This evening when Nicole Perlman presents the premiere of “The Slows” at the New York Film Festival, it may feel as if no time has passed since she graduated from NYU in 2003. She’s still slightly nervous about what her “impossible-to-impress” parents will think, though she suspects “they’ll get a kick out of it,” and after leaving New York for Hollywood thinking she’d be a director, she finally can say so without reservation, making the kind of thought-provoking sci-fi spectacle full of ideas and imagination that first led her to pursue filmmaking in the first place.

This is how, at just under 20 minutes, “The Slows” can feel even bigger than the types of films Perlman is more used to working on as a favorite of Marvel Studios, co-writing scripts for “Guardians of the Galaxy” and the upcoming “Captain Marvel,” and while her directorial debut may involve a fraction of both the time and money that’s usually required of such endeavors, it turns out that Perlman is as adept at realizing entire alternate universes on screen as much as on the page, stepping into a particularly fascinating one through adapting Gail Hareven’s 2009 short story of the same name for The New Yorker. Imagining a world in the not-too-distant future where embryos can be harvested in a lab and brought up to speed as adults in only a matter of days, “The Slows” follows a journalist named Eryn (Annet Mahendru) into a compound in the forest where children are still made the old fashioned way as they face the threat of being eradicated.

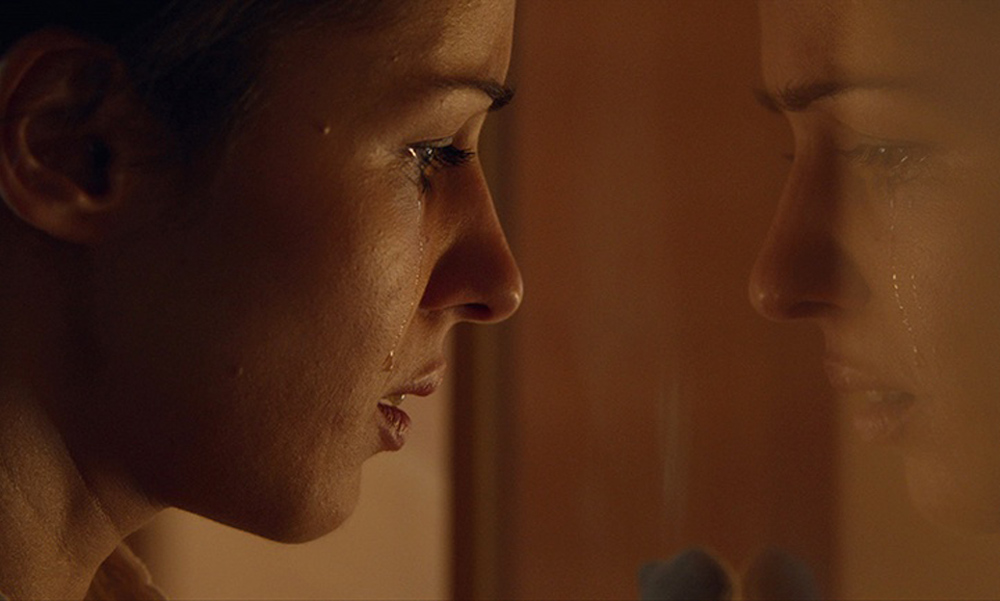

While the cagey work of geneticists can be seen as a way to take the burden off women to reproduce and let kids off the hook in dealing with the whims of puberty, allowing for more attention to be paid to grander human endeavors such as protecting the environment, Eryn’s encounter with the Slows, as they’re known, and in particular the pregnant Greta (Breeda Wool), exposes the gaps in such idealism in the face of reality where personal proclivities and instincts cannot be governed by a one-size-fits-all model. Perlman is able to make this clash of cultural attitudes feel inherently personal, yet never small in scale, whether in its scope of inquiry or the size of the world she’s operating in, contrasting the cold efficiency of the ultra-modern genetic labs Eryn first walks into with the equally chilly yet wildly verdant forest in which the Slows have set up camp, hidden behind a translucent, digitally-enhanced curtain (since even they can’t be completely resistant of contemporary trends).

A provocative film bound to open minds as much as eyes, “The Slows” naturally took a long time to get to the screen and following an exciting premiere at Fantastic Fest in Austin, Perlman spoke of how she found a partner in the New York-based nonprofit film foundation Cinereach to finally get to make it, engaging in an entirely new side of the process in directing and finding her film tribe in Oregon.

I love stories that make you question things that you always assumed to be true, and any story that’s about certainty and having something that cracks that certainty tends to be something I’m really interested in, so [this was] looking at something that we all take for granted as an element of life that everybody can agree is a good thing, like we all love children and childhood, but then looking at it from a very outside perspective to gives you a very different perspective on what this actually is and what it could be. Maybe it’s because I’m obsessed with identity lately, but when I first read [“The Slows”] those controversial, almost shocking perspectives on something as important and beloved as motherhood and childhood was really interesting to me and I couldn’t get it out of my head.

Was it always something you had been interested in directing?

The minute I read it, I thought if I ever get a chance to step back into directing, this is the project I’d want to do it with because it’s grounded science-fiction, it’s about women and it is a world that just seemed really, really rife with possibilities. When I read it, I was at a place when I had been out of film school for a long time and my path to Hollywood was through screenwriting and I got lucky pretty early on in that regard, so I got further and further away from my directing roots to the point where the last time I was on a set was “Guardians of the Galaxy” and there were 700 people working on it. It was like a miniature city that had been set up and I was so impressed and enthralled, of course, but it felt very different from my very humble experiences of making movies in school, so I was hoping to do a short film that was science fiction that I could really wrap my arms around and feel like I could do a good job, really bringing it to life. I could’ve taken that short story and set it up somewhere [as a feature] — and whether or not it actually got made would be a different question — but it’s a project that I really wanted to be overseeing and in control of because it’s so important to me.

Cinereach seems like a world away from Hollywood, so how do you find them as a partner?

Cinereach was one of the most amazing and important experiences of my entire life. I can’t overstate the importance of having a foundation that’s also a production company really believe in your vision when you have never directed anything and they’ve only seen your screenwriting and the stories that you’ve told, but then basically say, “Anything that you need to feel like you can confidently step forward into this role as a director, we want to try and facilitate for you.” I almost speak of Cinereach like a person because it’s [taken on] this almost totemic importance to me, and they’ve supported “The Slows” from the beginning with a fellowship. The way that that worked was I was in New York a few years ago and I got a phone call saying that this production company that’s also a foundation wants to meet with me. I took the meeting and they didn’t talk to me at all about blockbusters or superhero movies. They wanted to actually know what kinds of stories I wanted to tell if I could do anything I wanted. And I said, “Look, I love blockbusters,” that’s my bread and butter, and I love genre movies, but I would love to tell something that’s a little more complex and risky and personal and this short story from the New Yorker has never left my mind.

A year later, they reached out and said, “Hey, we have this fellowship that is all about supporting the artistic vision of a filmmaker” and they had all these incredible alumni like Terence Nance, Eliza Hittman and Barry Jenkins and nobody really knew about it. It was really quiet and undercover, like a secret that I had stumbled upon, so I felt so lucky that they would even invite me to apply. I really had to put some thought into it, but I applied and interviewed and eventually I received some notice that I had been accepted and that was like a dream come true because I got to meet so many wonderful people and really be exposed to art and craft and inspiration that I hadn’t really experienced in a long time. It was really one of the most profound experiences of my life.

With that experience you have where you may not have to ever think about how much an VFX shot costs, is it difficult to conceive of a world this big on the budget of a short or does that experience actually help you figure out how to cut corners?

I feel like one of the things I took away from having such a limited budget on my short film when I’m used to not having to think about budget at all was specificity — just being really specific and intentional in every choice that you make. [For example, when considering] the objects that are on the desk of the person in this world, what does that say about this world? Would they have plants and [if so] would those plants be under glass or contained in some way? What’s their view on the natural world? So it forced me to make such specific choices about what I had available compared to if I was writing a movie with no budget, I could’ve just said, “Oh, there’s a levitating train that flies around the building” rather than, “No, this is a world in which the things that are organic and natural are fetishized, but they’re also something that’s not allowed to run rampant, so everything is almost like a bonsai tree. It’s all very trimmed and contained and controlled.” That lends to the film feeling much more specific in my mind and much closer to my vision rather than doing something a little easier, but might feel a little more familiar.

Thinking of the natural world, was Portland in mind as a location from the start of this?

Portland was one of these incredibly lucky [instances of] happenstance. Originally, I had been hoping to shoot in the summer so I’d have more flexibility in terms of daylight hours, but the more we started getting closer to fall for our production date, I started to realize the visual language that I was playing with was so much about greenery, but also the dead mulch and mushrooms and things that are decaying. There aren’t that many places in America that have both at the same time — you really have to kind of go to a rainforest for that — but Portland has incredible forests just an hour outside of town, so it ended up being a really lovely, auspicious [twist of fate] because the Portland film community is incredibly tight knit and so supportive and warm, it was just a wonderful experience. I lucked into it at first because I needed there to be greenery late into the year, but then it all worked out so well and I would love to shoot in Portland again in a heartbeat.

I couldn’t help but notice that Megan Amram, a writer/producer on “The Good Place,” happened to be in the background as one of the Slows and I assume there might’ve been other friends in the film. Did you bring in some ringers?

Yeah, that’s exactly right. My husband is one of the extras and my childhood friend Sara Gilman is the Slow who’s chopping wood in the background because she’s actually won wood-chopping competitions in the past, so I said, “Hey!” She lived in Portland, so I asked her to be in it. And Megan is from Portland, so I said, “Hey, if you happen to be in town,” and she said, “I’ll fly up, I’ll visit my mom and I’ll be in your movie,” so it just lent to this feeling of a convivial and warm set, even though it was physically very cold and raining the entire time. It was a very warm and supportive atmosphere on set, which I was surprised to hear is not usually the case. I’ve heard that sometimes when light is running out and there’s only so much you can do in a certain amount of time, things get tense, and certainly, there was a lot of pressure in that regard because the sun was setting around four o’clock every day and we had most of our scenes shot outdoors. But there was a lot of respect and a lot of kindness on the set and I credit Kyle Eaton, who was one of our producers that brought this incredible group of people together.

Yeah, it was one of my favorite parts of the process in terms of really having to think about the way in which you’re conveying a character and a purpose and an intention. I felt like I had to go and do a fair amount of work before I would be able to speak [to the actors] in a way that was the most helpful and of course all this preparation that I did ended up being totally unnecessary because my actors were such pros and we bonded right away. But I put a lot of thought into how to both respect all of creative choices that [the actors] brought to the process without resorting to what I had originally envisioned because everything that Breeda and Annet brought just elevated the material instantly. They gave me so much to work with and I learned so much from them.

How did you find Annet and Breeda for your leads? They’re both great, but I’m guessing certainly in Breeda’s case, you can’t put out a casting notice for the kind of unpredictable energy she brings to this.

We worked with Arlie Day, a wonderful casting agent in L.A., and we had a casting agent in Portland for the other roles, but when I went through the characteristics I was looking for [with Arlie], the very first person who was at the top of my list was Annet because she’s everything that character is supposed to be. She’s very refined and she also has this childlike innocence to her, but also this worldly look. You couldn’t put a finger on exactly what her particular background is because she has such an amazing heritage — she speaks a million languages and she’s very refined. The minute I saw her in “The Americans,” I’m like this woman has serious acting chops, so I was so happy she had a window during that time period [we shot] and she really just brought an incredible professionalism to the set. I will also say that Breeda knocked my socks off. I was so amazed by the energy that you put a finger on. She is an amazingly versatile actor and we just get along really well. She has great wells of emotion to access and she brought an incredible kick to the movie. I can’t even imagine the character of Greta now and not have it be Breeda.

Was there anything that came as a surprise during shooting that you may have in the film now that you like about it?

We shot the whole thing in four days, so we had a very short time period and the scene where the little boy is crying was a big question mark for me because I obviously wasn’t going to do anything that makes Walter, the young boy, cry, but we didn’t have a lot of time to wait for him to cry, so [we didn’t know] how is he going to play this scene. What ended up happening is his sister and one of the other young girls in the scene were playing with this doll and in the script, the boy is supposed to be upset that they are keeping this doll from him and he runs crying up to the main character Eryn [played by Annet], but what ended up happening was it was cold and rainy and Walter had to wake up very early that morning, so he just had reached enough. He was just done, so when he was crying, that was actually him just having an early morning and being tired and [when] we wanted him to come towards Eryn, we put his mother right behind Eryn, holding her arms out to him so he tearfully ran towards her. It ended up being a really beautiful moment, though my editor Ashley Rodholm had to do some pretty fancy footwork to make it work.

It sounds like you’re a born director. Given the ideas about motherhood in the story and the conversation around women’s control over their bodies, did the outside world influence where you may have ultimately landed with this film?

Yes, that was one of many things that went into conceiving this world. It was really important for me not to rest on any particular one side is good, one side is evil, even though both sides inflict violence upon the other side. It was really important to show that both sides had good points about the other side’s lifestyle and that neither of them were 100 percent wrong. I haven’t actually heard the perspective of women’s control over their own bodies yet, so it’s really interesting that you bring that up, but in addition to the question of whether to have kids or not [that I’ve heard], is what does it mean to be an occupying force if you think you’re doing the right thing or to choose to potentially open your children up to diseases if you think it’s more natural?

I’m a very passionate defender of reproductive rights, but there’s a lot of questions about what is natural, what is toxic — this kind of duality — and also [considering] people who are living [a certain way] and maybe we think that their lifestyle is bad or dangerous for their children, so do we have the right to go in there and take the kids? Does that show that we don’t understand the importance of that culture? There are these other issues of social services that come up when people watch this movie, and l find these all fascinating subjects and all very controversial because they resonate so deeply on a very personal level for everyone, but rather than coming down on any particular side, even though I am firmly pro-vaccine and pro-women’s abilities to control their own bodies, I really like probing these questions of what does the other side think and why. That’s what I was trying to do in a short film that’s also futuristic and filled with strange VFX. [laughs]

“The Slows” will play as part of the Genre Stories Shorts Program at the New York Film Festival on September 29th at the Francesca Beale Theater and September 30th at the Howard Gilman Theater at 9 pm.