After a few years spent with his head down, deep into research on documentaries about Gordon Parks (“A Choice of Weapons”) and Robert Stigwood (“Mr. Saturday Night”) where he could at least have the benefit of traveling without having to step foot outside during a pandemic, John Maggio finds himself with quite the social calendar this week, trying to balance out visits to a retrospective of Parks’ films at the Anthology Film Archives in New York and the premiere of “Mr. Saturday Night,” following up its recent premiere at DOC NYC with its release on HBO.

“What’s funny is with the latter half of Gordon, it’s the same time period – he’s making “Shaft” around that same time [as Stigwood was making “Saturday Night Fever”], so they kind of live in the same world,” says Maggio, laughing about whether it’s better or worse to have two films come out at around the same time. “But I love it. You spend so much time making them and crafting them and I love talking about them. I find them endlessly fascinating.”

Maggio’s enthusiasm for his subjects is infectious and he’s right to be intrigued, particularly in the case of Stigwood, a somewhat enigmatic impresario who ruled over the 1970s as the manager to its biggest musical acts on earth such as The Who and The Bee Gees. But his Trojan horse for true world domination was “Saturday Night Fever,” a film that Stigwood designed around ingredients he knew were going to be marketable – a killer soundtrack and a fresh-faced John Travolta, known at that time as only Vinnie Barbarino from “Welcome Back, Kotter” – but no idea how to mix them together. Relatively new to the movie business when his most significant experience was convincing clients Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey to make a movie out of “Tommy” when they said “no” to so many others, Stigwood set about engineering a blockbuster with a bunch of fish out of water, whether they were coming from the music industry such as music supervisor Bill Oakes or entirely new to the entertainment industry as a whole, such as assistant Kevin McCormick, who stumbled upon Nik Cohn’s chronicle of his adventures at the 2001 Odyssey Discotheque in Bay Ridge for New York Magazine and optioned it at a time when few thought to turn articles into movies.

As memorable as the movie would become with Travolta strutting down the street to “Staying Alive,” it turns out the making of “Saturday Night Fever” is equally engaging when Stigwood parted ways with original director John Avildsen on the eve of his best picture triumph with “Rocky” when he wanted to ditch The Bee Gees tracks and had to quell tensions between the star and the film’s eventual helmer John Badham over how the dance scenes would be shot. However, Stigwood is seen as a visionary who saw the opportunity growing to incorporate original pop music into films and pioneered the use of a soundtrack as a promotional tool, fueling a resurgence in disco when it was thought to be dying on the vine and “Mr. Saturday Night” gives one the feeling they’re right alongside the producer on the wild rollercoaster ride. Maggio, on a bit of one himself this week, kindly took a moment away from the hectic schedule to talk about how he came to focus on Stigwood for the feature that’s part of Bill Simmons’ ongoing Music Box series, creating a doc out of archival imagery and footage that could come alive and how he could get incredible access with audio-only interviews he wouldn’t have had otherwise.

It’s funny because Bill Simmons from Ringer reached out to me after he’d seen a film I made called “Panic” about the 2008 financial crisis that I did for HBO, and he said, “I’d love to work together, what do you want to do?” And I said, I’d love to make a music film, so we started just kind of spitballing ideas. I was always interested in The Bee Gees and one of the things Bill and I talked about was not doing a root-to-ball biography of a band, but come after it from a little bit different angle, so I started looking at Robert Stigwood and I’m like, “He managed The Who and [Eric] Clapton and Cream, [some] of my favorite bands, and oh, he also did ‘Tommy.’” Suddenly, this whole body of work emerged from this one guy and I thought I’d like to know more about him and it seemed like a great vehicle to tell the story.

It just so happens that in that moment from ’70 to ’80, [Stigwood] couldn’t not make a hit. He just really was hit after hit, both on Broadway and on the radio when he decided to turn his attention to Hollywood. He had a vision. He could see it like a chessboard in a way nobody else could see it. It started with [John] Travolta. He thought Travolta was going to be a matinee idol and didn’t have the project for him yet, but signed him to a three-picture deal without any pictures and he had “Grease” in his backpocket, and he saw that synergy between the music soundtrack and the movie and how to really capitalize on the youth culture that was emerging after Woodstock. In my experience in Hollywood and in other industries, there are very few people who don’t know if something’s a hit until it’s hit or other people think it’s a hit. Stigwood had a great sense of smell and he did it.

Between the era itself, which must be pretty hazy to those who really lived it, and Stigwood being an elusive figure, was it difficult to get interviews?

It really was all over the map. Creatively, I wanted a couple things — first, to hear only from people who had lived it, who had been there and experienced it, either on the moviemaking side, who had experienced Stigwood or experienced it from the club 2001 perspective, and [second] I didn’t want to shoot on-camera interviews. I wanted people to be almost encased in amber in that way, to just be immersive. We experience them as they experienced it – young Travolta, unbelievably handsome and graceful in those dance scenes and you just want to drink it up – so those creative decisions I made early.

Then tracking people down to get their voices, I did phone interviews with people and in some ways, it was easier [because with] COVID going on, bringing a full camera crew to somebody’s house was not [possible]. And I worked with great archivists who really unearthed some real gems for us, especially of Stigwood because Stigwood, while he lived an outsized life — he loved Rolls Royces and threw big parties — he was a publicly closeted gay man in the ‘60s and ‘70s, and I think his friends knew, but that affected his public persona. That’s why I think he was a little bit in the background, so it was definitely tough to draw a picture of him and for a good part of his life, he had a drinking problem. At the end of the film when you see him alone on his giant yacht – it’s bigger than a yacht is even meant to be, alone and eating his sausages with HP Sauce, I think there’s a sadness at his soul that I don’t think was ever talked about. He was private in that way. So he was tougher to draw a bead on, but everyone else, especially Kevin McCormick, a young development guy at the time [who later became a major exec at Warner Brothers], had never made a movie and was suddenly tasked with making “Saturday Night Fever,” he was very helpful. I talked to him a lot on the phone about this great story of firing directors and finding the right cast and paying bribes. It was just a crazy story.

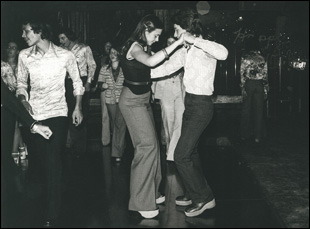

I had been aware of Nik Cohn, who there could be a whole film made on — one of the godfathers of rock criticism and music writing, and a great storyteller. I had done a series many years ago “The Italian-Americans,” [about] first generation Italian-Americans, so I was aware of the enclaves of Bensonhurst and I had met people back then who would talk about Nik Cohn having made up this whole story of “Saturday Night Fever,” so I thought how interesting. If I could only get Nik Cohn to talk to me about this.” And it took a while and a lot of convincing. He’s not a very public person, but I tracked him down in upstate New York and we would just talk on the phone about music. I think I had to gain his trust that I was a music person and I was going to do this story right. And I only did an audio interview with him, but I find his story endlessly fascinating. He was so in tune with disco, [which] as we say in the film was largely underground and largely black music and it wasn’t until 1975 when “The Hustle” came out that it suddenly exploded onto the mainstream, which is the death knell really of any cultural thing. But Nik was there before that. He always seemed to be in the right cultural moment.

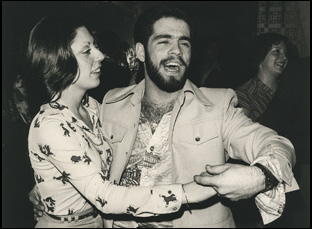

Then meeting Jim McMullan, the photographer and the illustrator for that [New York] magazine article, I thought his photos were so brilliant and he talked about the longing you see in the dark club when you turn the lights on — I got turned on by all of that. As an Italian-American too, I understood the machismo behind it and yet also the idea of wanting to express yourself, that yearning to get out, and I thought all of that teen angst was so beautifully articulated in Jim’s photos and Nik’s prose, so I wanted to introduce people to that backstory. Maybe I did it too much, but hopefully people will connect to it because I think it’s a universal feeling about being a teenager and all of that stuff that people go through. It’s all there encapsulated in that article and that’s something that Stigwood picked up on, he smelled it.

In telling an archival film like this, I’m always looking for those textural qualities and I love the contact sheets mixed with full-screen, mixed with full portraits and then the color film. [The idea came] after meeting James [McMullan] and going to his studio. Again, we didn’t shoot anything. We just talked and we got to know each other. He comes from that great New York Magazine era of Clay Felker and the Mad Men where it was super high design and his watercolors were a departure from that. In the midst of all those bold things that were going on in New York Magazine, there were these florid watercolors that he was doing because he grew up in China — a fascinating story than I didn’t get into, but then when he showed the original photos that he took that he based those paintings on, I thought what a great marriage we could have between those two and see the different depictions. To me, it brought home the ennui that he experienced in photographing them, that you don’t feel in the florid portraits that ended up in the magazine. I wanted to denude it in a way, strip back that color and really represent what was going on. What’s funny is had they been color photographs, it would’ve been different, but there’s always that level of abstraction with black and white, so when you see that rendered in color in the movie, it adds yet another dimension.

You also get the idea of momentum from choosing archival material from moving vehicles to establish a sense of place rather than stationary shots from Hollywood or London or where have you. Where did that come into the mix?

Again, it’s just motion, and there are things you can do in a great New Yorker article or in print that you can’t do in a film, but there are a lot of things you can do in a film that you can’t do in print. When I work with authors, I tell them I paint in broad strokes and in doc, there’s only so many different alleyways we can go down, but [we try] to create that energy in context. And I love seeing period cars. It just drops me into a sense memory of like, “Oh, I remember. My family had a black ’77 Caprice Classic.” That draws me in emotionally the way you can’t in a magazine article, so to see those moments outside of the Beverly Hills Hilton where you can imagine the studio manager who was talking about driving the tapes [for “Saturday Night Fever” to the record company] and seeing the bumper sticker that said, “Disco Sucks” and he’s got this disco film sitting next to him, I lived in L.A. for years, I know exactly the strip he’s talking about and you see the old billboards.

It’s all about connecting with people emotionally and those little bits of archival do it. It’s like the low hanging fruit of working with people’s old home movies. You draw so much emotion from people when you show home movies, even if they’re not yours. I find if I see any piece of home movie, I’m instantly transported back to my own childhood, even if it’s something from the ‘40s or ‘30s, so I find all of those little moments are really important. My editor Seth Bomseand I think a lot about how to evoke and create that emotional connection to the material and it can happen in those interstitial moments.

Yeah, I know it’s a Billy Crystal film, but I said, “Forget it. I don’t care. He really is Mr. Saturday Night.” [laughs] “Mr. Saturday Night” encompasses so much about Stigwood and that moment. When you think about timing, he’s working with Barry Gibb at that moment, who can also not not write a hit. Everything he wrote at that moment from ’76 to ’80 were pop gems. And with Stigwood – he’s got “Evita,” “Jesus Christ Superstar,” “Tommy,” “Grease,” “Saturday Night Fever,” the Bee Gees, Clapton…he had it all. There was nothing in that moment that he wasn’t doing that wasn’t a hit, so he put those two guys together and it just seemed that alchemy to me in that moment was the story. There are probably other stories to tell about Stigwood in London in the ‘60s – it’s fascinating, almost buying the Beatles and all of the stuff he was involved with, but the other thing [about “Saturday Night Fever”] was it’s just this cast of young kids trying to figure this out with Stigwood directing them, bankrolling it and telling them to go out and make this and if I sat in a bar with Kevin McCormick and some of the other guys [telling me this], I’d think, “That is a great story.” That was the bit I wanted to tell.

“Mr. Saturday Night” will air on December 9th on HBO at 8 pm and streaming thereafter on HBO Max.