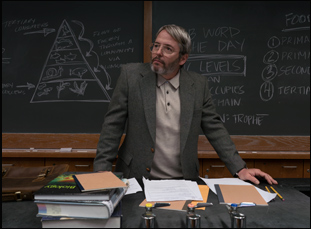

“I think it’s been decided,” a relative of Shmul (Geza Rohrig) tells the grieving widower at the start of “To Dust,” when it’s clear from his face that there’s never been more confusion. His wife Rivka has moved to the great beyond, but her corpse is set to be prepared for consecration according to the tenets of their Orthodox Jewish faith, yet this seems incomprehensible to Shmul despite the decades he’s spent observing a religion that has explanations for such matters. While the rest of his community sits shiva, the father of two young boys heads to the local community college for answers, locating a professor named Albert (Matthew Broderick) with some knowledge in forensic taphonomy, though he holds a great deal more in disappointment, regularly toking up after hours to some Jethro Tull.

While “To Dust” is born out of processing death, writer/director Shawn Snyder fills it with life, not only mining the perfectly mismatched pairing of Shmul and Albert for laughs as the two go about figuring out the particulars of decomposition, but bringing such a zesty spin to a story of recovering from grief, leaving no further explanation needed as to why Rohrig, the “Son of Saul” star grew out a beard for the role that prevented him from being in other films for a year. In fact, everything in “To Dust” appears to be the product of great care and consideration, whether it’s Ariel Marx’s soulful score, the handmade animation of Robert Morgan that illustrates Shmul’s nightmares — his children grow worried he’s been consumed by a Dybbuk – and cinematographer Xavi Giménez’s painterly compositions that always feel as if something’s stirring inside of them even when everything appears so immovable in Shmul’s period of loss.

Remarkably, the film is Snyder’s first, though it brings to bear a wealth of experience he’s accrued elsewhere from a BA in religion from Harvard to his work as a touring singer/songwriter before getting the greenlight for “To Dust.” Spending much of the last year on the road once more following the spirited dramedy’s premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival, the writer/director recently stopped in Los Angeles as the film is being released nationally to talk about the inspiration for the film, how he was able to gather together such a strong creative team and telling a unique story where religion and science go hand-in-hand.

There’s this intersection of so many threads that are woven throughout my life, but the emotional origin was when I lost my mom 10 years ago and dealing with grief in my own way. I come from a reformed Jewish background, which is not Hasidic by any stretch, but there’s a very specific way of grieving in Judaism and I’ve always felt it is incredibly wise and profound and while it’s ancient, it’s amazingly intuitive about what we understand about grief, so in this specific emotional and cultural moment, it was very important to go through the Jewish mourning process as a way to honor my mom. It’s very life-affirming in the face of loss and also understands that this excessive externalized period of mourning is necessary before the timeline continues and you’re pulled back towards life. Given the specific relationship I had with my mom, I came to recognize that any instance of grief is fairly idiosyncratic and so specific concerning the individual that’s lost and the individual that’s left behind and how one needs the honor the person, so even though Judaism offers some comfort, my grief was spilling out [over] the seven days, the 30 days, the 11 months and needed its own expression, so [that became] the emotional underpinning of the film.

The [scientific idea of] decomposition enters the picture in that I never felt comfort at my mom’s grave. I’ve never found her there. I’ve never had peace with those thoughts, [and as a] society and individually, I don’t think we have very healthy relationships with death. We do our best to repress [those thoughts] or poeticize them or gloss over them and the funeral industry profits off the denial of that reality. Nobody wants to talk about it and if you’re having these thoughts, then you’re strange. I wound up grafting those thoughts over the Jewish timeline for grief, so at seven days, [I wondered] what does my mom’s body look like, [then] at 30 days… It took a very long time to realize that if one were to engage those thoughts deeply, it would be a scientific question. and then you would be putting science in conversation with religion and it would make for a very interesting conversation.

Did that lay the foundation for these two characters?

I think your average story of religion and science is that one needs to win and that’s not the way this story was. [laughs] Similarly, I think that often the individual needs to escape or remain [in the religion in] your average Hasidic story in film, and that wasn’t the story we were trying to tell, either. We were approaching all of these [elements] with humility and as you go down the rabbit hole of science and religion and the human experience of grief, ultimately you reach a point where you don’t know. You go through the lengths of science and the infinite minutiae of how a body decays, but then you reach the end and there’s an infinity beyond it of other things to learn. Then you go through religion and you think about the soul and you go to the ends of your knowledge and then when you go through grief, people can say, “Do this, do this, this will make you better.” But nobody knows the idiosyncrasies of a very individual human heart. You reach the end of all those threads and you just have mystery – scientific mystery, religious mystery, human mystery. But when you put those things into conversation – and I think that’s embodied by these characters who from the outset seem like “Oh, this is a man of faith” and “this is a man of religion,” I think you get a lot of gray and as the relationship develops [between the two main characters] and turns into a healing friendship in its own right, that gray gets grayer and as the black and white turns into gray, it’s kind of beautiful.

I know you were able to get the actors in the room together at least a little before shooting – how much of the dynamic you may have had in mind beforehand versus what happened when you saw them together?

I know you were able to get the actors in the room together at least a little before shooting – how much of the dynamic you may have had in mind beforehand versus what happened when you saw them together?

It was always darkly comic. The vision for the characters was always odd couple [where it’d be] this Abbott and Costello kind of dynamic potentially, [where] the two of them just by virtue of their culture clash and the different worlds [they come from] would end up stumbling into those routines, talking about pigs and science and malapropisms and misunderstanding each other. But it would always have one leg in reality, even as the film sort of goes into flights of absurdity. Geza Rohrig came on very early and we wound up having a year-and-a-half of getting to know each other deeply and on a spiritual level. [In real life] he is a very serious man with a lightness to him as well, but devoutly religious — modern Orthodox — so [we had] conversations about the character and how we handle the the blasphemy of the character with respect to the faith and also respect for his emotional process and never be exploitative with it.

So we knew that we needed to pair him with an odd coupling and you write this script and put it out into the world and it finds its champions. I never imagined that somebody like Matthew Broderick would ever come onto it, but we had these champion producers — Emily Mortimer, Alessandro Nivola, and Ron Perlman — who came on and [had] the keys to the candy store. When we thought about Matthew, it was just like an epiphany because there’s a line connecting his body of work to this film and yet it casts him in a what I believe is a new light. Matthew and I [first] connected alone and then with my writer Jason Begue and Geza, we talked through the script a lot. As actors, [Geza and Matthew are] an innate odd couple, and because these are two men who are so different meeting, and we had a very limited budget and schedule, it was Matthew who was one of the biggest encouragers of “It’s a leap of faith, you jump into it and figure it out.” So it was like let’s set the trap, let’s put these two people in context and see the sparks fly between them. The specific nature of how it plays and the comedy came from the juxtaposition of their styles and their approaches of putting it together, but my favorite thing about their performances is that from the outset, you would think that Matthew is here to be the comic relief and Geza’s here to be the straight man, but it was such a privilege to watch the ways Geza makes me laugh and the way Matthew breaks my heart. So it was always deliberate, but this lovely evolving dynamic thing as film often is that delivered way beyond anything I could’ve hoped for.

This is a wonky question, but I loved how you set the mood with the color – how much was that something you could’ve done on set with lighting and lenses versus what you may have been able to do in post?

This is a wonky question, but I loved how you set the mood with the color – how much was that something you could’ve done on set with lighting and lenses versus what you may have been able to do in post?

Again, this was my first feature, so I was the least experienced person on set and it was such a privilege and an honor [to work with] our cinematographer Xavi Gimenez, whose work I always adored. One of the most beautiful things about our film is how collaborative it is and In a strange twist of synchronicity, I had revisited “The Machinist” in putting together a look book of palette images which he shot a week before Emily [Mortimer] said “I just reconnected with Xavi” [because he] shot this other Brad Anderson film “Transsiberian” that she was in. All of a sudden, this incredible DP from Barcelona decides to come over to be in the trenches with us. We talked about it, we got to know each other’s soul and we explored the aesthetics, but we were also confronted with the limitations on set. You approach these things with, “Here’s my Spielbergian shotlist. We’re going to do this huge set-piece and there’s 50 shots on my storyboard,” and then you get there and you’re like, “Oh but I have two hours to shoot it.” So you’re really making these decisions of what is important here.

So much of the visual imagery of the film and how restrained it is an ode to Xavi’s mastery, not only to the craft in a wonky way, as you said, but a mastery of how to yield emotion through the craft. We wanted [the film’s colors] to be grounded in realism, but to have these hints of horror or German expressionism, so [we were thinking about] where the shadows lie and the darkness and how it’s tethered to this B-horror past and how the nighttime would feel very different from the daytime, almost as if you were entering this other genre, and how would we make those woods, which are real woods feel simultaneously real, but a little heightened. But it’s always evolving with our limited time and resources and so much of it happened through Xavi’s brilliance on set and I had so much support all around me [in general]. Ultimately, what’s important is the story, the script, the emotions, these actors and if you know that it’s being captured even in three shots instead of 15 shots by someone as masterful as Xavi, you just trust that. At the end, the economy was born of limitations, but also gut instinct for all of us and I think the economy counters the surrealism and even keeps the absurd places that the film goes to grounded.

Thinking of the surrealism, the animated sequences that depict the Dybbuk and decomposition are quite striking. How did you find the right person to create the animation?

More than anything I love to throw a spotlight on these rock stars [who worked on the film with me] – and there are more nightmares that will hopefully end up on deleted scenes on a DVD or a Blu-ray because they didn’t end up in the movie, but the animator is Robert Morgan and I encourage everybody to look at his work. In the script, I wrote this [scene where a] toe peels and turns into a flower that was digging into this childhood love of Tim Burton and stop-motion. I searched the internet and thereby the globe in a way for someone who was a master of the artform and had a kindred aesthetic and I found Robert Morgan’s work. It’s morbid and macabre, but yet melancholy and emotional and he does this crazy stuff like casts real human body parts with silicon, but also with corpse wax, which is also used by morticians, so his approach is lifelike, but not [exactly]. He lives outside of London and to this day, we have never met in person, but I sent him the script and said, “I would love for you to do this,” and we got the opportunity to know each other as artists and collaborated for a year over Skype.

The first time that we met, I knew this was the guy. He talked about his philosophy about stop-motion and why it lends itself to horror so easily, whether or not you’re doing casts of real body parts or even just animated figures [because he said] it’s like the uncanny valley. [When] everybody’s buying into this is an inanimate object that is being animated, there’s something haunting about that, so when you take a real human life cast and reanimate it, it’s exactly what those nightmares are. You’re infusing life into something inanimate and dead and I thought it was a beautiful way of thinking about the artform. He just got it and it was his wife’s toe [that was the model for the film] and he said of all the work that he’s done, it was the hardest thing he ever had to execute because he had to figure out how the flower would exist inside the toe [before blooming]. It was a number of mechanisms to get a toe to peel open and turn into a flower.

What’s it been like putting this out into the world?

What’s it been like putting this out into the world?

It’s been such a joy and a gift. This is an odd, personal film and so dark and strange that it is is utterly surreal that it found these champions in these producers and found its place at Tribeca and that it found Good Deed as a distributor. It’s been such a privilege to watch the movie with audiences and to get to talk after, especially on the festival circuit, because it winds up being a space for almost group grief therapy. Obviously, I always get asked about the personal roots of the film and it opens the door for folks to talk about [their own personal grief] and how there’s a universal experience and an intensely idiosyncratic individual experience. There’s been a lot of instances like this, one specifically at Tribeca [where] a woman who was a Southern Baptist was up from Louisiana and she raised her hand and said, “I just came up here for the weekend with my son. I don’t know anything about the Hasidic culture. I just saw Matthew Broderick’s name, so we showed up, but I lost my mom three years ago and this movie in ways you can’t even recognize or realize feels like it was written about me mourning my mom.” And that’s why you make art – the empathy machine to let us all feel a little less alone in our strange heads and our strange heart. [laughs] I feel like I see film and art as a conversation in itself. It’s a conversation with a theme, it’s a conversation with the medium and then ultimately, at the end of the day, it’s a conversation with the audience and hopefully it sends people off to have conversations amongst themselves.

“To Dust” is now open in limited release. A full schedule of theaters and dates is here.