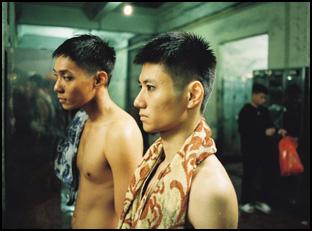

There’s an almost imperceptible divide between nearly everything in “Viet and Nam,” Trương Minh Quý’s engrossing drama about a pair of coal miners, played by Thanh Hai Pham and Duy Bao Dinh Dao, who spend their days going into the depths of the earth. Having previously made a number of nonfiction films that increasingly flirted with dramatic techniques, the director makes his first drama that nonetheless blurs a line between reality and fiction as he casts nonprofessionals and returns to sites where unidentified bodies are thought to have resided since the war, as one of the men searches for the whereabouts of his father when his mother (Viet Tung Le) has never entirely given up hope that he might still be alive. When the family has lived in limbo, continued to be gripped by the past as they carry on a life that will forever be haunted by the absence of their patriarch, distinctions of time and space have become abstract and Quý considered ways in which he could visually express a feeling throughout of being so close to something that was at the same time unreachable.

“Every detail is this kind of visual story, but at the same time, it has to be realistic,” said Quý, who realized there was a simple solution that was readily available. “I think the plastic wrap is beautiful in itself. It’s transparent. We can see through. But I think it’s also a strong and poetic material because we know that it’s associated with death — how we cover the dead body. So we have a house wrapped in plastic [to feel untouched] and we don’t see it, but we know that to cross the borders at certain points, they have to cover their head with plastic [to avoid detection].”

It’s an elegant solution that’s one of many in the bewitching drama where the arresting sight of a man curled up inside a translucent bag can bring to mind both the thought of body bags used during the war and also an embryo waiting to be born. The way Quy finds dual purpose throughout in seemingly mundane imagery becomes part of how he casts a spell when the two miners may have been laid low by circumstance, but find comfort in each other’s arms, making the spoils of the black coal around them gleam as if they’ve unlocked the secret to the universe by finding their place in it. (So intertwined are the couple that the director never names them directly and only the end credits reveal them to be interchangeable.) Still, the film finds them at a moment of restlessness when a search for the father leads the two men, along with the mother and an old army buddy (Thi Nag Nguyen) from north to south, to try to get a definitive answer and in the process, outlines an entire country that remains unsettled by a history that remains elusive and frustratingly mysterious.

“Viet and Nam” is something you also can’t quite put your finger on, but only in the best ways as Quý boldly drops a title card halfway through the film and plays with form elsewhere to stir emotion so strongly, from drawing intensity in the sounds of natural environments to a tactility from the 16mm film stock it’s shot on, and after becoming one of the major discoveries at last year’s Cannes Film Festival where it stood out in the Un Certain Regard section, it is now arriving in the U.S. Shortly before Quý kicks off the film’s theatrical run with appearances at the IFC Center this weekend in New York, the writer/director graciously took some time to talk about his process with us, building upon his previous documentaries with his first official narrative drama, and holding on to the feeling he has when he starts a film to see it through.

From the outside, we could say that this film is my first real fiction. [laughs] But for me, it’s already a bit strange to say that because the festivals or the industry likes to categorize everything, so there is documentary and fiction. But as a filmmaker, they are not two different things. The end purpose is to express something, and obviously, there are restraints when it comes to making a fiction or documentary, but at the same time, those are what make them interesting. This film is still a natural progression from my previous films because for me to decide to make a film, it has to come from a certain impulse from inside. I would find it very hard to make a film that’s not really attached to my feeling and, and life experience at that given period and this film is like that.

At the end of 2019, I started to write the film when I was not in Vietnam and the real distance of not being in Vietnam to write a film about Vietnam was very interesting. The question that I asked in my previous film was what is home? In this film, it’s not really clear, but what’s concrete is the history, which is the war, so the question of what is home is asked in relation to this history.

I could see the through line very clearly. In fact, you have a veteran of the war give testimony of his experience late in the film in such a direct way that it reminded me of your earlier short “How Green the Calabash Garden Was,” in which a former soldier reflects on his experience in Cambodia. Was that actually something you could build on for this film?

Yeah, in [“Viet and Nam”], this veteran character has two testimonies. One is the story about a frog during the dinner scene and how he couldn’t eat frog for more than 25 years because of what he saw during the war. That testimony came from the real veteran in my short film “How Green Was the Calabash Garden,” and in a way I stole the real life story [from myself] and brought it to this film. And then the second story of this character is towards the end, this kind of confession that he’s wanted to tell to the wife of his friend for so long, but couldn’t until this moment. This story was different in the script, but because the actor who played the veteran was a real soldier, he told us different stories and amongst them, I felt this story was moving, but I was also shocked and I adapted it to the confession, so it is different from the script based on his real life memories.

In a broad sense, when you were casting nonprofessionals, how much of their experience did you want them to bring into the film? Did ideas change about the characters you initially had in mind?

I think we cannot detach from the idea and the idea of a character and then the reality of a person who’s supposed to play that character brings to us. There is a space between the idea of a character and the person and they don’t need to touch each other, but at best they don’t conflict and I constantly look back and forth between the idea of the character and that real person in front of me to see if they are conflicting each other or actually they support each other. And this film is about memories about the wars, so, for example, during the casting, I met many veterans. Being a veteran means that you have a lot of memories and I asked them about their stories and the process of adapting already started from there. Even though those veterans end up not being in the film, I think they all contributed to the building of this veteran character that we see in the film.

One of the great aspects of the film in general is this idea of elements that resemble one another, but have some separation between them from the past and present to these two main characters that are seen as interchangeable to a certain degree. The latter idea is really bold, but completely in line with the rest of the film, so was it obvious from the start?

Yeah, that was the very first idea in the beginning, how to make them look like one, like one body, one family, one story, one history, one memory. I think this idea is also emotional, it’s not overly conceptual because I think in love we become the other and the other become us, so we look the same, we dress the same clothes, we start to speak like each other and then we start to think like each other.

The film is like a road movie. There is one location that was very clear at the beginning — the war museum because I went to visit back in 2017. It’s on the border of Vietnam and Cambodia, and that part of the history was not known so much in Vietnam even because it was far away. I was quite shocked when I first visited that museum and I kept that memory in my mind. Even the framing of the scene [in the film] when they were walking around the museum, we could see in the background, there are some families talking and that’s from the real recollection. It’s not the same family from when I was there, but I saw a family with a young daughter and I wanted to recreate that scene that I saw.

The most difficult location to find was the coal mine. All of them are in the north of Vietnam, so I didn’t know the area, but I read a lot of newspapers about different coal mining companies and I could see pictures. Of course, filmmaking is always about ideas, but also about practicality and I couldn’t shoot in two different locations so far apart. So I went to the coal mine that you see in the film, precisely because they are the only one in Vietnam still has the elevator and it was impressive. Then I started to find different locations like the house of the characters, the river and so on around that coal mine so that we can keep the budget. But the underground coal mine was a set we built in a cave because we couldn’t shoot in the real coal mine because it’d be too dangerous. Then we had different locations in the south and there are some scenes in my hometown. I like to incorporate what I knew, you know, before into filmmaking because it’s security. You know what you can have.

A lot of the places are given an even greater sensory feel by the use of sound, which I hope not to demystify too much, but is it something you start thinking about early on before you even capture the images?

For the underground coal mine, the sound was conceived very clearly in the beginning. I was thinking about creating a real feeling of an underground coal mine, [which is] dark, but we can hear a lot of activities. We can hear the machine, we can hear the explosion. But what we see is very limited by the frame. And I like when the sound is giving us much more than what we see. I also think I was lucky that we didn’t have so much money [for the budget], so that I was not spoiled. It’s not interesting when you see what you hear in the frame. So by doing this, it created a lot of imagination about the space for the audience while keeping the visual uniform. Also, the sound of the film is quite realistic, but at times it’s very abstract.

From what I understand, the structure of this changed dramatically once you were well into the edit. How did it ultimately fall into place?

I like editing and I edited my previous film myself, but for “Viet and Nam,” I worked with another editor and it was quite an interesting experience. What I like to do in editing is [look into] all of the possibilities for the connection or disconnection of the image and the sound until the point [I think] that, “Okay, this is the film.” That’s a process of trying [out a lot of things] and then realizing that it’s bad and of course, we deleted a lot of scenes and when we delete these scene, it created a hole. So we had to start from the beginning and the two-part structure came towards the end of the editing. Because at the beginning, I wanted the title [card for the film] to be at the end, but [I thought] we need to create a break so that the film can move on to a new chapter and what’s so interesting about a cut to black [for a title card] is that at the same time, it creates a cut and then after that, you can go somewhere else, so it gives you a transition. This time we had to use that so that the second half of the film wouldn’t come so abruptly because when people see the title in the middle, then they know “Okay, now we start to see something else,” a beautiful landscape, so it helped.

I think now I’ve learned to be fair with myself and the film and also the emotion and the reception of the audience. One year has passed and at the beginning, it was a stormy emotion for this, from myself towards my own film and also the film itself didn’t have the easy starting point because it’s set in Vietnam and then the reception in Vietnam was a mess. [Ed. note: The film was prohibited from being screened locally due to what local authorities saw as a negative depiction of the country.] Of course, I had nothing to do with that, but I knew how the film was talked about. And I knew it was not [generally going to be] a [commercial] film in the sense that when you read the synopsis, an audience could expect it’s a love story, but then when they see the film, it’s totally different from what they expect, so maybe it’s not easy for them. But that’s what exactly I wanted to do. I didn’t want to make a traditional gay film because for me, it’s so natural that relationship that it’s about something else. It’s about life. It’s about history. And the characters are gay. I think this film is a special one. It’s a challenging one. But yeah, it’s that.

“Viet and Nam” opens on March 28th in New York at IFC Center and in Toronto at the TIFF Lightbox. It opens on March 31st in Silver Springs, Maryland at the AFI Silver Theater and Cultural Center and April 4th in Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal, Chicago at the Gene Siskel Film Center and Film Scene in Iowa City, and April 26th at Cleveland Cinematheque.