Shu’aib Raheem was thought to be a man lost to time. When Stefan Forbes started down the road that led to his latest film ”Hold Your Fire,” he had met Dawud Rahman as part of his research into the 1973 robbery of a shoe store in Williamsburg that had gone awry, a crime that Rahman remained in prison for the four decades that followed after it resulted in a 47-hour hostage crisis in which one NYPD officer was killed, though evidence has mounted over the years to suggest it was by friendly fire. Rahman suggested that Forbes talk to Raheem, who joined him on the robbery and later represented him in court, yet Raheem who had been sent to another prison was difficult to find despite once making national headlines, with Forbes coming to believe he had died after seeing the obituary for someone with the same name and a similar criminal record. Still, at Rahman’s insistence, the filmmaker didn’t stop there, eventually finding a lead that suggested he might be working at a nonprofit in Brooklyn doing restorative justice work and when Raheem answered a cold call, Forbes realized he had a story to tell.

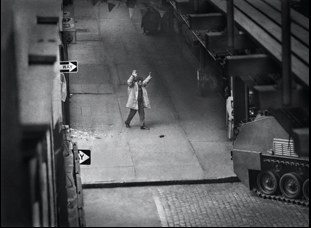

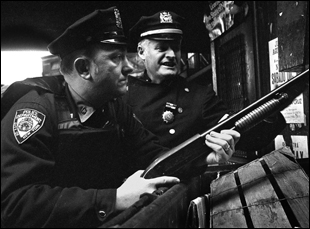

The shock Forbes experienced in that moment might be what audiences feel throughout “Hold Your Fire” where the mere act of talking might come off as a radical concept. It certainly was in the New York Police Department at the time of the Al’s Sporting Goods holdup where officers descended on the store armed with guns, but ended up diffusing the situation with words as the largely untested practice of hostage negotiation pioneered by a low-level cop named Harvey Schlossberg who pursued a Ph.D is psychology before joining the force was put into action by a progressive police commissioner in Patrick Murphy. While there were three hours of trading gunfire that continues to leave a bad taste in the mouths of many that were there, Forbes opens up a conversational space, as Schlossberg once did, where any anger about the situation is presented as only one emotion of many as the complexities of the event, in which preexisting racial and socioeconomic tensions played no small part, and the people involved are given the respect they deserve by simply being given the chance to speak their mind in full.

What once yielded a peaceful resolution to the crisis on the streets once again seems like a revelation when Raheem and Rahman are given the room to share their side of the story for the first time, making it impossible to dismiss their perspective, just as officers such as Al Sheppard and Jack Cambria are less likely to be written off as parroting the company line when the experience that shapes their attitudes come to the fore. After previously making “Boogie Man: The Lee Atwater Story” about the notorious Republican operative who planted the seeds for America’s increasingly polarized political landscape, Forbes ends up making a film tilted towards reconciliation when the subjects themselves may not be any closer now than in 1973 yet seeing them side by side discussing what happened closes the gap of understanding between them. Following the film’s premiere at last year’s Toronto Film Festival, “Hold Your Fire” is rolling out to theaters across the country and Forbes spoke of how he hopes to open up a dialogue in every place it plays, reflecting on how he started talking to people about the robbery that would serve as the inspiration for “Dog Day Afternoon,” and how hip-hop legend Fab Five Freddy came on as a producer on the film and helped give the director a new point of view.

Yeah, all of my films are really about deep cultural conflict, whether it’s race or class in America or a mix of both of those things. I’m always seeking to create a filmic conversation that we’re not able to have in our society, putting different ideas and people who might be enemies in the real world into a cinematic conversation that they’re not able to have, especially in our media where everything’s a sound bite or in our social media where conflict is generated and promoted by AI. I see film almost as a safe space where we can get more granular and transcend these binary oppositions that we almost seem locked into in America.

One of the favorite phrases of cops I learned making this film is “the bad guys.” They always refer to people caught up in the legal system as the bad guys and to many people on the left, the cops are the bad guys, so I think it’s the filmmakers’ job to look behind all those labels. I don’t think these simplistic conversations help us make any progress in society, so a big goal with this film is to let things be complicated and have the messy conversations that our country desperately needs to have any progress on these issues that are tearing us apart as a society.

People have said that in this film they feel Harvey’s radical empathy coming through, and as a filmmaker, I do need to practice deep listening and really give people the chance to speak and feel heard, which is really essential in hostage negotiation and also essential in society among warring elements. But it’s essential to be honest about conflict and put people in opposition and to edit them in a way which makes their conflicts and disagreements really clear because we often try to paper this stuff over with performative allyship or virtue signaling that obscures conflict and never challenges false narratives.

When I finished “Boogie Man,” I thought I really figured out how to edit a complicated film with conflicting viewpoints and I was shocked when I started on this that the event was so complicated and there were so many fundamental disagreements on what really happened that it took me forever to make it work. I’m still not sure exactly how that happened, but I have some amazing editorial consultants and brilliant editors that watched cut after cut and together, we slowly slouched towards Bethlehem. A lot of the ultimate answer had to do with pulling out information and not trying to answer all the questions that everyone kept asking, instead moving the narrative constantly forward, letting these questions go unanswered. It has the narrative effect that one viewer called riding a unicycle on a tightrope while juggling knives. The film feels like it’s constantly about to fall apart and it’s held together by this gossamer thread, but somehow when you get to the end it works. All the unanswered questions hopefully make it richer and give you food for thought, rather than seeking a narrative with finality or closure.

And there’s so many films about societal conflict that feel very kumbaya to me. They’re full of lecturing and honorable sentiments, but they just don’t have a strong story, so when I found out there was this nerve-racking 47-hour siege, it was a no-brainer to structure the film around this actual conflict and hopefully reach a wider audience. We do too much preaching to the converted. I want to make films that anyone would be interested in from any political perspective to reach out and engage different audiences and challenge them with a multiplicity of viewpoints. In America, we pay a lot of lip service to pluralism and I realized while trying to edit this film, it’s really not that easy to construct a coherent dramatic narrative out of competing viewpoints. It almost drove me crazy, especially since I don’t use narrators and it was incredibly hard to navigate these vast cultural rifts between the different people I’m interviewing, but in the end, it was instructive to see how hard it is to tell a story about America taking everyone’s views into account.

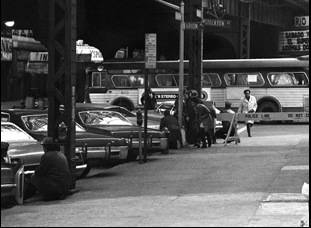

Yeah, I was so lucky to have Fab as a resource because before I started filming, he took me to the neighborhood. We’re just old friends, so I called him and he took me down to the neighborhood in Bed Stuy and said, “This is where we used to buy our sneakers.” I met his uncle who was part of a circle of Black intellectuals back in the day and Max Roach was Fab’s godfather and Fab’s father used to host a Marxist study group, so these guys had thought deeply about all this stuff. It helped me resist the white framing that so much of the media has put on this incident and just approaching it instinctively from different perspectives [because] later when I’m interviewing cops, they’d say, “This wasn’t the Broadway with the big lights and the big stars. This was the Broadway of Brooklyn with the dirty needles and the rats and you had to be on guard at all times.” [Their description] was so cinematic and powerful that I was tempted to use that as an intro into the neighborhood, but I’d already been inoculated as it were by knowing the truth from a different cultural perspective.

Knowing that I had to find the gunmen as well who never had their chance to tell their side of the story in 47 years and were silenced in court. The great civil rights attorney William Kuntsler wanted to represent them, but the judge wouldn’t delay the proceedings three weeks so he could get through Wounded Knee, so their story had been denied so long. It’s your basic due diligence as a filmmaker to want to listen to those guys and the payoff was to be stunned by Shu’aib’s inspiring journey to being a healer and a respected voice in the restorative justice movement. Meeting Shu’aib and Dawud enriched the film so much and Jerry Riccio, the storeowner, as well. He had been represented in the media by the police union, as someone who hated the gunmen and wanted them to be locked up, but I was shocked how much empathy for them Jerry had. I never would’ve found out his real view on the crime from the media.

As doc filmmakers, it’s just crucial that we examine a story from every angle. I was also shocked at the at times radical critique of policing offered by the cops themselves and I’ve heard that it’s upset some brass in the NYPD that these officers are so upset by the way policing is done today, but it’s exciting to practice the deep listening and radical empathy that Harvey Schlossberg preached because you never know what people are carrying around inside and what they really want to get off their chest if you give them the space to do that.

“Hold Your Fire” opens on May 20th in New York at IFC Center and in Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal.