Thomas Allen Harris has long been able to see the world in a different way than most. Legally blind in one eye, a condition that makes him see double, he’s had to. Yet it was just over a decade ago while making “That’s My Face,” a Super 8 film about his family’s roots in Brazil that he came to an epiphany that reshaped his vision once more as a photographer and filmmaker.

“That film really talked about the relationship between identities, how identity was not simply the way you were seen by others, but the way in which you see the world because all of us in some way see very differently and as an artist working in the documentary form, it’s really about allowing or opening up the way for people to actually see,” says Allen. “It’s not just what I say, but how I see, and having the relationship between those two spaces.”

This new way of seeing is no doubt what would’ve attracted Harris to Deborah Willis’ eye-opening history of African-American photographers, “Reflections in Black,” even if he hadn’t been asked to appear in the book himself. From daguerreotypes to polaroids, Willis traced the history of African-Americans by contrasting the images created of them versus the ones they created, discovering that in a society where they were marginalized what subjects were willing to reveal about themselves was often as important as the photographers taking the pictures.

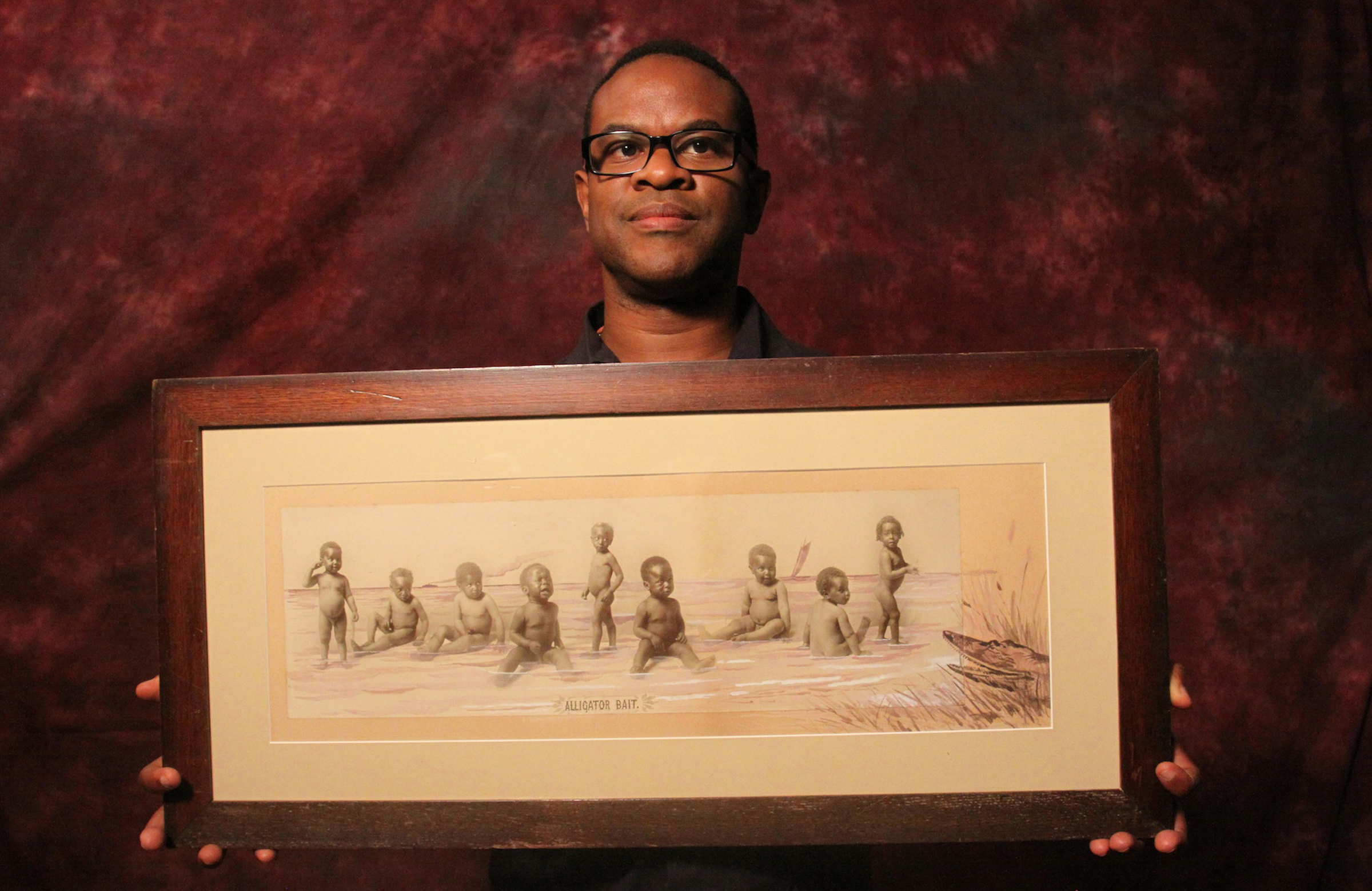

In adapting that book in a deeply personal way to his latest film “Through a Lens Darkly,” Harris invokes his family history once more to highlight how the amateur photography that exists in family albums were a profound rejoinder to the barrage of imagery that portrayed African-Americans as savages through the days of slavery and even beyond, as well as showing how prescient thinkers and community leaders such as Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. DuBois, Booker T. Washington, Sojourner Truth and Marcus Garvey understood the power of photographs quite early and used them to reshape the view of African-Americans in American life.

As filtered through Harris’ own lens, this cultural chronicle is both poetic and insightful, enlivening an entire hidden history as well as preserving it for all to see, which as the filmmaker learned firsthand during the 10-year making of the project has become increasingly important as images have transitioned from tangible artifacts to digital ephemera. Before the film makes its way around the country beginning this week with a release in New York, Harris took the time to talk about tackling such a massive project, which now includes a transmedia component 1World1Family.me, and how “Through a Lens Darkly” didn’t start out as a personal film but inevitably became one.

It was something that I started initially when Deb Willis approached me about doing a film interpretation of her book, “Reflections in Black.” I’ve known Deb since I started working as an artist, but I struggled with this intense encyclopedic book on the history of African-American photography and it occurred to me I really need to actually transform the project into something that really talked about the struggle over representation and have the base of it be the American family album, with an eye towards the African-American representation both in terms of how African-Americans were represented and the African-American photographers and imagemakers and people who were working with the images and imagery from the beginning of photography. Photography started twenty years before African- Americans were considered fully human in this country, particularly the ones who were enslaved.

Was it always your way into this history to include your personal story?

Since I’ve done this three times in the feature-length format before, I’m always aware that I might be in the film, but I did not initially set it up that way when I was shooting. In fact, it was the last thing that really helped bump it into a space where I felt this could go into the world because I tried to really allow other people to lead the narrative. While there was amazing analysis, why would I undertake this as an issue, particularly considering I gave ten years of my life to it, involved a deeper level of writing. The final year [of production] I got some feedback from the Sundance Documentary Fund, which is one of our funders, and also the Ford Foundation, and they really said, “We need you to tell us what’s at risk.”

So I had to put my story in there — secrets, the shame, desires and all that stuff — and I really felt there was a way to emotionally link all these disparate stories that were related. There was also truth in it because I’ve been part of this community for 20 years, studying photography and representation, and my brother’s also an artist on through my grandfather and his interest in history. That’s when it really took off. Maybe even more important than that, it really allowed me to articulate this film from my perspective as a poet, but also trusting the power of the image, [enabling me] to pull back on some of the words and scholar’s analysis and allow the image to be both the critique and the invitation.

You can tell from the visual scheme of how you’ll often have one image fade into another that there is a poet’s hand at work. How did that style come about?

I worked really hard at that from the very beginning. When I thought about interviewing all these different people, I was very interested in creating a black, white and grey backdrop like the backdrop they had in the studio when I was working as a photographer. I wanted to actually have this very particular visual landscape, and it was just as important as the narrative to me. The film always had this very interesting visual grammar, but it really took it to the next level in terms of picking and using the images poetically as opposed to just illustrate the point. The image actually was leading us.

I came across a body of images that Frederick Douglass had generated of himself and [I was struck by] how beautiful this man was and how distinguished, but also how intensely he crafted this visual persona. I could actually track him from the time he became a free person and then started getting his picture taken. He also wrote about [the pictures] and just looking at those images and seeing the way which he faced the camera, having been aware of it, and how he talked about how important it was to take a certain authorship regardless of who was behind the camera, it was really intense.

Those images are like performance art, [with Douglass] knowing that these things would go out and do their work and how it represents the race, particularly during a time when most of the people were exploiting themselves.

Then some of these other images that were taken before the end of slavery, of free people who were part of the community that included Frederick Douglas, were amazing. There’s one image of two men who just look so dapper — they’re dandies, as a bit of a dandy myself, [it was incredible] to realize I have this lineage that was also a political act in terms of self-presentation and using the body as a canvas to perform one’s identity and to affirm one’s humanity.

You’re an imagemaker as well and seeing how the meaning of some of these images has changed over time and how important they’ve become to preserve, has that made you reconsider what you do?

It really helped me to just be very much even more aware of the archives that I’m creating and the importance to preserve that. Over the ten years, we collected over 20,000 images. Many of them have never been seen in film before by all these different photographers, really highlighting African- American photographers who basically have been forgotten. Everyone can say, “Oh, Gordon Parks,” and point to him, but there are hundreds if not thousands of African-American photographers who are part of black communities taking pictures of African American families. A lot of these images also came from multi-racial communities, especially before the 1920s when the Ku Klux Klan went and segregated a lot of the communities out West. We just assume that segregation was the law of the land from the very beginning, but you have these photographers proving it wasn’t so. So all these different truths and realities that I’m seeing in these images are amazing and it just makes me think about how I construct the past in my head and having responsibility in terms of showing the diversity of who were are in terms of our community moving forward.

This film is actually part of a transmedia project that we have been working on called the Digital Diaspora Family Reunion Room Show, and we’ve been traveling to all these different communities [where we ask] people to share their family photographs with us and we help to create narrative out of them and then blow them up to set them aside and have them stand in front of the image. If somebody’s at the edge of the image, it tells the story of the image to our community of people. We now have a fair number of images doing this road show for the last five or six years and it’s not simply my archives that I’m interested in, but our collective archive, especially as we’re at this place now where the family album has totally morphed into something, who knows if it’s going to be Facebook or something that has yet to come into existence.

That’s an interesting point because when you started this film 10 years ago, a lot of the technology which people use to transmit images on was different and the term transmedia wasn’t yet popularized. Did you feel your job changed as the shepherd of this project?

It’s still in progress. I’m not sure where it’s going to take me. As the film travels across the country, we’re doing Digital Diaspora road show and we’re actually starting to get some major support behind the Digital Diaspora road show and I know that I want to turn it into a TV show at some point , whether that’s on the web TV or live TV. Part of my mission has been to create a movement where people begin to think about the way in which they are archiving their family pictures, making them more than something that’s in a shoebox under the bed or this private thing that’s on a telephone or just a blip on Facebook because there’s something potent in there.

These images were taken with this feeling, the potency of love that comes through on the images that we’ve taken of family members of a boyfriend or girlfriend or spouse or a child or a grandparent or someone that strikes you as beautiful. There’s power in there. I feel like there’s so much in this culture that tells us that we’re different from one another and to fear and distrust that difference, but there’s so little that talks about the power of expressing the things that we share in common. When one looks at what we’ve done with this road show, it’s transformative in that strangers can become like family in the best sense of that word, able to see oneself in another or in a landscape photograph. In the midst of this digital culture, which can be very atomizing, it’s so important to see the connectedness in a one-to-one way.

“Through a Lens Darkly” opens on August 27th in New York at Film Forum before expanding to other theatres throughout the country. A full list of theaters and dates is here.