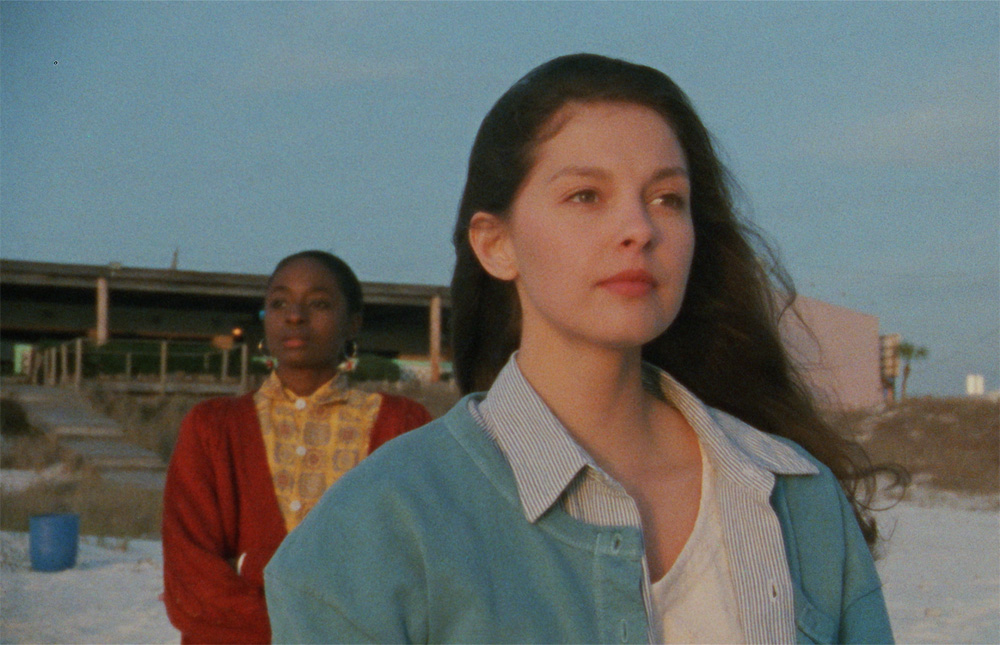

“It’s been a long time since a kiss made my lips hum,” Ruby (Ashley Judd) writes in her journal in “Ruby in Paradise,” besotted after smooching Mike (Todd Field), a seeming rarity in Panama Beach as someone “who could talk your ear off, but listen too,” being just as likely to be found inside curled up with a book as outside in the morning playing the trumpet. He’s worldly in a way Ruby can’t exactly envision for herself, despite catering to tourists from all parts while working in a busy gift shop and while others come and go through town, she feels stuck in place. The same can’t be said for anyone associated with Victor Nunez’s 1993 drama, which launched Judd to movie stardom, made a name for Field, who would find his calling in directing films such as “In the Bedroom” and “Little Children,” and gave traction to its writer/director who exclusively has made films in his native Florida, but shows a rare gift for exploring the vast inner worlds of the people that reside there.

The Sunshine State wasn’t necessarily where Ruby planned to end up, high-tailing it out of Tennessee for reasons Nunez remains vague about throughout the drama, but it becomes a backdrop for some soul-searching as Ruby floats between the affections of two men, the other being the son (Bentley Mitchum) of the gift shop owner (Dorothy Lyman), and the paradox of being surrounded by carefree vacationers without having the financial means to take a break herself. While it’s unfortunate the film hasn’t aged a day in its consideration of the working class and particularly the inequity that leads women to pay the most for the dream of security, “Ruby in Paradise” now has a picture to match after being restored to its original luster for a digital rerelease last year, rectifying one of the more egregious home video disappearing acts of recent memory when the Sundance Grand Jury Prize winner didn’t make it beyond LaserDisc in the U.S.

However, “Ruby in Paradise” can be seen on the big screen this week in New York at the Metrograph where it is part of the series “The Process: A Tribute to Irwin and Robert Young,” and like all the other essential American independent films playing around it, it was finished at the DuArt Lab where Irwin’s dedicated staff pored over every detail of the presentation to make sure that every color in those tropical sunsets off the coast blazed in their radiance as they did when they were filmed. But for Nunez, DuArt was as involved as much at the start of his productions as they were at the end when Irwin’s payment flexibility and generosity towards the filmmakers he worked with would make them possible in the first place and well before the films were blown up from the lower-cost 16mm stock they were shot on to the industry standard 35mm for projection, the filmmakers would leave the lab feeling like a million bucks. In advance of two screenings at the Metrograph this week – one this evening and another on August 21st where Nunez will appear in person, the director took a break from completing “Rachel Hendrix,” his first film in nearly 15 years, to speak about the invaluable contributions Young and DuArt made to his career, the bet on himself that led to making “Ruby,” filming in the frenzy of Spring Break and watching a star being born in Judd.

I’m finishing a film now, and it’s taking longer than any other one because it’s a very limited budget and it’s my first digital one, and walking home a couple of nights ago, I thought, this is the example right here — I don’t have DuArt and Irwin, because that was a way that you got a movie done. There was Irwin and his generous spirit and sense of humor saying, “Bring these things in.” There was wonderful colorists and we figured out how to mix, so this was the first film I’ve ever done that didn’t have Irwin there, and it’s been interesting. We’ll survive and we’ll make it, in part because of all the things we learned in the course of working [with DuArt].

But I had a very deep connection. “Gal Young ‘Un,” [DuArt] didn’t actually process it, but if you go back to the New York Film Festival and had an independent film in that time, [I was told] “Now you’re probably going to get a meeting from Irwin.” And I didn’t quite know what they meant, but after the [screening] was over, this voice shouted out, “Victor!” and I saw this incredibly tall, well-dressed gentleman walk across and down a couple of aisles and say, “Hi, I want to blow up your film.” It was completely new to me that you could even do that. But “Northern Lights” had good fortune at Cannes the year or so before, and Irwin had gotten involved, and he knew that his brother [Robert] was doing 16mm films, [so he asked] “How do we make an optical printer that makes these look good in the “real world”? So a liquid gate optical printer was what was at the mechanical heart of what DuArt and Irwin did for all of these films for decades. It was very exciting, independent filmmakers came from all over the place and the glorious mantra was strength and diversity.

Did knowing you could shoot 16 and it would be ultimately blown up to 35 something that impacted your style of filmmaking? You’ve shot the majority of your films on 16mm.

I shot “Gal Young ‘Un” on regular 16 and of course, when you don’t make a movie for every five, to eight, or 10 years, Kodak kept getting better film, so by the time I did “A Flash of Green” ten years later, I remember going to New York and innocently running into Irwin in someplace and saying, “Are you all still doing Super 16?” because I just didn’t know. And he’s like, “Of course, you should see what we’re doing now.” I presented him what I had hoped to do with this movie, and I said [to Irwin], “I think I’ve got the money to get to Cannes, [but] would you be able to deal with the transitional period between finishing it and getting money back”? And [Irwin] said, of course, so we paid some [but not all of the costs associated with post-production upfront], and we got to make the film in a timely fashion. I’m sure that some version of the story I’ve just told you would probably be something that everybody that’s screening at the Metrograph and a lot more would be able to tell you.

And from what I understand, you could only make “Ruby” after putting up a family inheritance. How did you give yourself the green light for it?

Basically, I was like a part-time worker, and John D. MacDonald, who wrote the story for “A Flash of Green” had a character Travis McGee, who as a detective was often out of work, so he decided to view it as taking his retirement as he went along. I always liked that theme, and this money came from a great aunt, who gets a thank you at the end of the credits, and it was distributed among her heirs — $400,000 is what it was, so I figured, “Okay, if I completely flop as a human being, at least there’ll be money for my son to go to college.” It took a very, very long time to make the decision.

Jim Stark, a wonderful, crazy [producer] that I’ve known forever and we’ve never actually worked together, called me out of the [blue] and said, “What are you doing? What’s happening?” and I said, “Well, I have this script.” This was the second wave of feminism, and I said, “It’s a woman’s story…” and [I thought] nobody’s interested in the working class shopping clerk in the coast of Florida, but I had a lot of interesting experiences coming to New York, and I thought, the thing to do with Ruby is, she is encountering everything that’s discussed big, in terms of the discourse at the time, but she’s a person who has no knowledge of that dialogue, so she has to figure it out for herself. And [Jim] said, “Victor, you should just make it, you’ve shown that you can make a movie for practically no money. You can do anything.” And it was really the timing of that call, around the holidays, and I said, “Okay, that’s what I’m going to do.” This [inheritance] was a gift and I don’t take any credit for the fact that I had this opportunity, but hopefully I used it well.

Seeing it when I was much younger, I wasn’t aware of the literary influences, but now I can appreciate the many that are nodded to here. How did “Northanger Abbey,” in particular, become a reference?

Actually, I’m glad you brought that up because it’s kind of the other way around. There had been so many things based on Jane Austen, and my wife was a big fan, so I listened and heard, both over her shoulder and then directly from her, and we read all of Jane Austen one summer out loud, and it was just a revelation. So I never thought that this was a version or a loosely based on Jane Austen, but when it came in the script [for] that whole scene with Mike [in his library], all of my reading that I had done with Cynthia came [because like me] this was somebody who’s not encountered any of this, but she experiences Jane Austen, and from that, she makes her own interpretation of what it means and [how it] relates to her life. It was like the Emily Dickinson quote, these were things that grew out of writing the story. Sometimes it’s “Northanger Abbey,” sometimes it’s “Mansfield Park,” and I love that scene, and what Ruby says about it as she’s reading it [as] somebody who possibly read “Great Expectations” as a requirement in high school, and obviously she’s very smart, but she’s reading in a language that’s different [now] and she recognizes what’s going on.

If it was influenced, it was part of this whole wave of everything that was going on right now. I was reading in a lot of different directions and I had this experience with “Gal Young ‘Un,” which came out in the ’70s and was based on a short story about a widow, and at the Flaherty Film Festival, two young, very radical individuals [spoke out to say] “How dare you, a man, make a movie about a woman,” and fortunately, the group of the seminar members eloquently gave a defense of the film, but I was very aware even then at the issue. There’s a book by Wendy Lesser, in which she talks about how even in the face of feminism, there are cases when men can make interesting observations, and in fact Ruby Lee Gissing is named after [George] Gissing, who was such a writer in England at the time, and one of the people that Wendy Lesser talks about. And what I’d like to believe is that I’m not trying to pitch a duality here, but more of a continuum of emotions and feelings that if we didn’t share certain things, we wouldn’t be able to understand what we don’t share.

I had worked with Judy Courtney, the casting director that cast “A Flash of Green,” and she’s the reason that it has Ed Harris, Blair Brown, Richard Jordan, and all of these wonderful New York actors. She had moved to L.A. and I said, “Judy, I have no money, it’s going to be a low budget minimum.” and she put out the call and fortunately, we had a lot of young people come by. We cast everybody out as somewhere in the valley, and we thought we had seen everybody, but Judy got a call from Ashley’s agent, and she said, “You’ve got to see Ashley.” She came in and she was nice and she was kind of a bit in a cloud and I was in a bit of a cloud. She had been out of town — that was the reason she was late, and [people around the production] were pushing someone else, very strongly, and I kept having reservations, so we were just talking and Ashley left, and what was interesting to me was you talk for 20 minutes, but we met the next day and I remember just saying [to myself], “Okay, one [actor] may know something more, but what Ashley knows — it’s in her pores — is about growing up in the South. That was it. I, of course, never looked back.

On the first day [of the production], we were shooting all these little short montage scenes, and there was one little brief moment when she comes out of the store, she’s looking for work and is being rejected everywhere, and the sun was setting, and she just absolutely feels broken. The scene ran for 45 seconds, and we only got to use 20 of it, but when we were through, I went over and I said, “Ashley, that’s Ruby, if you can remember what you were going through and doing in that moment, you got it.” And she did, so it was always about what a beautiful, magnetic presence Ashley was and is.

You threw her and Allison Dean right into the mix of Spring Break in Panama City. Were those crazy days of shooting and had the place changed since you last been there in your youth?

What’s strange to me is I remember making this film and laughing because I’m actually Ashley’s mom’s age, and when I was making the film, I realized I now know the meaning of a swan song because everything about that movie was about a certain state and time, and getting to say farewell to it. I grew up in Tallahassee, Florida, so it was a 90-mile drive, it was a special event to go to Panama City. What popped up when I was looking for a script to write was just, here we are celebrating the beach, this is an escape, and you go into a store to buy some suntan lotion or usually there are young people working in the back of this place. What would it be like to have been that person? That was the genesis.

And I remember when we were shooting the spring break sequences, it poured down rain, and I was walking down out of the car and there were about eight kids hunkered down with ponchos, rain gear on, in the rain, and they were marching. Together they were saying, “It’s spring break, we’re having fun!” down in the pouring rain. And I wondered, how could I put that in? That obviously was a different movie, but I’ve always seen those places from the side — I was too old, [but I wanted to include] at least some of that moment of what it was to be young in America, and pre-AIDS, pre-all of this stuff, [where] you were wild and free.

Charlie Engstrom and I just wrapped this movie [“Rachel Hendrix”] about two months ago, and he’s done the score for every movie I’ve made from “Gal Young ‘Un” through “A Flash of Green,” and I agree with you, he nailed this one. And I was so lucky [with the soundtrack for the film], driving to the editing room one day, trying to figure out how are we going to open this film and I’m listening to the college radio station and Sam Phillips comes on with “Raised on Promises.” I just stopped my car and listened to the song, and at that time, [I thought] no way am I going to get a song like that. But it turned out that the sound designer was also a bass player, and he knew a friend who knew a friend who knew T- Bone Burnett, Sam Phillips’ husband at the time.

There was only one screening room in LA that still played Super 16 – it was on the Warner Bros. lot, and I took the picture, and the interlock sound, and set it up, and there was one person invited to see it, which was Sam Phillips. It was another one of those little miracles [where] after the movie, she said, “Of course, you can have the song” and we actually got to have two songs produced by T-Bone Burnett, gloriously sung by Sam Phillips and all of the other songs were by local bands, and then of course, Charlie’s music just glued the whole thing together.

That seems like a testament as well to DuArt when after the blowup process, “Ruby” could be shown in theaters across the country. And as I understand it, you still keep in touch with some of them. Tim Spitzer actually worked on the restoration of “Ruby.”

Remember that optical gate printer I mentioned? Tim was one of the engineers who ran that – him and David Leitner. Tim was not there when we did the first two restorations, but when we did at Goldcrest, he was there, so it felt like a small world and Tim is just a wonderful person and very generous. Certainly, he was wonderful to have that connection after all those years to help restore the movies. And you’re always looking for the great man, but one of the things a great man does is he assembles an amazing, great team, and Irwin had this amazing ability to get people who really cared as much as he did about these films.

“Ruby in Paradise” will screen at the Metrograph on August 17th at 5 pm and August 21st at 6:45 pm, followed by a Q & A with Victor Nunez.