It isn’t every day one of the world’s most famous producer walks into your office and says, “You want to hear a story…and get your camera ready.” But that’s about how it went when Frank Marshall told Ryan Suffern the story that would rival the “Indiana Jones” adventures he’s producing in describing Oscar Ramirez, a Guatemalan man who grew up in Massachusetts after being a rare survivor the Dos Erres Massacre, one of the most devastating mass killings during the brutal reign of General Efraín Ríos Montt in the 1980s. The story had been relayed to Marshall by a friend from high school, Scott Greathead, the human rights lawyer who had taken on Ramirez’s case against one of the commandos responsible for the 229 deaths that occurred in the single raid, and the two were just outside Los Angeles in Riverside, California in federal court so that Ramirez could give testimony.

You can now hear his remarkable journey, as well as the parts he couldn’t possibly have known in his decades away from his homeland, as it’s recounted in “Finding Oscar,” which shows how fortunate Ramirez was to escape, but expands into a fascinating investigation into the 200,000 who disappeared during Guatemala’s 25-year civil war and the ongoing drive by forensic anthropologists, among others, to identify them and restore their names to history. Suffern criss-crossed North and Central America to get the whole story, uncovering uncomfortable geopolitical truths about how such a profound tragedy was allowed to unfold without intervention. Recently, Suffern spoke about how he hit the road almost immediately after hearing of Oscar, getting inventive in telling a story from the past through evoking its locations, and how the film has grown even more relevant since production wrapped.

After you heard this story from Frank Marshall, was there something that specifically intrigued you enough to make a film?

I spent the day doing a little bit of filming with Oscar [immediately after], his attorney Scott Greathead and Fredy Peccerelli, who is the director of the Forensic Anthropology Foundation of Guatemala. It was a remarkable day, to say the least, sitting in this courtroom with Oscar and hearing him read this prepared victim statement. I didn’t really know what to make of it. I felt like I had just inadvertently captured the end to the most fascinating story. That was not without its own intimidation, particularly because I’d never even been to Central America, much less Guatemala. Nor had I really told a story of this magnitude on this subject — talking about a massacre in the midst of a genocide, even though I’ve been involved with a good deal of documentaries that involved human rights issues, whether it’s climate change or LGBT rights. So it was daunting, but at the same time, I told my wife, I said, “I think I’m going have to go to Guatemala to make this because this is just too incredible of a story not to try to film it.”

You’re really able to tell this story though a lot of the places you travel, just giving a sense of them. Did just being in Guatemala leave an impression on you?

This story has been told in previous iterations — there as a great piece of journalism in ProPublica as well as a radio piece on This American Life that proved that it was a compelling story both in print and radio. But I thought what really makes this story compelling is the visual. You hear this story that starts off in the jungles of Guatemala and ends in the suburbs of Boston of all places and when I first got introduced to Oscar in February of 2014, Boston was covered in literally an avalanche of snow. So I was motivated to try and capture Oscar in Boston because I loved that juxtaposition of the snow cover framing him with what I envisioned would be the lush jungles of Guatemala, though I never had been there before.

It just so happened that [Oscar] was going to be in New York a couple weeks after that first day of meeting Oscar and filming with him in Riverside, California, So I asked my cinematographer if he was up for taking a little road trip up to Framingham with really no idea of what we were doing yet, certainly [with] no budget or plan of attack, but just trying to take advantage of being on the East Coast, so a couple weeks after filming the first period with Oscar in Riverside, which proved the be the end of the film, we filmed what turned out to be the opening shots in the film [where] we establish Oscar in Framingham with his family. Without really any intention, we had captured the opening of the film and the end of the film, and it only took us two-and-a-half years to get the rest of the film in between.

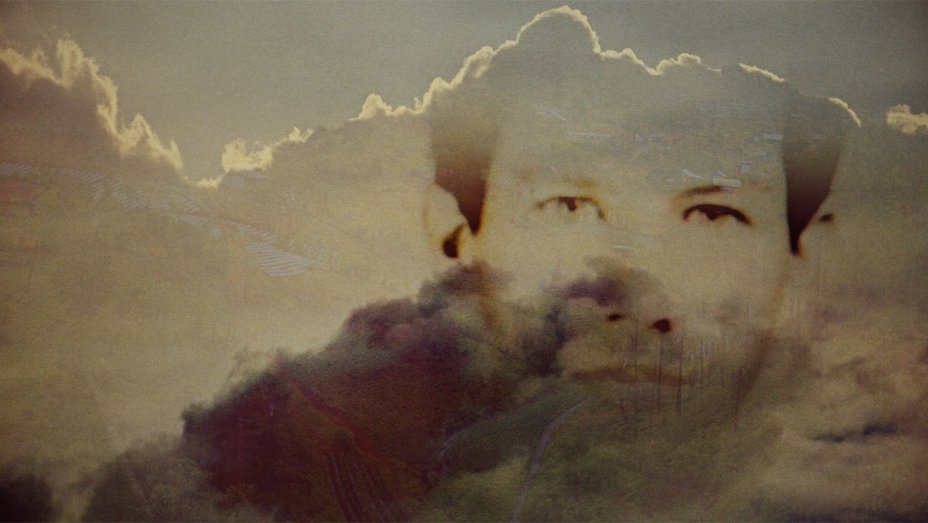

When I first got down [to Guatemala], I was immediately taken with this place. It’s a beautiful place. The landscapes alone with the volcanoes and jungles are incredible. But the people are beautiful, particularly the Mayan culture with the color that just jumps out all over the country. Very early on, my cinematographer and I talked about the idea of really trying to communicate through these beautiful [landscapes] and juxtapose that against the horror of these places that these people have experienced in their all-too-recent history, as well as the idea of invoking the sense of going to Dos Erres and filming where [this tragedy] took place. Many of these shots don’t have any human beings in them and [that was about] trying to invoke the consequences of this massacre of wiping this entire community from the face of the earth because we really didn’t want to recreate these horrific events, and yet we still had the challenge of how to visually communicate the brutality of the massacre.

You mention the ProPublica and This American Life stories, and of course you have Oscar’s perspective on what happened. But given that so much of this history must’ve been hidden, was there much of a foundation to build on as far as telling the story or did you really have to investigate heavily?

We did benefit from the fact that the story had already been published in ProPublica, which is a really in-depth piece of journalism, so there was a framework of how the story had been told previously, though it was somewhat timestamped [since] it had been published in 2012. Many things happened since and there were several people and places that I don’t think they had the ability to go and interview, so a big part of our process was just getting to Guatemala and seeking these first-hand participants out. In the telling of this story, it was always mentioned that because Oscar was two years old, he was too young to remember the massacre, but going there and spending time in Zacapa with the family of the soldier that abducted him and still has a loving relationship with Oscar — he was a member of their family — and hearing some of the stories of when he first showed up with the lieutenant, it really hit home that just because he had no memory of it didn’t mean he didn’t experience it. Having a three-year-old daughter myself [at the time] of making this film just created a wealth of empathy for what Oscar had gone through at such a young age.

Similarly, going to Winnipeg, Canada, and meeting Ramiro, the older boy, I’ve never had a more emotive interview of both the subject and myself. Everybody in the room was literally in tears and just saw how close under the skin this whole experience [was], not just the massacre but really his entire upbringing, knowing all too well that the person who was raising him was involved in this murder of his family. To have that conversation with Ramiro was just heartbreaking, and again, wouldn’t have been afforded had we not made the effort to go speak with him in person.

How did you go about getting archival materials? The footage of Dos Erres before the massacre and your use of contact sheets are particularly striking.

We had an amazing researcher, Alexandra Bowen, at the Kennedy/Marshall Documentary division, who unearthed some amazing footage and stills courtesy of the Ronald Reagan Library in Simi Valley, so that’s where we got that amazing footage of [Reagan], just a couple days before this massacre transpired along with all of the stills and contact sheets. But we also benefited greatly from the fact that there have been several activists and documentarians throughout the decades of this struggle in Guatemala, both in the 36-year-long civil conflict between the Guatemalan government and the guerrillas, but also [during] the Peace Accord [where there’s] still a search for justice.

What was amazing was to reach out to the different activists and documentarians and then have them be so generous to share their footage with us, which really filled a different [area] in the world that we were talking about to actually see first-hand what their estimation of the initial operation looked like or [when] the information when we brought all of the bones and articles of clothing and laid them out for the community [as proof]. That imagery is incredibly powerful, and it really helped in the telling of the story to be able to see what the people were experiencing then.

Was there a turning point for you in what this film could be?

This wasn’t your typical documentary where you’re needing to wait for the story or chasing it in real time. We benefited from that [confidence in knowing] we had shot what was going to be the last scene of the film first, and here is this incredible search for justice, which takes decades starting in Guatemala and ending in Boston, that leads to the discovery of this little boy who’s now a man, a father of four and very much living a version of the American immigrant story. Now, he’s participating in that same justice. You couldn’t ask for a better telling of this story in the search for truth and justice.

It’s also a daunting story to tell because there are so many macro-contextual historical elements to it that sometimes I worried that it would be bogged down with the history of it all for an unassuming audience. So in working with my editor Martin Singer and my co-writer Mark Monroe, we were able to develop a balance to be able to stay within this very intimate, personal story, but figure out a way to bounce out every so often to inform the audience of what was happening on a larger scale, both within Guatemala as well as in the United States and the [larger] international community. Once we were able to get into the edit room and see how bouncing back and forth was effective, that was a turning point for us that we felt we could keep the audience engaged in really what we envisioned being more like a mystery or a detective tale, not wanting to overwhelm the audience with the horror that was the Dos Erres massacre, but also know that, at some point, we were going to tell it first-hand through both the accounts of the victims as well as the perpetrators that we spoke with.

Given those themes of immigration and current U.S. entanglements around the globe, has it been interesting to travel with this film with how relevant it is to this time?

Yeah, we finished this film in late August and we were very grateful to premiere it at the Telluride Film Festival. It’s played about 15 film festivals since and the film hasn’t changed, yet it seems like the world around the film has certainly changed since November 7th and definitely January 20th. There are issues at the core of this story that you can’t not touch upon – be it U.S. foreign policy or immigration or genocide – in the Americas in our lifetime, but these are issues that are all the more timely right now, so we’re certainly hopeful that this particular individual story – the search for this one survivor — helps to start a larger conversation, not just in the past tense, that there is a consequence to the decisions that the U.S. government makes as you see that ripple effect around the world, [in] getting a better idea as to why so many Guatemalans and Central Americans have sought refuge in the U.S., fleeing this very violence that our government has a culpable role in having helped to create in the not-so-distant past as well as getting to put a face on an undocumented Central American here in the United States. We’re hopeful that audiences that are unfamiliar, as I was, with much of what had happened in the ‘70s and ‘80s in Central America and Guatemala specifically, leave the theater with a real desire to engage in that conversation going forward.

“Finding Oscar” is now open in New York and Los Angeles.