There’s a scene far removed from the Texas Renaissance Faire fairground in episode two of “Ren Faire,” Lance Oppenheim’s engrossing and irresistibly entertaining three-part series, where a rare bit of quiet contemplation stands out amidst the chaos that George Coulam, the founder of the park, seems to thrive on. The octogenarian has bought himself some peace on his 200-acre estate where he wakes up to the same Enya song every morning and takes a stroll through the garden of palm trees and lotus flowers, the yield from the brilliant idea decades ago to take a page out of Walt Disney’s game plan for his Florida theme park to set up a similar site in Texas where the octogenarian is in complete control as the landowner and mayor of Todd Mission, a town that may only have 121 permanent residents but brings in tens of thousands of tourists annually looking for an escape to the 16th century. But he seems far more in his element when taking on the pandemonium of presiding over the operations that run the gamut from parking lot attendees to turkey leg vendors and likely gets more joy from seeing a phalanx of employees joust for his attention than the knights that so many others come to see on the premises.

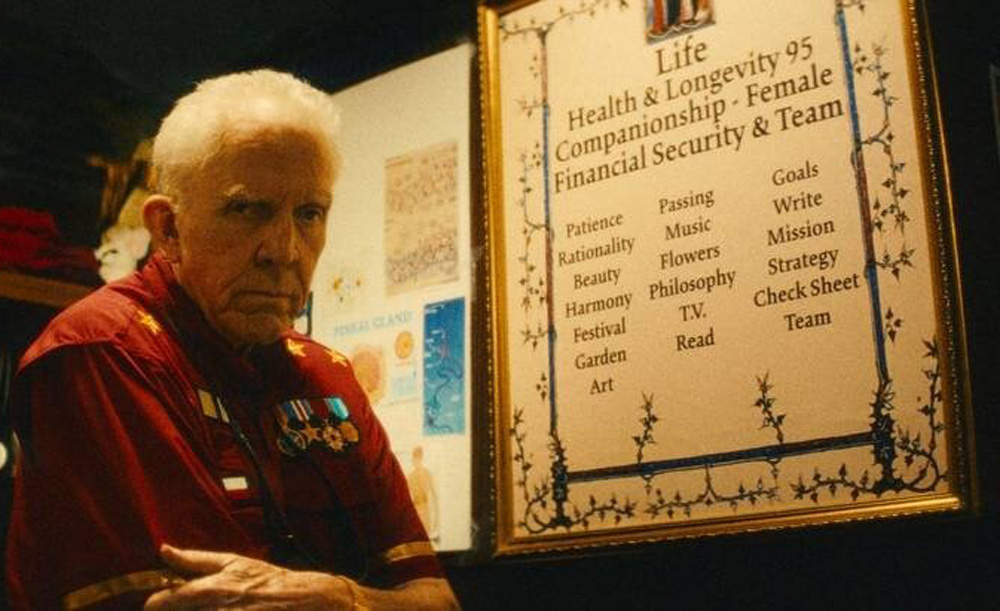

However, Coulam seeks pleasure elsewhere, lured outside the limits of Todd Mission to an Olive Garden hardly befitting of a such a successful entrepreneur after listing himself on a Sugar Daddy Web site, to sit down for endless breadsticks with Poe, someone at least six decades his junior, and suddenly he doesn’t look all that commanding. She may have flown all the way to Texas for the promise of his money, but as he pokes around wondering whether she has natural breasts, you suspect she’s the one who holds all the power. It’s a scene other filmmakers might’ve been inclined to leave on the cutting room floor when it isn’t directly part of the monumental struggle for control over at the Texas Renaissance Faire, where longtime general manager Jeff Baldwin, the park’s kettle corn baron Louie Migliaccio and vendor manager Darla Smith all have put in a bid to run the business when Coulam believes he’s only got a decade left to live, but as in all of Oppenheim’s major works so far such as “Some Kind of Heaven,” there’s always something elusive to chase for even those who seemingly have it all.

That includes the viewer who will be left wanting more from “Ren Faire,” not because Oppenheim and crew have left any loose ends and pack every frame as densely as possible to resemble the feeling of stepping into the amusement park, but because the series is so utterly riveting, inevitably drawing comparisons to “Succession” and “Game of Thrones” when tucked in between seasons on HBO, yet really unlike anything you’ve seen before. As the filmmaker trains his lens on the behind-the-scenes machinations to take Coulam’s throne, a literal prospect when his mansion is a model of Henry VIII-level decadence and he is as fickle to his employees as that six-time married king was to his wives, there is a disarming empathy towards everyone involved in such a silly situation when their very human needs have brought them here, some having no choice but to bend at the knee of Coulam when beyond their livelihoods being dependent on his approval, there seems to be no going back after investing so much of their lives into building up the attraction for him and Coulam feels as if he owes it to himself to leave his legacy in the most capable hands, having no natural heirs of his own.

When Oppenheim comes across as a polar opposite of Coulam in every way, noticeably quick to credit collaborators that help create such immersive experiences rather than see himself as a king, “Ren Faire” is approached with a type of curiosity that is constantly revelatory, where the colorful array of file folders in the boss’ office come alive with the priorities and history that they hold and the menial work of employees can be seen in service to their larger aspirations. Although we recently spoke for “Spermworld,” his other grand achievement of 2024 now streaming on Hulu, the director generously wanted to keep the conversation going about getting the level of tactile and emotional detail he does in his work, finding the right framework for a multi-episode series after two features and his crucial first audience for every project.

With this one, it was different than anything I’ve worked on before because unlike “Spermworld,” “Ren Faire” was like a result of really active investigative journalism that happened concurrently with the production. “Spermworld” really started with Nellie Bowles sending me a draft of her article and I helped poke around and research and then I went off and made a film and she saw the film when it was done. On this, David Gauvey Herbert and Abigail Rowe, his researcher, came to me with the idea of making something about George [Coulam], this man founder of the Renaissance Festival and also the mayor of the city he created around the fair and they also were with me on every single day, almost, over 100 days of production, talking to people, helping me break really story and guiding me to the things I should be shooting and helping get things into focus. Having someone there to help with that was invaluable. Then it was my job to figure out in cinematic terms how to express that.

What was it like actually filming on the grounds? I was just transfixed by like those scenes of the kettle corn being stirred.

Being there was this extremely overwhelming experience. Every single part of every senses is being hammered literally by so much different stimuli. There’s the smells, there’s the sounds, there’s people in front of you that are engaging with you. There are costumes. Everything it gives your brain, it was easy to overload. But it that amount of sensory engagement was also very inspiring in a way where it allows people to escape, which is why I think so many people love going to Renaissance festivals to begin with, and stylistically, that was really inspiring [to think] how do I make something as overwhelming as the experience of being at a Renaissance Fair?

In terms of the actual practicalities of how we pulled it off, it was painful. It was a lot of days in the beating hot sun. Nate Hurtsellers, my cinematographer, literally carried the camera on his back. There’s so much shooting and physicality needed to actually shoot this thing, and moving around the fair itself was also very difficult. We were shooting with a steadicam through these massive crowds and on the weekends when the fair was going on, there’s upwards of 80,000 people that are there. The park itself attracts almost 500,000 people on an annual basis, so it was amazing to see the cinematic excess in front of you, knowing that it was right there to capture. But then when it came time to actually turning on the camera, booting it all up, being hydrated and well fed enough to not be too exhausted to do this, the challenge was then how do I capture that? It took a lot of time to figure it out.

It was a fluid process. The first year we were there, we were not prepared enough at all. We would dread having to shoot those fair days just because of all the pyrotechnics and logistics involved, and even just the fairgrounds themselves are just so massive, it’s so easy to get lost. Bathrooms — there are plenty there, but depending on how far out we were, it’s not necessarily that easy to get to, especially when you’re lugging very heavy equipment. We had no idea what we were getting ourselves into and it never got easy, but by the time the third year rolled around, we were well equipped and psychologically better prepared for what to expect. It almost was like we were suiting up to go into battle and we knew what we needed just to pull it off. But the reality is that a lot of the corporate drama of the series really takes place in the off-season, so that was a lot more manageable on my crew than the fair days.

Knowing your process a bit of reengineering situations that have already happened, what was it like bringing some of these people back together after there must’ve been so many rough feelings? The stakes are never low in your work, but usually they’re personal rather than business.

I look at each film and they’re all very different from one another, and I remember when I was making “Spermworld” at the same time, I always felt like both projects had different challenges. With “Spermworld,” I knew that the material was extremely emotional, but then the question was how to make it entertaining and get people excited to watch something like that, and with “Ren Faire,” I always thought that it was a very entertaining story, but how do I access the emotions and get deeper into the internal stakes? That’s really when you start to buy into what’s going on there. It’s not who wants to be king of the Renaissance Festival. It’s what are these people sacrifice in order to achieve this quest? And maybe through understanding that a little bit, you’ll identify with them and the story doesn’t just become about a succession crisis at a Renaissance Festival.

It actually becomes something much deeper. It’s about work in general and the experience of really being in a toxic workplace, which I’ve been a part of before in my past. I’ve done jobs where I had difficult bosses that I also was hoping would respect me in some sort of way and I know what that feeling is like and that way each person in this — Jeff, Darla, Louis — they’re all very relatable, I know people that are maybe not as eccentric or iconic as George is, but certainly fit that bill of being controlling and oftentimes impetuous, mercurial people in the workplace that demands the world from you and ultimately when you give them that world, they don’t think much about that.

It was a totally different experience working with Jeff than any other person I’ve ever filmed with. I remember working a lot with the folks in the Villages [the retirement community in Florida for “Some Kind of Heaven”] in the acting club, and I feel like Barbara maybe has some similarities to Jeff in the sense that both are very theatrical and they are performers at the end of the day and [their presence in the film is] almost similar to like a method performance where the events and the emotions that they are experiencing are real, but the way that they play to camera is different than I think anyone else in a documentary film.

Jeff said something in the first episode [of “Ren Faire”] about this show he was in called “Daddy’s Dyin’ Who’s Got the Will,” and he wasn’t a method actor, but his father died in the middle of rehearsal [for that show], so he took that experience into “Daddy’s Dyin’ Who’s Got the Will,” and the emotions that he experienced were then real and I remember when he said it, it just unlocked everything — the way I thought I would engage with him as a person, but also as a performer in this high-octane corporate drama of a film that ends up reaching very operatic heights later on. The way Jeff shows his vulnerability is beautiful, and it was truly for me impossible to just not fall in love with him and how giving and trusting he was, but also how artistic and artistically inclined he was in wanting to make something that wasn’t just a documentary, but also captured the immersive dimensions of the fair.

Did you know about the three-episode structure going in or did this find its natural length and chapter breaks?

No, I was terrified. Essentially what happened was I went and I shot about eight days-ish worth of material and made a sizzle reel out of it that. Elara Pictures gave us the resources to make that. From there we took it to HBO, and I knew at the back of my head that ultimately if I wanted to make something present tense and extremely active and as cinematic as I would need to, the resources that I would have to have probably would only be afforded to me if I made this into a serialized show, so we pitched it as a three-part series, but what we thought would happen was totally different.

When we finally were able to receive HBO’s backing, I was absolutely terrified. I had no idea what I was doing or how it would unfold. Every day just so deeply stressed. And then eventually I had to just shake it off and just focus on what was happening before me and I had an incredible team of two editors, Max Allman and Nicholas Nazmi, who are just astounding. I’ve credited them as writers because their assimilation of real life into something that feels as intense and thrilling as this is. The work they did on this is unbelievable, and it’s their fingerprints that made it as just beautiful and engaging as it is.

Working with Ari is just an absolute joy because Ari is a storyteller at the end of the day. He’s never working to picture for the most part. He’s taking ideas and people’s situations, and he’s making music trying to trace that emotion, and on this, he engaged a much larger canvas. There’s music in almost every single moment of this whole show, and there’s hours on hours of footage and hours and hours of scenes that are in this. I think there’s 35 tracks that are actually on the soundtrack for this, but there’s hundreds of other tracks that he made exploring ideas.

We were very interested in this old Hollywood/Bernard Herrmann “Vertigo,” “North by Northwest” sound for George, [speaking to] the lonesome king. What does that sound like? The other dimension of this was how do we [incorporate] a lot of the sounds that exist inside the Renaissance milieu? There were these people using these flutes that played sound effects on them that almost sounded like the Looney Tunes sound effect when you’d see like the Roadrunner crash into something and there’d be a ball of dust. That led us down a different rabbit hole, which Looney Tunes in general, tracing the absurdity of the world and finding a way to make that musical and fun and feel like this rollicking circus that you want to go to. Eventually, that becomes like entrapping like this merry-go-round that eventually burns down, so there was a lot of experimentation involved.

Ultimately, the feeling of power and proximity to power and what power does to you when you have it for that long and also what it does to you when you don’t, but you desperately want it so badly — those feelings are how Ari makes his music. He’s a genius, really, and such an emotional, empathetic person that he can take the experiences of these people and craft this feeling that gives the whole work this novelistic dimension that I think wouldn’t be there otherwise.

It came together so beautifully and I was listening to a recent interview you did on The Best Show with Tom Scharpling that I had to pick up on – is it true that your mom serves as a first pass and a bit of a BS meter on all these projects?

My mom is amazing. She’s an attorney, and I wouldn’t say we have the same taste whatsoever in art or film, but she’s an incredibly supportive person. And also, as a Jewish mother, she shows her love through concern and judgment at times, so in that sense, she’ll get very upset with me because so much of my life for the last few years was wrapped up in making these films. She would get upset if I wouldn’t tell her what was going on in them and eventually she would want to watch the cuts of them. At first, I would be very resistant and [she’d say] “I’ll just be supportive and I love you.” But eventually, it actually was very helpful and I really I seek her feedback now because of the way she watches things. She’s not a filmmaker and her favorite movies are rom-coms. She exposed me to “The Twilight Zone,” so maybe we have that in common, but in terms of a story like [“Ren Faire”], there are so many gears it’s operating on and there were many cuts of this that were just indiscernible and it made sense to me and [my editors] Max and Nick, but it wouldn’t make sense to my mother. So I remember any time she would have trouble understanding something, we had to fix it.

It was always like a test audience in a way, and my mom represents a cross-section of a very intelligent viewer and someone who reads voraciously, probably resembling something like the classic HBO viewer. So I used to be embarrassed by it, but I love my mother very much and it’s very fortunate to have someone who cares so much.

“Ren Faire” premieres on HBO on June 2nd at 9pm and episodes two and three air on June 9th and available thereafter on Max.