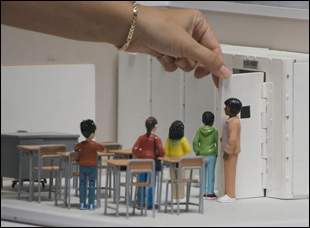

There is something chilling about the opening frames of “Bulletproof,” even though you’re well aware that what you’re seeing is only an active shooter drill, with teachers barricading the doors of the their classrooms as they assess what’s happening in the hallways. After receiving the training that has made their response second nature, the faculty, unemotional and fluid in what would be expected to be a highly charged situation are captured with an equally cold and clinical eye as Todd Chandler and cinematographer Emily Topper observe from a remove that divorces the preparation for such an event from what the imagination would lead one to believe would actually happen, a differential that has created an entirely new business in recent years as mass shootings have become more commonplace.

In fact, the image of staff holding the line against an unseen enemy proves to be a lasting one in “Bulletproof” as Chandler launches a fascinating investigation into the industry that has sprung up to serve the needs of schools allocating more of their already strained resources towards greater protection, visiting trade shows where whiteboards can double as impenetrable shields and security seminars where teachers take target practice. One inventor he meets in Palo Alto actually finds that her kevlar-padded hoodies could take her places that a planned career in the tech industry could not, but what comes across is the greater cost of living in fear when gun violence is seen as a problem that can be solved with money rather than with greater regulation, promoting the sales of even more guns as protection rather than limiting their reach.

Traveling from one part of the U.S. to another, “Bulletproof” highlights how there may be some slight differences in how different regions respond to the potential for school shootings, but draws patterns both from one place to the next as well as throughout time for how certain attitudes have been shaped and ultimately hardened into routine when confronting large systemic issues that go beyond this one specifically and like producer Danielle Varga’s previous work with director Brett Story on the climate change doc “The Hottest August,” the film is able to engage on a potentially overwhelming and abstract threat to humanity by speaking to all the things that make us human – our curiosity, our sense of the absurd and our predilection towards tradition. After a virtual premiere at Hot Docs last summer, “Bulletproof” is finally making its way into theaters beginning with a run at the Metrograph in New York (additionally available on demand anywhere during its run) and Chandler spoke about how he went about such a grand-scale project that could feel specific, creating rules to abide by in the editing room and making a film where audiences would be inclined to lean in.

Yeah, I’ve been teaching off and on since 1999 and the spark for the film was twofold [when] in particular one conversation that happened in the days following a mass shooting that happened in 2015, I overheard a couple of students talking about it and invited the class into a larger discussion. Half of the class had heard about [it] and the other half hadn’t, but it opened up more broadly into this discussion of violence and ideas of safety and security in schools. This is New York City, so part of the conversation was about police in schools and people’s experiences and I remember one student who was not from the U.S. remark that this was such a distinctly American conversation. I just thought that’s astute and [questioned] what about it is so American? That sent me down a path thinking about violence and fear and the culture of security [in the U.S.]

Then I was having a conversation with a friend whose brother was a Navy SEAL and asked what he was up to and he said, now that he’s no longer in the NAVY, he was running these workshops, “How to Survive a School Shooting.” This was 2015 and I just thought, “That exists?” And that led me down a path of thinking “Oh, there’s a film here.” At first, the film in my mind was about the industry that emerged in response to mass shootings. Then it pretty quickly expanded from there as it became clear that it’s an old industry [with] its hands in schools for a long time, mostly schools in cities/schools in communities of color that have been intentionally policed and surveilled for many, many years and then as mass shootings were more widely covered and drawing so much attention, it opened up a whole new market, so that

Expansion of the industry in suburban school systems was interesting.

Then as I started filming, it started expanding beyond industry to really think about this idea of ritual because that idea of ritual or choreography or performance kept emerging. Those were the words I was using to guide all the filming. Whether we were filming a basketball practice or a lockdown drill or teachers being filmed with firearms or math class, they’re all rituals and they all seem very connected and as that student said five years ago, “distinctly American,” so the film became a meditation on that and what kind of questions does that open up?

I’ve heard there were actually two years of filming that didn’t end up in the film. Was there something that clicked into place as you were making this?

When I started filming, I just started and I thought there’s something here, but I’m not quite sure what. And I don’t know that there were two years of full-on filming, but there were about three or four significant shoots. The first place that we filmed was at a factory that makes ballistics-oriented things — body armor, bombproof humvees, things like that, in 2015, and they were making handheld, bulletproof whiteboards, so they invited us in to talk and I still wasn’t sure what [the film] was, but the conversations there were so interesting and the visual nature of this kind of manufacturing seemed really compelling. I also knew that we had to film in schools, and [wondered] what was that going to be like? I used to teach in New York City public high schools, and had some relationships from those days, and got connected with a school called Bank Street School for Children, a private school on the Upper West Side [where] a really incredible teacher invited me into her classroom to film this mock congress where the students play actual senators and congresspeople, trying to get bills passed. So I filmed them debating ideas around arming teachers and safety in schools, and I used that material to cut together not exactly a sample reel, but just a kind of process piece to help me think through what I wanted to do.

I was only able to do all of that because I worked with friends — I called in favors, I shot a bunch of it myself, and a couple of friends who have production companies were really generous, and it allowed me to collect some material and really think it through. Then I used that material to fundraise, and to also then really think more intentionally about both kinds of things that I wanted to film, and the visual language that I was most interested in. In the end we did go back to Bank Street — there’s a lockdown drill in the film, the finished film, that was filmed there, years later, but spending those early days in that school and talking with teachers and students and just observing really helped inform how I wanted to approach this.

Fear is essentially instrumentalized to drive security businesses and there are people who are doing such interesting and more nuanced work around creating schools that take a real holistic approach to nurturing young people and to creating safe environments, but so much of it is driven by money, it was important. [Producer] Danielle Varga and I had this running map of the kinds of things we wanted to be filming. I knew there needed to be a trade show and some kind of startup. And when we were in a place like Texas City, that high school that had been really ramping up their security protocols and infrastructure, there had to be a question of money somewhere in there and we revisit it in the end because it starts with hearing a lot about all the purchases that they’ve made — all the kinds of equipment, the guns, the surveillance systems and when we come back, the person who led that charge is saying, “Well, we had to spend that money that way because that’s what the state dictates,” and he made those choices, but I wanted to at least nod to these larger structural forces that are at work to drive particular kinds of decisions that are sort of quantifiable, where you can buy something and it checks a box whereas a lot of other approaches that are less quantifiable or “solution-based” are harder to support because they’re not as easily bought and sold.

It was interesting to hear that you and your co-editor Shannon actually divided up the different places you went and cut together the sequences on your own, which makes sense practically, but were there interesting juxtapositions when you started bringing the film together?

Shannon was just such a dream to work with, and I work as an editor as well, so I knew that I needed someone else who was going to bring something that I couldn’t to the project. The film is not character-driven. It is organized by location, in that we went to a place and we filmed and that’s a scene, so we sat together and thought about how to structure this and it was important to me that the film spend time in cities and suburbs and rural areas. It’s not comprehensive, but we were in the Northeast, and the West Coast, and the South, and the Midwest, so it wasn’t all in one part of the United States and one of the rules that we came up with early on was that no places could be identified in context — no titles, like now we’re in Missouri. There are a lot of contextual clues, but a lack of specificity was important because I think as soon as you say, oh, well, they’re doing this in Texas, then you can immediately ascribe a kind of causality there, to say, “well, of course they’re doing that in Texas,” or “This is happening here because of X, Y, and Z.” To me, what was more interesting is looking at this as a national phenomenon [where] it doesn’t matter if we’re in Missouri or in Arkansas. We know we’re in a suburb or a city, and those distinctions are pretty clear, but I didn’t want to get too specific regionally.

Another rule we had was that the film isn’t interview-driven by any stretch, but we knew that there were going to be interviews, and we wanted those interviews to be situated in context and it there were interviews with adults, adults were not allowed to pathologize young people, because there were a lot of adults — people who are working in the security field or even educators — who were talking about young people’s experiences, or what it’s like for young people, or what this must be like, and we wanted to really steer clear of that. If any of that were to happen, it would have to be young people speaking for themselves.

I thought about that when we were filming. I liked that kind of slow reveal, and I knew that I wanted the film to make strange all of these things by positioning them together and through contrasts and juxtapositions, set everything just a little bit of askew and maybe a little disorienting. Not to make it hard to watch, but everything’s just a little bit strange, so we thought about that in shooting, really about the kinds of details to pay attention to on the edges of situations instead of going right for the center. Actually, one of the rules was no classic establishing shots, and there’s plenty of shots that establish a situation, but we thought a lot about, “Let’s try to start and end scenes from the middle — no opening, no kind of easing in, we’ll just start, and let’s cut out before it’s done in some way.” Those rules weren’t always adhered to, but I liked those as guiding principles, and [we] thought about how to slightly disorient, but also about withholding catharsis to some degree, which happens in these really small ways.

It was a great pleasure to play with in editing — things as obvious as the teachers you were talking about [dancing to “Happy”], who are being trained in mindfulness techniques. At a certain point at the end of their session, they’re like, “Everyone put your hands in the air,” and it cuts out before they actually get to put their hands in the air, and it doesn’t resolve. There are a couple of moments that that happens, where you think that there’s about to be some gunfire, and we cut out before the gunshots actually happen. For me, the subtext of that, even if it doesn’t translate in any literal way, is thinking about not only withholding catharsis within the film, but that there is no resolution. There’s not a solution and there’s no resolution. Those were guiding principles, aesthetically, to embody that.

“Bulletproof” opens on October 29th in New York at the Metrograph, both theatrically where Chandler will be doing Q & As after screenings on October 29th and November 1st, and on demand, in Chicago at the Facets Cinematheque, in Cleveland at the Cleveland Cinematheque and in Los Angeles through Laemmle Theaters’ virtual cinemas. It is also available virtually through Projectr.