On the eve of a final parole hearing for Michael Thompson, Kyle Thrash and cinematographer Logan Triplett were in the living room of his extended family as they were mulling over what the next day would bring. Even for those who had been too young to ever meet him before he went to prison 26 years earlier, Thompson meant a great deal, a former GM factory worker in Flint known to be a productive and generous member of the community who turned to selling marijuana in the ‘90s until he was busted by the local authorities. Although attitudes towards low-level narcotic changed around the country in the decades that followed, his sentence did not, a stretch of 42-60 years seen by many at the time as an excessively harsh penalty after police tied his ownership of a gun nowhere near the scene of the crime to maximize the punishment, and as Thompson neared his seventies with a final appeal for clemency on the line, the family made an appeal of their own to the skies above.

“There’s things that obviously happen in documentary that I think is what makes the medium really strong where you’re able to be around a moment that feels really intimate and we just kind of put the camera in the middle and Logan started turning,” says Thrash, who could crouch alongside Tripplett for a prayer circle that becomes of the most arresting scenes in “The Sentence of Michael Thompson,” which he co-directed with Haley Elizabeth Anderson. “It was something that I felt like we were lucky to be a part of and capture.”

Thrash, Anderson and Tripplett captured far more in the 26-minute short, which is told largely through the eyes of Thompson’s daughter Rashawnda Littles, who remains hopeful in all things as her habit of playing the scratchers at the local convenience store attests and the impending birth of a granddaughter only adds to. Still, the odds seem stacked against her family’s chances of seeing Michael back at home, even as everyone from prosecutors to public defenders rise to his defense trying to get the attention of Governor Gretchen Whitmer to grant him his release and the filmmakers track the galvanizing campaign within the community to gain Thompson his freedom once more. After a rousing recent string of premieres at the Santa Barbara Film Fest and South By Southwest, where at the risk of spoiling the film Thompson may have been around to hear the applause, Thrash took the time to talk about the importance of bringing attention to the case as well as getting to know his subject’s family and capturing the ripple effect that the unfair sentencing has had on them.

How did this come about?

I was approached by the nonprofit The Last Prisoner Project, [who had] said, “Here are some stories. Do you think maybe we could work together on something?” They didn’t have anything in mind, but when I looked at the work they were doing in terms of all these people still incarcerated for non-violent cannabis charges, it felt like a story that needed to be told, trying to put a face to the statistic that 40,000 people are still incarcerated for this. When I found out about Michael’s story and started talking to him, we really connected and I felt like his story epitomizes the injustice that’s occurred through the war on drugs in America. I had found the story and I felt like I wanted to put together a diverse team with different backgrounds that could tell this story from an authentic place and I reached out to Haley, whose short film “Pillars” I loved and felt like it would be great if she wanted to collaborate on this. She loved the story and felt like it’d be something that’s worth telling and [we thought] hopefully we could do a good job in telling his story to bring about some awareness to this topic.

The way the film is set up, you come in through the family, but it sounds like you met Michael first. What was it like forging that relationship?

The nonprofit introduced me to Michael and Michael and I talked for months. This project really started as trying to advocate for Last Prisoner Project and try to bring awareness to them and it led me to becoming close with Michael and trying to help him in any way I could, whether that was with my producer Ian Ross, calling the hospital to try and get the right food because he’s diabetic and Michael got COVID in prison for a little bit and given his age and his health issues, we were very nervous for a little bit there.We [were] speaking through a lot of hard times and we were recording these phone calls and one of the things I was proud of with the project was in June 2020, we launched an animated video campaign to bring awareness to his case [where] we used some of the phone calls that appear in the film that went pretty viral. Tens of thousands of people wrote the governor and made phone calls to bring up his parole hearing and get a date, so it happened pretty organically and we obviously grew into becoming good friends.

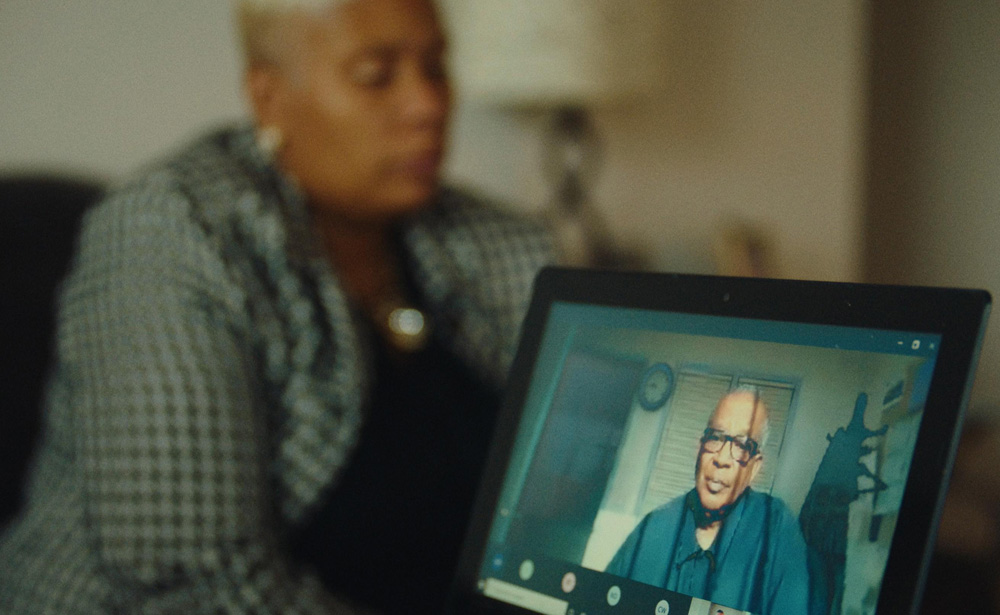

Ultimately, the use of sound is quite effective in the film – I’m thinking immediately of that shot of Michael as he’s frozen on the screen and you hear others discussing his fate during the parole hearing. Did that shape your approach to this when physical access might’ve been difficult to come by?

Yeah, I knew that a lot of what I was going to be recording was going to be these phone calls that I was having with him and also this public hearing, [which would] usually be behind prison bars where there are no cameras allowed, but because of COVID, it was able to be on a Zoom record, so we were able to hear all these voices. The Michigan Parole Board said they had never seen so many people show up to a public hearing before there were so many people that wanted to speak on Michael’s behalf. That’s what led to hearing all these people advocate for Michael and say why it’s an injustice and speak on his character. Michael’s nephew is actually the mayor of Flint, Sheldon Neeley, so he came and spoke and [Dana Nessel] the attorney general came and spoke out on his behalf, which never happens. David Leyton, the prosecuting attorney, got behind Michael’s clemency application — these things just don’t happen and a lot of that came from that grassroots advocacy to put the pressure on the people in power to take another look at Michael’s case because he had been denied clemency twice before, so this was his final chance to be able to get it. Because of a lot of people making those phone calls and bring awareness, we were able to get him out.

Rashawnda emerges as the film’s central character on the outside. What was it like getting to know her?

Yeah, Rashawnda and I started having phone calls and she has such a big heart and she wears her emotions on her sleeve. I found this person that cared a lot about her father and I also found it really interesting that she likes to play the lottery and I felt like she’s someone who was always looking to change her life in a dramatic way. Her life wasn’t the way she wanted it and a lot of that had to do with her father not being there, that had taken a toll when he went away, so I tried capture that when someone is incarcerated, a lot of times that incarceration affects all family members, not just the person that’s incarcerated. But I love Rashawnda and getting to know her was really special. We continue to have a relationship and she’s a really wonderful person.

The shooting style of this is so evocative – did the 4:3 framing come immediately?

Haley, Logan and I talked a lot about strong compositions and a lot of it is shot on sticks [whereas] a lot of Haley and I’s work before this had been handheld. We both like realism and creating energy in that way, but for this, we really wanted it to be still. A lot of it is listening to these case details and these phone calls that are being had and the wide lenses and these static compositions allow for a meditative experience at times. It allows you to listen for the details in a more impactful way. Then lighting [came] in terms of the cold Flint winter and seeing the Flint water tower in the beginning, which is obviously an American injustice, just like Michael’s sentence, so we were trying to frame the Flint landscape in a cold, static way.

Does anything happen that changes your ideas of what this could be?

What was difficult was not knowing if [Michael] was going to get released, so my producing partner Ian Ross, Haley and Logan, the DP, and I had meetings and always talked about what would happen if he wouldn’t get out. Obviously, that would’ve changed the trajectory of the film dramatically and there’s some relief in his family now that he’s able to be home and be back in their lives, but obviously the sentence that was given to him and his family is going to have lifelong consequences. Having some sort of resolution at least shows that people do have a lot of power and they can put a lot of pressure on these public officials to bring up these cases and look at cannabis again as it is legalized, so we were at least provide some hope for people that we can make change.

What’s it like getting it out into the world at this point?

It’s great. Michael was in Santa Barbara and in Austin [with the film], so being there with him has just been really surreal and incredible. We were able to be given the special jury recognition for our poster and Michael was able to give a speech at the awards show for SXSW [where] he ended up getting a standing ovation. It was very profound. This whole experience has been very humbling and I’ve been very grateful. To see him on stage at South By, my heart was very full on that day for sure, so it’s been great being a part of this with him.