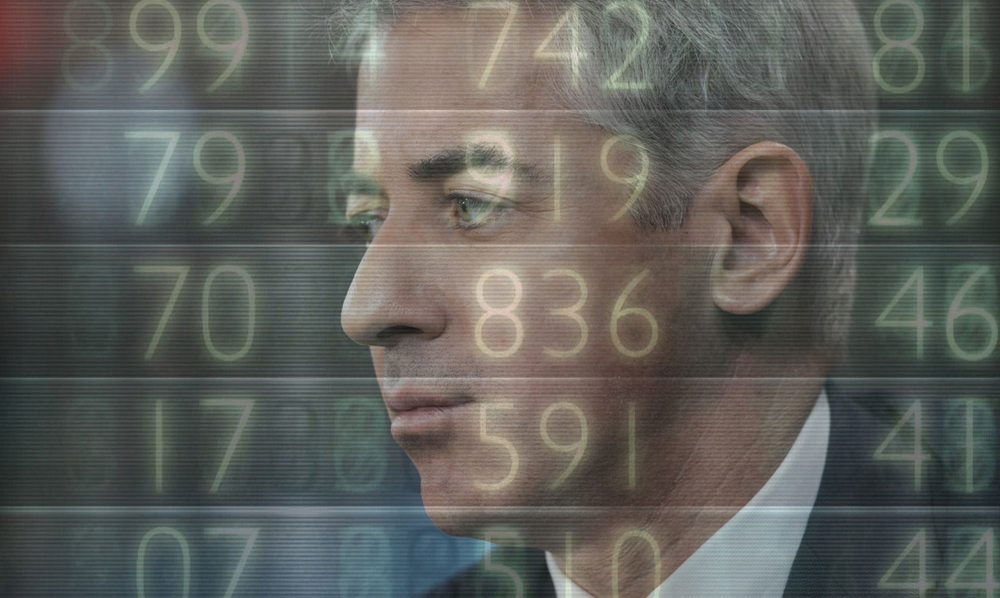

On July 22, 2014, Ted Braun followed Pershing Square Capital Management CEO Bill Ackman into a short presentation on his latest business plan, not knowing exactly what to expect. He was well aware that Ackman was about to bring the hammer down on Herbalife, the billion-dollar supplement company that he believed to be a ponzi scheme through their franchising-dependent revenue stream, selling people more on become distributors of their products rather than the products themselves. However, what Braun did not know was that his movie was being made for him that day, or at least the structure of it, since after it was over, there was no shortage of suspense, instead, just a short of Herbalife, attempting to bring the company down on the stock market after putting nearly $50 million in research over three years to reveal the emperor had no clothes.

Braun’s lean, mean “Betting on Zero” interweaves that fateful day into an stirring study of Ackman, whose potentially quixotic quest to expose Herbalife’s exploitation of lower-income Americans enticed by the prospect of easy money, particularly from the Hispanic community, begs the question if business can be a way of achieving social justice as well as if someone who profits off taking down a bad actor is any better than who they destroy. In addition to the self-described “appropriately skeptical” hedge fund manager, Braun heads to Ponca City, Oklahoma and Chicago, Illinois to find aggrieved Herbalife club owners and a burgeoning movement to get Herbalife to pay back on their false promises of wealth.

“Betting on Zero” is nearly as scrupulous — and ruthless — as Ackman is in his preparations for war with Herbalife, shuffling through the company’s relatively short history in entertaining fashion while bringing out the very human cost of their actions. Shortly after the film premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival, Braun spoke about how he got interested in the subject, building the film out from a single event, and how he went about creating the film’s energetic pace.

How did you get interested in this subject?

I was initially drawn to the subject through a desire to collaborate. Glen Zipper, the producer of the film, and I got to know each other when he was bringing “Undefeated,” which went on to win the Academy Award, out. We became friends and wanted to work together. He approached me three years ago saying he thought he could get financing together for a film set in the world of American corporate conflict. He had a bunch of different ideas, amongst them were two or three sentences about this battle between Herbalife and Bill Ackman. I had never heard of either, but the nature of that conflict and the stakes of it on millions of people in the United States and around the world seemed to have the makings of a good feature documentary.

You build the film around a single presentation Bill Ackman gives condemning Herbalife’s nutrition clubs as a pyramid scheme. How did that structure come about?

That was something we worked on and thought about a lot, but [putting the event there] was a happy accident, a discovery that we made in the process of making the film. I had set out to make a present tense, vérité film about a battle as it unfolded. At a certain point, when it became clear to me that the people at Herbalife were not likely to participate in the film, I was forced to rethink my approach to the film. We had [already] filmed that day with Bill’s wife, and it seemed that I could frame the story as a whole and move back and forth in time from that day. So much was at stake and he had put so much on the line with this nutrition club presentation that I felt the audience would be held by that, and it was a good structuring device. From that, I was able to pivot into another investigative storyline and follow how he came to start the company and different aspects of it.

Did the stories in Oklahoma and Chicago emerge from that or were you tracking a bunch of different stories from the start?

From the beginning, I was looking and following as many different strands of this as I possibly could. My hope was to follow [the stories] as they unfolded. When I decided to frame the story around that day in Bill’s life, I had the opportunity to include some stories that had happened in the past. I had been following [Chicago Chicano community activist] Julie [Contreras]’ group and I had gotten to know Julio [Ulloa, who started a Herbalife club in Chicago] a bit. When I knew I had the chance to move into the past tense, I sat down and talked with him. I felt that his story was moving, and that he was a kind of person and subject that audiences could understand and connect with. He was articulate. He was open. Those are very important qualities in a documentary subject.

Zac [Kirby, who started an Herbalife club in Oklahoma], I had been in touch with early on and had initially decided, because he was out of Herbalife [at that point], that he wouldn’t really fit within my design of the film. When we shifted, I went back to him. He had been reluctant to get involved — he had started his new business, and put Herbalife behind him. But as it happens, he was in Los Angeles for a [work-related] convention, and we met face to face. We’d only talked on the phone before. After that meeting, he said, “Okay. I’ll be in the film. Why don’t you come to Oklahoma? We can work there.” I’d been in contact with both those subjects before the nutrition club presentation, but my decision to include them in the film happened afterwards.

While you don’t speak to anyone at Herbalife — though as it’s noted in the film, not for a lack of trying — you do have an interview with the company’s CEO Michael O. Johnson that you obviously don’t conduct, but appears to be from an original source. How did that come about?

Yeah, that interview was conducted by Giselle Fernandez, who produces a series of interviews with important people in the Los Angeles business community called Big Shots. She’s a veteran and very distinguished journalist and a very prominent member in the Latino community. I think that’s really the only public interview that Michael Johnson has done since the initial appearance he made after the short. I got in touch with Giselle, spoke with her about the film and she agreed to allow us to use the interview, clearing it with Herbalife ahead of time. That’s how we came to use it.

I liked seeing Vanity Fair writer William Cohan in the film too, since he seems to be the one person unaffiliated with either side. Was that important to you?

It was very important. There are a number of people that are very skeptical of short selling and in particular about Ackman’s motives. I, going into the film, shared some of that skepticism and had some of those questions, myself. To be able to invite those into the film through Bill Cohan was a big plus for the film. He was very articulate and provided an important perspective in the film.

Was it difficult to get access to Bill Ackman?

He agreed to participate in the film very promptly. When I first met him, he said he’d be happy to help, but he wanted to talk a little bit more about how we’d work. I went back and had a second meeting with him and some of the members on his team, and we were able to reach a good working understanding about how we’d proceed. He’s a busy guy with a lot of claims on his time, so it wasn’t the sort of thing where it was like, “Come hang around for a week.” We were very fortunate that he allowed us to film him on the occasions that he did. When we did film him, there were no preconditions. I was able to ask him any question, and he fielded anything I put out in front of him. From a documentary filmmaker’s point of view, he was open and candid.

You can tell from the interviews with him, which made me wonder since part of the film’s energy comes from the rapid-fire editing, utilizing snippets of coverage from news channels like CNN or CNBC, are there things you actually may have asked him, but preferred to use a clip from him elsewhere to create a certain texture in the storytelling – to make it more urgent, perhaps?

That was very much a part of the design of the film. Once we decided to move out from a straight vérité, present tense film into something that included the past, we were opening the door to archival material. You’re absolutely right. There are some things that I was able to ask and discuss with Bill through the one-on-one interview that we could also draw from a different source. By using the energy of a TV interview and the sense of scope of the battle that going there provides, we were able to make it a little more engaging and indicate to the audience the magnitude of the tension and stakes that this battle had.

While I don’t want to spoil the film, it’s fair to say this story is far from over. How did you decide to stop filming?

That was a very painful choice for me as filmmaker because I had not intended to finish the film before this conflict resolved. We had scheduled and budgeted it in such a way that we thought we’d be done in about a year, but it became clear that this was going to go on for awhile. Eventually, it became clear that there might not be a resolution within two years of us setting out, so we had to figure out a way to end the film in a way that was satisfying for audiences without a true ending to the story. We arrived at the solution that we did, which I hope is satisfying, a little more than a year ago. It was in March of 2015 that we decided, “Look, we don’t want to be in the same position a year from now. Let’s see what we can do to try and have a film finished by the early part of 2016.” Thankfully, we were able to do it. It stretched our resources to the limit, both our temporal resources and our budget, but we managed it.

“Betting on Zero” opens on March 17th in New York at the Village East Cinemas and in Los Angeles at the Downtown Independent and Laemmle Monica Film Center. A full list of theaters and dates is here.