It’s the morning after the special runoff election in Georgia when I was scheduled to speak to Sam Pollard and as returns were looking good that Democrats would even up the Senate and just before news would break that a collection of insurrectionists had breached the U.S. Capitol at the urging of the White House’s current occupant, the director, as diligent a student of history as they come, couldn’t comprehend what was unfolding.

“In some ways, it’s both exhilarating and it makes me a little angry to think that here I am on the other side of my life and career and I’m looking at the craziness of the world and it just confounds me,” says Pollard, who has untangled many of the most complex narratives that America has had to offer as a director of such films as “ACORN and the Firestorm” and “Two Trains Runnin’,” a producer on the landmark civil rights movement series “Eyes on the Prize” and an editor on “Gerrymandering” and “By the People: The Election of Barack Obama.” (A retrospective of his work can be seen at the Film at Lincoln Center’s virtual cinema starting today.)

Pity anyone else trying to make sense of this present moment if someone as savvy as Pollard can’t, but just give him time. It would take over 50 years for the filmmaker to have the opportunity to crack open the FBI’s dossier on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. ever so slightly (the full records won’t be fully declassified until the end of the decade), but what he reveals in the electrifying “MLK/FBI” is an astonishing recalibration of what role the federal government played in stymying progress towards a more equitable America during the 1950s and 1960s. Where many Americans saw hope, the Bureau’s records indicate J. Edgar Hoover identified the civil rights movement as a domestic threat to be stopped and ordered surveillance on one of its most prominent leaders in Dr. King, yielding little evidence of posing any danger but the wiretaps and informants relaying information about his extramarital affairs that could be used to damage his public profile.

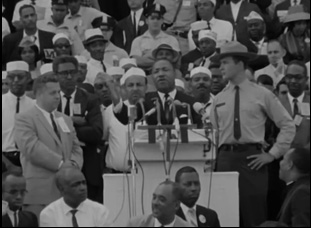

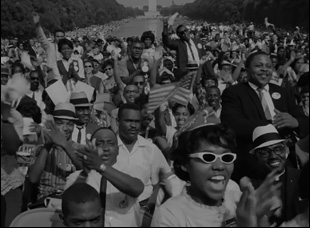

As the FBI’s investigation of Dr. King proves to be more damning of those pursuing it than the pursued, Pollard launches a fascinating inquiry into how the FBI not only recognized attacking Dr. King’s image was their strongest gambit in maintaining the status quo but could hide their more unsavory activities behind the trust they had cultivated in the public’s imagination of the institution through TV shows and movies projecting their strength and sanctity. Though the intricate selection of archival materials put together by Pollard and editor Laura Tomaselli, images that have been consecrated into history take on a new life as you come to understand the mental strain Dr. King experienced when leading a movement under even more intense personal scrutiny than had been known publicly before and the lengths the FBI went to take him down and while “MLK/FBI” is bound to take your breath away in terms of recasting history as you may thought it to be, its craft at showing how it is shaped by those in power is equally stunning.

With the film’s release this week after a celebrated fall festival run at Venice, Toronto and New York, Pollard spoke about building off the work of Dr. Martin Luther King biographer David Garrow, finding complexity in the most innocuous imagery that’s extended to the public and how he’s carried that responsibility in times when notions of truth are particularly fragile.

In 2017, my producer Benjamin Hedin read a book by the historian David Garrow about how King had been surveilled and monitored by the FBI, and he said to me, “I think we found our next film.” We had just finished a film called “Two Trains Runnin’,” so then I read the book and called him back and said, “You’re absolutely right. This is our next film.” I reached out to David Garrow, who I knew from [being] one of our consultants on “Eyes on the Prize,” and we optioned his book and flew out to Pittsburgh where he lived. We sat down with a camera crew and [for] about four hours, we were interviewing him about why he wrote the book and the concept of the book, which became the framework to tell the story about King.

We knew that we didn’t just want to have David Garrow. We wanted to try and find some close confidants of Dr. King from that period and two of the surviving members of that group, Clarence Jones and Andrew Young, [were people] who we wanted to reach out to. We wanted to reach out to Joseph Lowery [too], but he really is very sick. Then we knew we wanted two stories, one to give you the framework about the FBI and [J. Edgar] Hoover — what they were and the mythology of the FBI, and we wanted another story, which was Beverly Gage and Donna Murch to talk about the FBI [counterintelligence] and the lengths they went to infiltrate and monitor organizations like the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Nation of Islam and the Black Panther Party. We [also] wanted to make sure that we had somebody from the FBI talking, so we found Charles Knox, a former FBI agent who lives in Texas, and then we decided to reach out to James Comey. My initial reaction was, I doubt he would say yes to an interview. I was quite surprised that he did agree to do an interview for the film.

This was one of the most powerful uses of audio interviews I can remember when there’s a contradictory nature to what you’re seeing with what you’re hearing. Did that approach immediately come to you for this?

It was initially the way we felt we wanted to make the film. We said to ourselves at the beginning, we didn’t want anybody on camera. We wanted to do all the interviews in voiceover and normally we would’ve just done audio, but some of our funders are concerned about that, so we decided to play it safe by shooting them all on camera. [minor spoilers regarding the ending] Fortunately when it came to the epilogue, our editor Laura Tomaselli had the idea of showing these people on camera at the very end of the film, so it was a great approach to introducing these people we had heard from throughout the film.

Yeah, that was something I originally thought about at the very beginning of the process too. I was very familiar with all these films about the FBI, growing up watching them as a young man, so I sent a list to our editor Laura with “Walk a Crooked Mile,” “Big Jim McCrane,” “The FBI Story” and other films, plus the FBI television series, things we wanted to get clips from to be able to use in the film because there was a mythology growing around the FBI that even I, as a young man, bought into. We really wanted to dig into that mythology and what it meant to be an FBI agent supposedly back then and what the reality was.

Of course, you had David’s book to work off of, but was it like wearing a decoder ring going through all those FBI transcripts and parsing that material when you knew it must’ve been compromised in the way that it is?

Yeah, it was a lot of material to go through, so Ben [Hedin] had really found all this information and had been able to go through and see what we felt was necessary to help tell the story and shape the arc. When you’re making a documentary like this, it involves a lot of detective work on the part of the producer, on the part of me as a director, on the part of the editor and also what the archival producer will do in finding the material. We had a really fantastic archival producer in Bryan Becker, who did a phenomenal job in finding all of the stuff I had seen before, and all the new stuff I had never seen before or heard before.

It was a challenge because I didn’t know how much of it existed, so when we found the stuff with him on “The Merv Griffin Show” talking about his personal life, that was like gold. I was a little reluctant initially to use it because I was like, “Who really cares [about casual chitchat]?” But then Laura made a good point, which is that it’s an aspect you can look at King in a different way. Then when she found that footage of King with his family and his kids, his parents and his family playing in that playroom, that was great too. Then there’s the stills we found of King at his dinner table or with his kids playing baseball and it gives you another sense of Dr. King, not just as the gentleman who was arrested in Birmingham or marching in Selma or in Little Rock.

Really going back to 2006 when I did this documentary about John Ford and John Wayne, it’s been very important to me to look at these people in multidimensional ways. Not just create hagiography of these human beings but to get to know people in all their complexity if you can.

Are there any connections or revelations you make digging through this material that you hadn’t before, even with your great knowledge of this time?

What was revelatory for me was in some ways working on this film took me back to April 4, 1968, two days after my 18th birthday. I’m watching the news at home, six, seven o’clock, and Walter Cronkite came on and he announced that Dr. King had been shot. And I was like, “What?!?!” I couldn’t believe it. Martin Luther King was shot at the Lorraine Motel, and these films have the experience of dredging up to me a past that somehow became a little distant for me, but now becomes front and center again in my brain.

I’m constantly surprised. You would think I’d be cynical enough not to be surprised anymore. But every time something happens in this democracy, I’m surprised. This past weekend, listening to that tape an that conversation between Trump and the gentleman in Georgia [Brad Ratffensperger, the state’s secretary of state] left my heart broken. The idea I have to hear in the news that 12 senators of the Republican Party, are going to stand up to object – object – to the election of Joe Biden, it stumps me. It surprises me that over 100 members in the House of Representatives are going to do the same thing. Sometimes I can’t believe I’m living in a democracy, but maybe that’s what it means to live in a democracy is to live through all this craziness because you know and I know that if we lived in an autocratic society, some of these people would be eliminated.

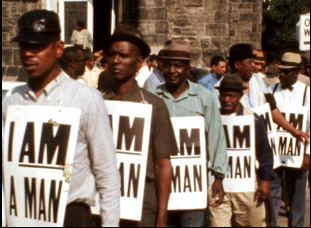

All [making this film] did was made me realize that the stuff that we were dealing with in the ‘60s is so relevant today. It’s like what?!? It’s still going on. The idea that people are talking about in this country today that we have a president in Georgia two days ago talking about the fact that if you vote for a Democrat, they’re going to destroy the suburbs and they’re going to bring socialism — [that’s] the same kind of dialogue we heard in the ‘60s. It’s like the woman in the King film asking Dr. King, “Don’t you feel your protest is causing the riots?” You heard that same stuff about Black Lives Matter this past spring and summer. When is this ever going to change in America? So I’m gobsmacked. I should be more cynical and say this is normal, but still it confuses me.

“MLK/FBI” opens in virtual cinemas on January 15th.