It isn’t any ordinary elementary school where you’ll hear the Greek philosopher Heraclitus name checked at the door, but under the leadership of Kevin McArevey, the Holy Cross Boys Primary School in Ardoyne, a working class community in Northern Ireland, has become a very different place. Then again, Ardoyne itself is somewhat of a unique place to teach, serving as the site of numerous incidents during the numerous violent confrontations between the Catholic and Protestant populations that would come to be known as the Troubles in the 1970s, and the city continues to carry on the trauma from those incidents to the present day when physical violence remains a currency of choice and suicides happen with disturbing regularity. As Heraclitus once said, “Everything changes,” but still it’s one thing for McArevey to repeat that wisdom to his prepubescent students and another for them to take it in and apply it to their lives, which becomes the crux of a beautiful year-in-the-life captured by co-directors Neasa Ní Chianáin and Declan McGrath in “Young Plato.”

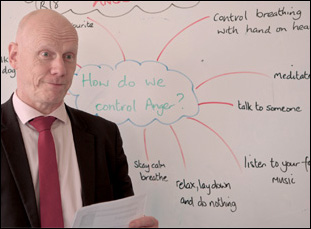

Having previously checked into an unconventional boarding school in “School Life” (co-directed with David Rane) where a pair of Bohemians mixed ‘60s pop into the curriculum with science and social studies, Ní Chianáin is able to once again observe the benefits of an educational path less traveled at Holy Cross where McArevey fills a white board daily with provocative quotes from philosophers and engages kids who may not even entirely have a grasp on language yet to express how they feel about the world around them. The principal, who has a soft spot for Elvis and would seem to put any of his own frustrations into his ferocious daily workout routine, isn’t flustered by either those that demur or actively show they haven’t been listening when a vicious playground fight breaks out, but more often than not “Young Plato” chronicles the calming effect that his lessons have when rather than holding their emotions in, the kids have a place to unburden themselves of what they’re feeling.

Reminded of where anger could easily lead if given the chance just outside the school gates where there remains barriers between the Catholic and Protestant communities known as peace walls where burnt out buses once stood as blockades, the boys at Holy Cross start to see how history doesn’t need to repeat itself in Belfast and while the progress will only last as long as students remain engaged, “Young Plato” warmly depicts how much impact educators can make on an entire community and the power of words that haven’t diminished over centuries. With the film premiering at DOC NYC, Ní Chianáin kindly took the time to talk about how she was drawn to making another film around education, dealing with the disruption of COVID and keeping her focus on the students while providing a larger historical context to the place they live.

I know. My partner says you should do one more school film and then that’s it, you’d have a trilogy. [laughs] But this was brought to me by my co-director Declan McGrath because he’s a Belfast filmmaker and he had worked as an editor for me years ago, so we knew each other and he knew about “School Life.” He had heard about Kevin McArevey and what he was doing in Ardoyne and he said, “Look, what do you think?” Immediately when I heard about the philosophy being taught to kids, especially in places as challenging as Ardoyne, I thought if this works, this is amazing. I was hooked and that was it. Luckily, they let us in and we spent two great years there.

When we spoke last, it was obvious what a challenge it was just figuring out how to cover an environment as sprawling as a school. Were things any easier the second time around?

Obviously, you know about a few things. I knew I needed to be really focused on who the characters would be, so my shooting ratio wasn’t as high as on “School Life,” but it was a little bit more difficult, because this was a day school and we only had access to [the students] while they were in school. Then COVID happened. There was complete shutdown, so it was more difficult getting access to the community and how to bring that narrative into the story. It was easier in some respects and funding-wise, but like every project, it’s a new adventure and it throws up its own stuff.

Was the school curriculum built around philosophy as much as it appears in the film or was that simply your focus?

Philosophy is not part of the school curriculum. This is an ordinary state school and the curriculum is the same as it is in every other school, but it’s what the headmaster introduced as a course subject to the kids and he brought in the oral history into those classes that we see where talking about the past [in Belfast], because he is all about, “Don’t accept the Republican narratives that are being passed down to you — question them, question violence. This is not the way forward.” He was seeing in the playground kids resorting to physical fighting and he was going, “This is the beginning of all of that. This is not the way to conduct yourself in life.” He was very much focused on how to recognize emotion and anger and anxiety and all the things that the kids were dealing with on a daily basis and try and get them to recognize it, and understand what it is, then figure out what those triggers are that set those things in motion.

It was also interesting how you could framed the community around this school with scenes from the town – those establishing shots don’t look like your usual B-roll, so what went into them?

Because I was new to Ardoyne and I hadn’t really known that area, what impressed me the most was that everything was walled and fenced and peace walled because Ardoyne is a Catholic enclave, surrounded by a Protestant or loyalist communities, so everything is sectioned and separated. Then the different areas are defined by murals, so you know when you’ve stepped over the line into a Protestant community because the flags are different, and the narratives of the murals are different, so that really affected me. I thought, “Wow, this is the messaging that these kids are seeing every single day” — of division and vitriol and war, and that informed how we tried to show that in the film using archive footage.

Ardoyne was famous for two big things — what happened in the burnouts in Ardoyne in 1969, and then what happened in more recent history to the Sister School of Holy Cross because it was just in a part of the neighborhood where you had to cross over into a Protestant neighborhood to get into the Catholic neighborhood and they tried to stop Catholics crossing, walking down this street. That all informed really what the lives of the kids in this school, because some of their parents would’ve been in the girls school, and it was trying to evoke the past in a present day observational film. I was very specific about what I was trying to show of what happened just outside the school boundaries.

For us, it was more like, “Oh my God, what are we going to do?” We did have a chance to review the material and we got an editor that started towards the tail end of the first lockdown, so we started the editor earlier, because we knew we had to extend our filming period. And for our last term of filming, the editor was already feeding us assemblies and we were able to say, “Okay, that’s going to work. We’ve got something there.” We were able to react to the edit, which was a very efficient way of working because we knew quite quickly before we’d finished shooting what we were missing.

Did anything happen during filming aside from COVID that changed your ideas of what this could be?

I was utterly shocked by the suicides that had happened that first Christmas. I was completely unprepared for that. We didn’t know that was on the cards. I knew that the Belfast did have a reputation in the past for high suicide rage amongst young men, but I thought that that had been in the past and we didn’t expect that we came back after Christmas, after the first term of shooting and five kids in the area had committed suicide. That just really focused us on the importance of critical thinking and the importance of parents and kids keeping the conversation open because everyone disappears down their screens now these days. People aren’t talking to each other anymore, so people aren’t checking in with each other. Parents may not know where a kid is at emotionally, because everybody’s so busy, survival at that stage. If your child is happy on playing Fortnite, they’re not acting out and the conversations stop, so that really highlighted the importance of talking things out and teaching kids to be more resilient about how to deal with their emotions.

An interesting element of the film is when you’ll occasionally bring in music to express what’s going on in some of the conversations with the kids when the words themselves are muted. What was it like figuring that out?

There was different reasons for that, and sometimes you don’t really want to bring what the child is saying out into the public domain either, but you get the gist and you don’t have to know the detail of exactly what was expressed, but you get the idea that something is being expressed, so you have to be very careful about what you reveal about a child and a situation, so you give them enough to understand what the subject and the way it’s going, but not give any details. That was how that helped.

What’s it like getting to the finish line and putting this out into the world at this moment?

We’re so excited by it. We’re going to go up to Ardoyne and do a screening for the community, so that’ll hopefully be a big celebration, but this is the world premiere, so we don’t know what people’s reactions will be to it. I guess nervous and excited? For me, I think if what Mr McArevey really does in his school became the norm in every school in the world, we’d been a very different place right now, so I hope people will see the power of critical thinking and I hope it’s embraced and people will make this part of the curriculum worldwide.

“Young Plato” is available virtually on the DOC NYC online platform from November 15th-28th.