For years, Tiller Russell has been unearthing unbelievable true stories from the criminal underworld, so it actually may raise eyebrows that his latest docuseries “Night Stalker: The Hunt for a Serial Killer” takes on such a high-profile case. Yet for Russell, it was no different when the more people think they know about the Richard Ramirez’s reign of terror in the summer of 1985 in Los Angeles, the more they’re bound to be surprised by what unfolds.

“Everyone had heard the name. Everyone’s heard the title. But no one had authored the definitive telling of it,” said Russell. “I felt I was entrusted with an iconic title for which the definitive telling hadn’t happened, so it’s the same enterprise where it’s driven by character.”

Having grown up around the criminal courts with his father serving the District Attorney’s office in Dallas, Russell once again draws on innate instincts and institutional knowledge to suss out a compelling new investigation into Ramirez’s exploits through the two dogged homicide detectives who were tasked with tracking him down. While Det. Frank Salerno had already achieved public notoriety for helping to bring the two serial killers known as “The Hillside Strangler” to justice, Gil Carrillo, his partner on the “Night Stalker” case, was less well-known, with far less experience to speak of yet a belief that the recent string of murders that had been bedeviling Los Angeles were all the work of one culprit that Salerno wanted to follow up on when few others wanted to.

As it would happen, Carrillo had a personal connection to the murders almost as soon as they started, realizing one of the victims’ roommates was the daughter of a former next door neighbor, and Russell centers him as the beating heart of “Night Stalker: The Hunt for a Serial Killer,” showing the considerable toll it took tracking a remorseless killer whose Avia footwear was one of the only clues that could lead to his arrest. With intense media scrutiny, few leads and a mounting body count, Carrillo and Salerno carried a heavy burden in working towards solving the case and the series vividly recreates the frenzy they navigated with calm in the face of unmitigated evil. Premiering this week on Netflix, Russell spoke about how he went down a rabbit hole as well in revisiting the trail of the serial killer and how he and his creative team found ways to thrust audiences right back into the thick of a particularly sweaty summer in Los Angeles.

I’ve spent my entire professional life sifting and sniffing out crime stories and in some way or another, I keep feeling like it’s all the same movie. Whether it’s “The Seven Five,” “Operation Odessa,” “The Last Narc,” “Night Stalker” or my upcoming feature film “Silk Road,” all of these are about crime in America and mapping the underworld, so this is a story that I have known of for a long time, yet had no personal connection to it until one day my close friend and collaborator Tim Walsh — we were writing for a Dick Wolf TV show [“Chicago Fire”] at the time — came in and said, “I had dinner with the homicide cop who worked the Night Stalker case. I think there’s an amazing documentary in there. You want to go to dinner with him?” And I said, “Absolutely.” Once I met Gil Carrillo and saw how intensely this story had affected him, both as a murder cop and as a man, it really, really gripped me — his willingness to be vulnerable and real and open about how it had affected the course of his life. After I saw that, I thought I had to tell this story.

You bring up something interesting in terms of your career — you’ve never gone to the same place twice and the local culture factors in so much to the stories you tell, has that been a conscious decision to tell stories of crime across the U.S.?

It’s a decision that gets made more unconsciously and gets reckoned with in the material because these stories are a product of the time and place in which they occur. That’s a defining element of them. So you get a story like “The Night Stalker,” that is Los Angeles 1985, this hot, dark, sweaty summer of terror and the place as well as the time are the lens through which the story gets looked at, and very early on, [you recognize] “Oh, this is a character.” There is Ramirez, there are Frank Salerno and Gil Carrillo and there’s the media that is playing cat and mouse with them and the victims and the family members and survivors who lost loved ones who all have their own piece of this and it suddenly becomes a portrait of both the city and the people of the city as well.

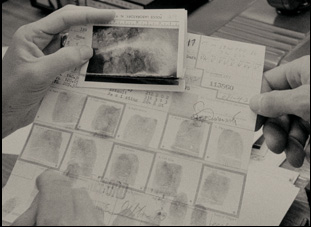

This was one of the great joys and challenges of this project is there was a very specific visual palette that was preexisting. 1985, which is pre-digital, [puts this] squarely in the analog world with a very rich variety of archival materials to draw from. There was all the broadcast news, all the newspaper coverage, and this exhaustive, almost endless amount of crime scene photos, so we wanted to then from all that archival material construct a visual palette which hewed to time and place and made everything of a piece and of a single tone. An example of this is typically everyone uses drones nowadays to shoot their aerials because they’re amazing, beautiful and awesome tools. I use them too, but what we recognized with this was in 1985 Los Angeles to make those shots, you would be shooting in a real helicopter with vintage lenses and the gimbal would be loose so they would have this analog roll and feel to it, so that’s exactly what we did. We rented the helicopter and shot those aerial scenes in a helicopter at night.

This entire story takes place at night, so we wanted it to have that noir feel to it and all of the locations where the interviews are all shot are very carefully selected so they could be as if you walked out of 1985 or the James Elroy version of this. Then even down to the graphics, because we had all these crime scene photos from different angles, what we began to discover and discuss was we thought would it be possible to reconstruct in 3D space graphically what the rooms look like and then be able to move the camera around in certain crime scenes. So that’s what we did, we literally took the geometry of the shots with this amazing graphics company Mint Factory out of France and then the goal was, with this brilliant team of editors – Chris Waldorf and Rogelio [González-Abraldes], who was also an editor on “The Last Narc,” among others – to then find a consistency, a feel to it so that the palette, tone and style was uniform.

In a sense, everything is casting, right? Your choice of who’s telling the story, what story you’re telling is defined by who’s telling it and who you’re telling it with, who your collaborators are – that casting, so in a weird way, each phase of this is if you pick the right people in front of, around and behind the camera, that’s what defines the experience.

My approach in telling these is to make them immersive and 360, where if you don’t hold the gun, kick the door or bury the body or get the cuffs put on you, you’re not in the movie. In this case, it was a conscious decision not to have Ramirez be a centerpiece point of view because this story gave him sort of a bizarre and surreal legacy where he became this kind of sex symbol and celebrity in the circus-like trial and aftermath of the case. It was really important to the filmmaking team not to fall into perpetuating that false narrative or mythos that had enshrouded him. And yes, it’s true, the guy had groupies and this kind of rock star-like afterlife, but we wanted to never celebrate that and steer clear of it. Instead, we wanted to tell the stories of the cops who worked the case, how they did it and what it did to their lives and equally importantly, the perspective of the victims and survivors and what it is that they lived through. They were both dramatically and irrevocably impacted by this, but refused to be defined by it.

There were several. One was the interview with Anastasia Hronas, the woman who was abducted as a child and molested and miraculously released and survived. Sitting there in that room listening to her recount what happened to her [with] vividness and precision [about] what music was playing and those absolutely chilling and heartbreaking details of what happened in that room, I had to look away to keep the tears from running down my face. It was this strange mixture of inspiration or pride or awe at her strength and empowerment and refusal to be defined by that moment. That entire interview was incredible.

Then another one that comes to mind is that at the very end of the series, one of the very last things that I remember having a conversation with Gil about was [asking] him about good and evil and his relationship with God. He ended up talking about [how] each night he goes and prays for the loved ones and people in his life, which we ended up using to end the series, and [when] he finishes his prayers and at the end of them is Richard Ramirez. It took my breath away and stunned me and left me speechless to hear him say it because it was so complex and complicated and nuanced and left me with so many questions and so many thoughts that I felt like “Okay, that’s where we put the pencil down” and it ends.

Have you gotten to show the film to Gil?

He will be seeing it when everybody else will be seeing it, but he was so gracious to entrust his story to us and it was an absolute pleasure and honor to tell his story, so I hope he feels we did him justice. His heart and soul moved me so completely I hope he feels like we made an accurate and loving portrait of him.

“Night Stalker: The Hunt for a Serial Killer” will start streaming on January 13th on Netflix.