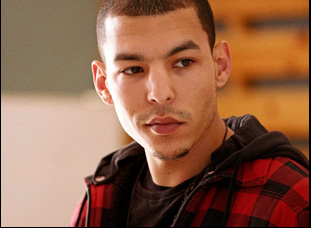

“It hasn’t been used for a while,” Anas (Anas Basbousi) is told by the headmaster at a cultural center in “Casablanca Beats,” introducing her newest instructor around the art school and he takes notice of the recording studio shrouded off to the side. It’s of particular interest to him when he’s come to the school to teaches classes about Hip-Hop, so adamant about it that he’s willing to sleep in his car rather than find a more suitable place to stay and not easily impressed when his students start spitting rhymes that sound even a smidge less than fully authentic. He knows from experience how cathartic it can be to have an outlet for his thoughts and feelings, and while he himself isn’t necessarily forthcoming with that information to the teenagers he’s teaching, he knows that asking them to be completely honest with their emotions about what’s going on in the world in front of them is a rare and special thing that’s well worth seizing.

If Anas is the one to shake the dust off the microphones at the school for the kids to express themselves in “Casablanca Beats,” director Nabil Ayouch has created a powerful amplifier with the enthralling drama, taking inspiration from the real-life students that have come through the art center he opened up in the impoverished Moroccan suburb of Sidi Moumen where he previously filmed “Horses of God,” which dealt with the events leading up to the devastating suicide bombings that took place there in 2007. Rather than seeing any anger and frustration channeled into violence, the film involves many of the students — as well as Basbousi, one of the teachers there — taking creative energy from their circumstances instead and making music together, fiercely grappling with all the pressure they face from a community with deeply religious roots and little economic opportunity. It isn’t just their experience that infuses their performances, but Ayouch also shows the class using their ingenuity to bring the world around them into their art when performances often take full advantage of what available props there are around, whether it’s a clothesline or spray paint, to turn the mundane into something beautiful.

After turning heads earlier this year at the Cannes Film Festival, “Casablanca Beats” has been selected to represent Morocco at the Oscars this year in the best international feature category and is making its North American premiere this evening at the AFI Fest in Los Angeles en route to a U.S. release via Kino Lorber. Shortly before the Stateside debut, Ayouch graciously spoke about why it’s especially touching to bring the film to America, the unorthodox production of “Casablanca Beats” that resulted in such naturalism on screen and creating the music for the film that’s bound to get the heart racing.

Actually, right after the shooting of “Horses of God” in that neighborhood of Sidi Moumen, I decided that I would not leave this neighborhood without leaving something solid and concrete for the youngsters that I worked with. I remembered how in my childhood in the suburb of Paris, a city called Sarcelles, it was quite violent and I somehow understood arts and culture was important in my background because at a cultural center, I learned how to sing and dance and watched my first movies. I probably would not have become a director without that center, so I decided to build this center in Sidi Moumen, [which is] where I shot “Casablanca Beats” years later.

The idea [to make a film] came from observing the youngsters of the center, especially a classroom called the Positive School of Hip-Hop that you can see in the film. One day, Anas Basbousi, a former rapper came to us and said, “I want to quit rap, but I want to keep transmitting it,” so we gave him a kind of wild card to do this classroom and I was listening to the courses and watch them on stage, and I found that there was not only talent, but also very powerful and meaningful words. After a year of observing them, I decided to sit with them and to understand where those words come from and their backstories, [like] where do they live and why? And I decided that it would be my next film.

Given how realistic this feels, there might be the assumption that many of the cast are playing versions of themselves, but I understand some of them are playing characters that are very different. What was it like casting this from who was available at the center?

The only thing I was certain of is that I would like to do this film with them and not with someone else because we spent a year together. And even if they’re nonprofessional actors, I wanted to go up to the end of the process with them because I was very much inspired by their personal stories and the reality that they experience every day. On that basis, I wrote a story that is close from that reality and close to the characters while some of them are far of what they are, but close to what they experience every day, and the idea was always to blur the borders between documentary and fiction and make everything true, so that we don’t feel the direction and the mise-en-scene in the film.

There is a remarkable energy in those classroom conversations where you probably couldn’t know what was going to happen next. What was it like figuring out how to capture that on camera?

I was in contact with my cameraman and with the teacher, Anas, by earphones, so I could direct the scenes. I also decided to give them some space for improvisation, so it was a mix of direction at a distance and also being very close to capture their true words.

Have you perfected a technique for working with nonprofessional actors to get such natural performances?

The most important thing that I always keep in mind is to be as close as possible from their reality. That’s what I want to protect — their truths. Because they all live around the center, as you can imagine, some of them in slums and they’re full of that existence and experience that I show in the film, so it was important that they don’t act, that they do as if the camera is not here. At the same time, they play a part and interpret a character, and I came from theater — I was an actor in France for a few years before doing direction — so we work like a theatre troupe, to push on the set and in the creation of every scene to always to be as truthful as possible, including Anas, [playing] the teacher. For example, one of the very last scenes [in the film] when we are in this room and he cries, that is something we shot over and over for 45 minutes to reach that result, where he can express, finally, what hurts him, and where there is this willingness of transmitting [where that’s] coming from.

Is it true you actually filmed this in separate blocks of time where you could edit in between and rethink things before moving on to the next part of filming? That seems like a real luxury as a storyteller.

The process of filming was actually a bit particular on this film compared to my previous ones. I said to my producers and partners from the very beginning that I didn’t want to shoot this film in one [stretch], the classical way, [where it’s] a few weeks or a month, and then it’s over. Since the very beginning I wanted to listen to [the students], to see their evolution during a long period and to be there with my camera, so the shooting lasted one-and-a-half-years in different parts during which I wrote the script, I shot it and I edited and then I rewrote and re-shot and re-edited. The whole process lasted three years because with all that material, I edited again and again and again, and in that process, as you can imagine, lots of material stayed and lots of material left. For example, all the incidents that happened in the film that I was not expected, at different level, different stages, I wanted to be ready to catch them, and they are in the film.

Did anything happen that really took this in a different direction or you could get excited about that wasn’t anticipated?

[Both] good and bad things as usual. we had a bad surprise during the shooting to see some parents coming in to take their daughter out of the center, which inspired one of the scenes that you see in the film. It was very sad, but in the same time, it gave me inspiration to go up to the end of the process and to integrate that in the film. The good thing I didn’t expect was that the dancing scenes would be possible to capture the way you can see them in the film, but with the help of the people at the center and the choreographers, who did a wonderful job, I did those dancing scenes exactly the same way I wanted to do them in front of the center.

There were two steps. The first was the words of the rap and the slams. I wanted those [lyrics] to come from the youngsters and their truths, so with Anas, the teacher, they wrote their own words based on their reality and then I asked Mike and Fabian to come to Morocco for residency that had to last two weeks to compose and produce the soundtrack and they stayed two months. [laughs] And everything happened in the studio [that’s based in] the center, and [Mike and Fabien] recorded some wonderful material and they took that in France back with them, and produced the soundtrack based on what they recorded in Morocco.

But [Mike and Fabien] come from Hip-Hop, and they worked with the biggest rappers in France — but also in the United States — and when they arrived in Morocco, they told me, “Nabil, what we see here is exactly what we observed at the beginning of the Hip-Hop in France.” Now it’s changed a lot, but in Morocco, it’s pure, it’s authentic and they took lots of pleasure to go back to their beginning period. And it was the same for me, because in Sarcelles where I grew up at the beginning of the ’80s, I remember the first sounds of Afrika Bambaataa, of Grandmaster Flash, and first breakdances in the streets [like the] Smurf, so [it recalled] how friends and I took that Hip-Hop movement to tell our stories through rap. I was very moved to see that in the Arab world, 30 years later, some youngsters are doing exactly the same, leaving the egocentric, bling-bling part [of it] out, and taking it as an instrument to tell who they are and their everyday stories — what harms them and what shocks them on topics that are very important to hear, not only in Morocco as you can imagine, but all over the world.

What’s it like getting this out into the world now?

It’s a particular moment after the year-and-a-half year we’ve experienced [collectively]. The good thing is that the film is full of the energy and the positivity of those youngsters, and I think it’s good for people to see an optimistic and positive movie right now, especially when it comes from the youngsters from the Arab world. We are not used to hearing beautiful stories from the Arab world concerning the youngsters, and it’s important that their message — what they have to say about society, religion, and tradition — and the way they express it with such a huge faith and hope in the future is heard all over the world, especially if we come to the United States where the Hip-Hop movement was invented.

“Casablanca Beats” will screen at AFI Fest in Los Angeles on November 11th at 8 pm at the Chinese Theater at Hollywood and Highland, with Ayouch appearing for a post-screening Q & A. The film will be eventually released in the U.S. by Kino Lorber.