At the recent premiere of “Deerfoot of the Diamond” at the Camden Film Festival, Lance Edmands was aware he’d have competition for audiences, having grew up in Maine and knew of the unspeakably beautiful late summers spent on the coastline.

“The weather was so good, it was hard to go in to watch movies because it was so nice to be outside, but it was a really great, positive experience,” Edmands said of the homecoming. “One of the programmers Ben Fowlie helped me connect with [“Deerfoot” producer] Adam Piron in the beginning because they had done some work together, so it was really a perfect place to [premiere] it and it’s a great venue and a really cool festival.”

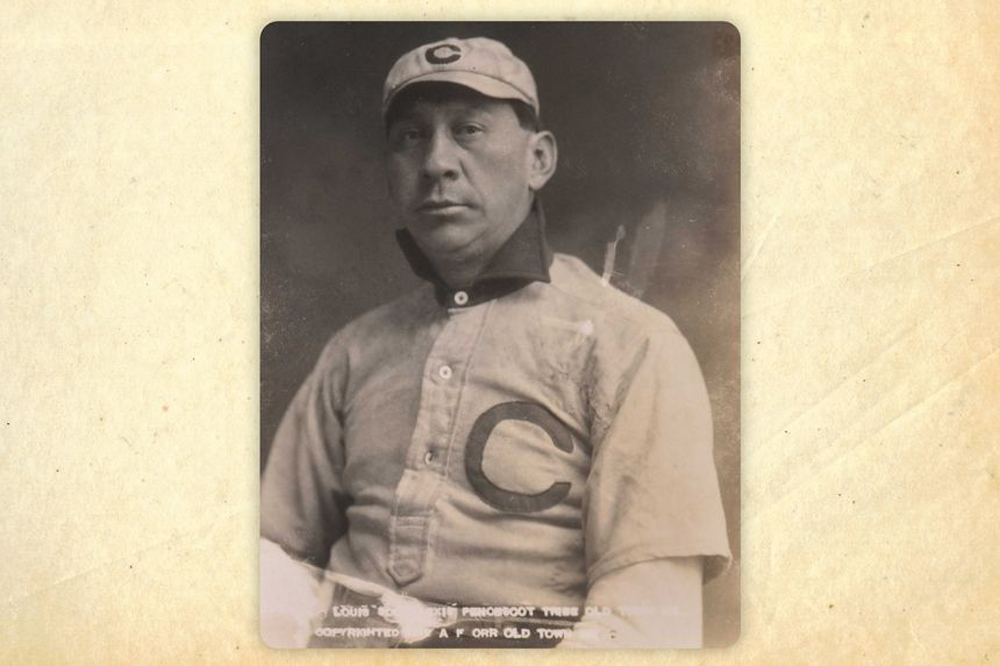

As it would turn out, there was as much fresh air inside the theater as there was outdoors when Edmands and the team behind his latest doc have uncovered a relatively little-known bit of baseball lore in telling the story of Louis Sockalexis, a member of Penobscot Nation who became the first Native American to play in the major leagues. While Sockalexis spent just three years playing for the Cleveland professional baseball team from 1897-1899 when they were known as the Spiders, he became a sensation for his lightning speed on the field, leading to all kinds of nicknames and eventually leading sportswriters of the day to dub the entire team the Indians, a moniker that would last over a century. Whether that was a tribute to Sockalexis’ talent or intended to disparage was a question that Sockalexis had to grapple with himself and hasn’t been resolved in the years since as “Deerfoot of the Diamond” dives into the controversy surrounding Cleveland’s decision to change their team name to the Guardians for the 2022 season after decades of mounting public pressure.

When debate continues to rage on into the present, it’s only fair that Edmands pulls Sockalexis into the current context as well, considering a life in which his value as an athlete superseded race until it didn’t, as he would find the same sports reporters who celebrated him ultimately attacking him with their pens after an ankle injury derailed his career. With tasteful recreations and insights from Sockalexis’ own recollections recovered from the period, vividly relayed by “Malni-Towards the Ocean, Towards the Shore” director Sky Hopkina, the film honors the fact that the ballplayer continues to make history when refusing to consecrate his legacy in the past. With the film arriving on ESPN this week while it will continue to grace big screens on the festival circuit, Edmands spoke about what it was like to stumble into discovering such a rich subject, constructing a shoot that could enhance what relatively few archival remnants there were during this period of early baseball – and cinema – history, and the collaborations that yielded such an affecting portrait of a man and his times, as well as the ones we’re living in right now.

How did this come about?

I essentially came across the Sockalexis story while I was researching an entirely different project that took place in Maine in the timber industry around the turn of the century. Through that research, I discovered a little bit about Sockalexis’ work in the woods because he was a logger late in life. He had been born and raised on the Penobscot Reservation in old town Maine and I’m a huge fan of baseball and a big fan of Maine — those are two of my greatest passions and joys coming together, so I went out and purchased on the biographies of Sockalexis and while I was reading [them], it came up in the news that the Cleveland Indians were going to change their name to the Guardians. The Cleveland team name had been traced back to Sockalexis as being the inspiration and I thought it was an incredible coincidence that I was discovering all this simultaneously and at that time, ESPN had reached out to me to see if I had any ideas for sports documentaries. I had been fascinated by this story, so I pitched it to them and they came onboard which gave us the resources to start doing the research as the final year of the Indians was being played out and it [became] the first year of the Guardians, so it was the perfect timing to make and release a film that looked at Sockalexis and celebrated his history and his contribution to the sport within a new context.

This is the first archival based film you’ve worked on. Is that a different way to build a story?

With every project, I’ve tried to do something different and I’ve worked as an editor on a number of projects that involved archival, but I never directed one that had any archival element to it, so I was excited and I got really interested in the idea of trying to find images of Sockalexis that weren’t widely available. Through that process, I learned about archival research and there are only a handful of images of him that exist, so I was determined to find them all and get it out there as part of the film and that’s [also] what led us to the recreational footage that we did that’s suggestive of the era. We tried to bring him to life a little bit, which was a challenge because obviously he died so long ago and there’s no moving image of him that exists and maybe two or three interviews with him that were done by newspapers at the time. When he was in jail, he was visited by a reporter and a lot of those excerpts we decided to bring into the film to try and get his voice in there as much as we possibly could.

It’s hard to know who he was as a person and what he was like as a character because so much is written about him but he didn’t really get to tell his own story or there’s so little through his voice, so that was a big challenge – to have some feeling of him, trying to conjure him up in some way that felt a little more alive than some old stock photograph of him.

Sky Hopkina does a great job of giving him voice and he’s just one of a number of great Native American filmmakers who worked on this. What was it like putting together a production team for it?

Yeah, I knew since I’m not from that community and not Native myself, I needed from the very beginning to involve the tribe and then have Native representation and Indigenous representation in front of and behind the camera as much as I could, ESPN was very much in support of that, so the first person I reached out to was James Francis, the historian for the Penobscot, who helped me reach out to the tribe and make inroads there. That’s how we ended up working with the tribe and shooting on tribal land – they had other people approach them about the story before and were sensitive to someone just showing up and taking a story as their own and not involving the family or the tribe in the telling of that story, so that was important.

I also reached out to Adam Piron, one of our producers, who is a great Native filmmaker who runs the indigenous program at Sundance. And when I was talking about how to bring the voiceover to life, he suggested Sky because in his [own] films the voiceover is very hypnotic and poetic and drives a lot of his own work and I thought that was a great idea. I was really happy he agreed to record that for us and we were able to build a good team that had some Native voices in it and create a sense of trust and that hopefully helped balance the story out and tell it again differently because the first time people were writing about him, it really was a bunch of old cigar-chomping white guys from the big newspapers making up crazy stories and it was important to try and ground it.

I know the story alone took you in an entirely different direction, but was there anything you came across in the research or during filming that changed your ideas of what this could be?

The hardest part was deciding what to include and what not to because there’s so many interesting stories and a lot of tall tales or myths around him that weren’t in the film. I also wasn’t sure if I was ever going to get to speak to anyone [in the Cleveland organization] about the name change and what discussions they had with the Natives in the area or how they came to that conclusion. I was hoping to understand that a little better, but I was never able to get the team to engage with the project and that was a little surprising on some level because I wasn’t trying to rake them over the coals and accuse them of systemic racism, even though that was definitely a part of it. I was surprised at the degree to which it’s still a hot button issue in Cleveland. There’s still a lot of disagreement and consternation about it and I wasn’t expecting necessarily that there would still be so much sensitivity around that.

I thought you captured it well and you mentioned the recreations, which are so seamlessly integrated I’m not sure I would’ve known they were in there, except for how little availability there was of cameras at that time. What was it like to set those shoots up and adhere to the shooting style of the turn of the century?

Some of that early baseball stuff from the early 1900s is unused material from Bill Morrison, who has worked in the experimental world and has created a lot of found footage films. It’s hi-res 2k scans, and really beautiful in the way that it’s degraded and I wanted to use that as a template for how to go about filming the recreations. We did a lot of testing early on. We tried some Bolex cameras and some hand cranking stuff. We settled on 16mm as a way to get as close as we could to that look even though it’s very difficult because the chemistry and the lenses and the cameras are all so different now. But we shot it on film and there’s vintage baseball groups that play with 1800s rules and they play with the old bats and balls and it’s like the civil war reenactments but it’s baseball, so I found this team in Cleveland called the Cleveland Blues, so their uniforms are actually shockingly accurate to what the uniforms were back then when Sockalexis was playing.

It was perfect because we had all the uniforms, we had a team and we basically used them as actors for that [recreation] material and it matched the era closely. We got another team involved. and we staged some moments we needed for the story, just to tell certain aspects of it, whether it was that home run [Sockalexis] hit at the Polo Grounds or the moments where he was sitting on the bench in his downfall era. We also shot in Cleveland at a park where they have several buildings that they’ve maintained to be historically accurate to the era and they’re basically like sets, so we basically had a backlot. We had a very small budget and it was a documentary, but we were able to find these perfect people and places that fit the era and just try and see [Sockalexis] moving and bring him to life a little bit. It was super fun to figure it out and I worked with DP Matt Clegg and a colorist named Mikey Rossiter who helped set looks and add some grain and some other texture to it so we could get as close as we could to that look of Bill Morrison’s footage.

It sounds pretty organic to the process, but one of the great qualities of the film is how you weave together a Sockalexis biography and a present-day consideration of how this history is hardly over with. Was it difficult to balance the two?

That was always part of the concept — to collage the film a little bit and have it exist in the past but also in the present simultaneously. As far as the ESPN “30 for 30” series, I just found out this is actually the oldest story they’ve ever told – 1897, so I think it really incredible that 120 years later, his name is still being evoked and discussed when it comes to ideas and expectations around traditions in sports and how you actually honor someone and native American mascots and conversations that are still pertinent and relevant to today. So it was always the plan to reach into the past and draw out all those parallels to the present day where a lot of those same struggles and problems are still going on.

“Deerfoot of the Diamond” will premiere on ESPN on September 27th at 8 pm and subsequently stream on ESPN+.