Long before Patrice Leconte used the big screen as his canvas to dazzle the eye with such productions as “Girl on the Bridge” and “The Widow of Saint Pierre,” he was more than content to use a pen and paper as his favored artistic outlet. After film school, his stories for the French magazine Pilote were always accompanied by sketches and even before film school, he would bring inanimate objects to life in his earliest shorts using paper cutouts. Decades later, he would become a cutup himself, becoming a king of comedy in his native France with films including “My Best Friend” who has embarked on a new adventure with his first full-fledged animated feature “The Suicide Shop.”

“I’m like a cork floating in the ocean,” Leconte told me about the career detour, a day after the film’s triumphant North American premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. “I’m just getting by with the wave that’s coming my way.”

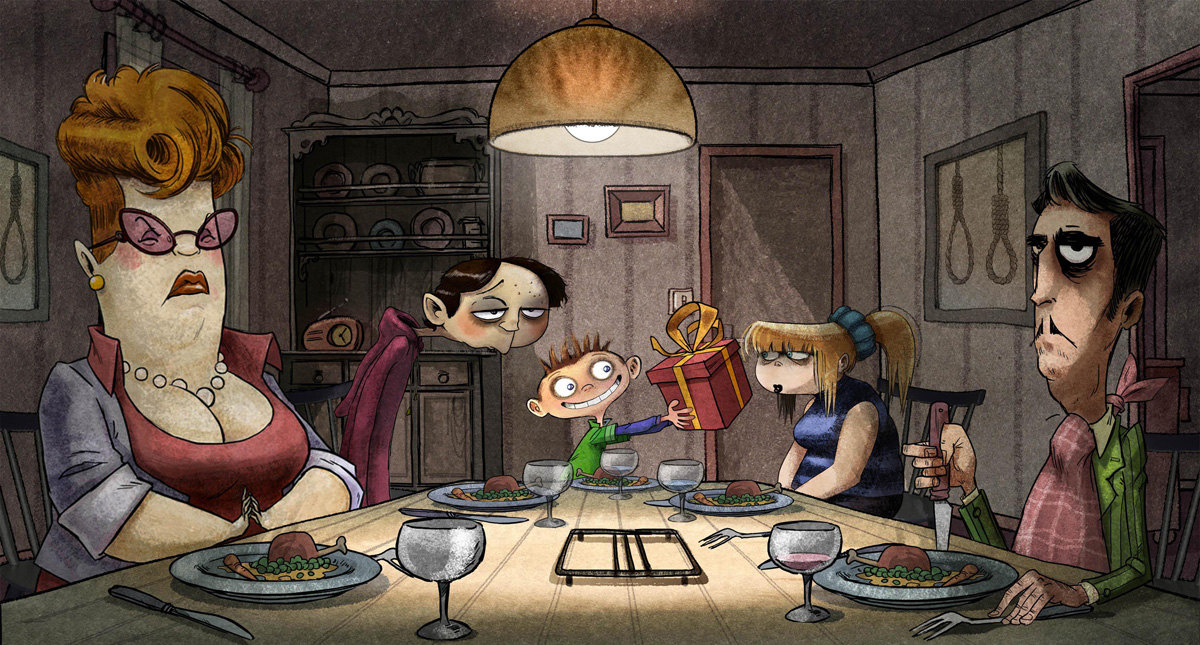

However, Leconte has created his own wave with his adaptation of Jean Teulé’s pitch-black comic novel about the Tuvaches, a family that has discovered their joy in life is to sell all the equipment necessary to depressed customers to preemptively end their own. Toxic mushrooms, razor blades, sleeping pills and even stools to accompany their nooses made of the finest hemp rope, their store is the only place one would want to go before reaching the afterlife and yet Leconte, who insists that a goal of every one of his films is to bring an audience “higher rather than lower,” unearths a heavenly sense of humor from other people’s hell, vibrantly recreating Teulé’s coming-of-age story about the family’s youngest son Alan, whose unabated optimism makes him an outsider until his father Mishima is driven insane by his cheeriness and he is called upon to bring the rest of the family closer together.

Appropriately laced with melodies as sharply honed as the samurai swords the Tuvaches carry for seppuku, the film also boasts an innovative effect for the animation that makes “The Suicide Shop” appear as if it were a pop-up book, with each detailed, individual layer particularly eye-catching in 3D while retaining a distinctly handmade quality. That was essential for Leconte, who loved the process so much he claims he’s already on the lookout for a second animated feature, but in the mean time, he had a few minutes to spare to talk about his first foray into the medium, his favorite visual gag he snuck into the film’s elaborately detailed backgrounds and why despite earlier suggestions to the contrary, retirement isn’t in the cards any time soon for the gracious and endlessly energetic director, who with his wiry frame and feverish gesticulations could be mistaken for a cartoon character himself.

You’ve actually had a long history with cartoons, so did you always have the desire to do a film that was animated?

I always liked drawing and watching animation movies, but even if I went through this phase in my early career, I never had the desire to make animation movies before. A young producer proposed to me to do this film and I really liked the proposition. It was brilliant and extraordinary for me at that time, which proves that producers sometimes have good ideas.

But you passed on this idea as a potential live-action project and came back around when it was proposed as an animated feature. What was it that made you think it would work as an animated musical when it wouldn’t in live action?

Tim Burton could’ve made this movie as a live-action film because he has an incredible talent to offset things and not be in real life. But I don’t have this talent. My films are more realistic/naturalistic. And I was really thinking this particular story as a live-action film would be really, really bad, so that’s why I found the idea really, really brilliant because making an animated movie is taking things and putting them in another universe, which is already not the same as real life. The same thing with the musical [aspect]. It’s been my dream for a long time to make a musical. So for me, it was going in the same direction, offsetting things from reality because in real life, people don’t sing. This was all part of the same unexpected will to do something that was not real life, but was still around real life.

Was it a liberating experience to do animation or was it more restrained given the amount of work that goes into every element?

In the end, after making the movie and going through all the processes, I felt that there was much more freedom in doing this than doing a regular movie in the inspiration process and also the directing process because here you have no limit. You can do whatever you want. There’s no physical camera, so you can put it anywhere you want.

This film uses an effect called 2D Relief, which has never been used before, but gives the film incredible perspective as far as the depth of frame with layers of background, especially when presented in 3D. Was this an innovation you were driving as a filmmaker or did the technology already exist in some form already and you simply were the first to utilize it?

I was really adamant about the fact that this movie had to [appear hand-drawn]. I really wanted the film to feel that the film was [comprised] of drawings. I didn’t want it to be 3D animated by a computer, like CGI because you lose the feeling of the drawings, so as a consequence, the crew and the company I worked with for this project put the method together for this project. I wanted the film to look like those children’s books that you open and suddenly everything is unfolding and coming into 3D. That was the main influence to get the look of the film here. The process was designed for this film and when they showed it at the premiere at the Annecy Film Festival in France, the whole Pixar crew was there and they were like, “Wow, how did you do that?”

Because you’re able to sneak all these little things into every inch of the frame, did you have any particular favorites? I think the skeleton that served as the shop’s door chime might’ve been mine or all the film posters — even in this incredibly depressed town, there’s still movies.

There are a lot of little details that were put everywhere, so people will go and see the film a second time and look for them. Once in the film, there is a marquee on the movie theater and we had to choose a film that was being played in the theater. I made in the ’70s a film that was really famous in France, a very big comedy called “Les Bronzes,” [set at a] in a vacation club in Tunisia, so I used the French title “Les Bronzes” and I made it what we call a verlan in French [an inversion of syllables, like slang] “Les Zombres,” meaning I just [switched] the two letters with exactly the same poster, but very sad. It’s my favorite detail.

What was the most surprising thing about this process for you? And since I had heard talk around the time of “My Best Friend” that you were thinking of slowing down, has this been a rejuvenating experience?

What was surprising was this process taught me patience. Because I knew making an animated movie like this was going to take a long, long time, but I didn’t think it was going to take that long. I’m a very active person, always ahead of the game in trying to do things very quickly and I had to wait three years for this. And regularly when I’m tired, I always ramble about that. Like I’m going to stop making movies, it’s too tiring. So probably at that time [of “My Best Friend”], I already started to say that. I like making movies too much, so I just can’t stop.

“The Suicide Shop” does not yet have U.S. distribution, but opens in France on September 26th. It plays once more at the Toronto Film Festival today at the Scotiabank 2.