There are other ways that the men director Jenifer McShane follows in “The Quilters” could spend their time, working off their prison sentences at the South Central Correction Center in Licking, Missouri, but the filmmaker finds them fussing over every detail of the birthday quilts they stitch and send to foster kids in the area.

“[The sewing room] opened at 7:30 and [they’d] stay until it closed at 3:30 and these guys are there every single day,” said McShane, who has long had a compassionate eye towards those who have gotten themselves in trouble with the law, from “Ernie & Joe: Crisis Cops,” her 2019 feature about a pair of police officers looking into less aggressive tactics to deescalate when mental health is a factor, and “Mothers of Bedford,” her 2011 doc which explores the impact of incarceration on families. “There’s a lot of things that I could talk for hours and hours about [in terms of] how we can make our prisons more humane, but I saw this as just a lovely way to humanize the story and who’s actually there.”

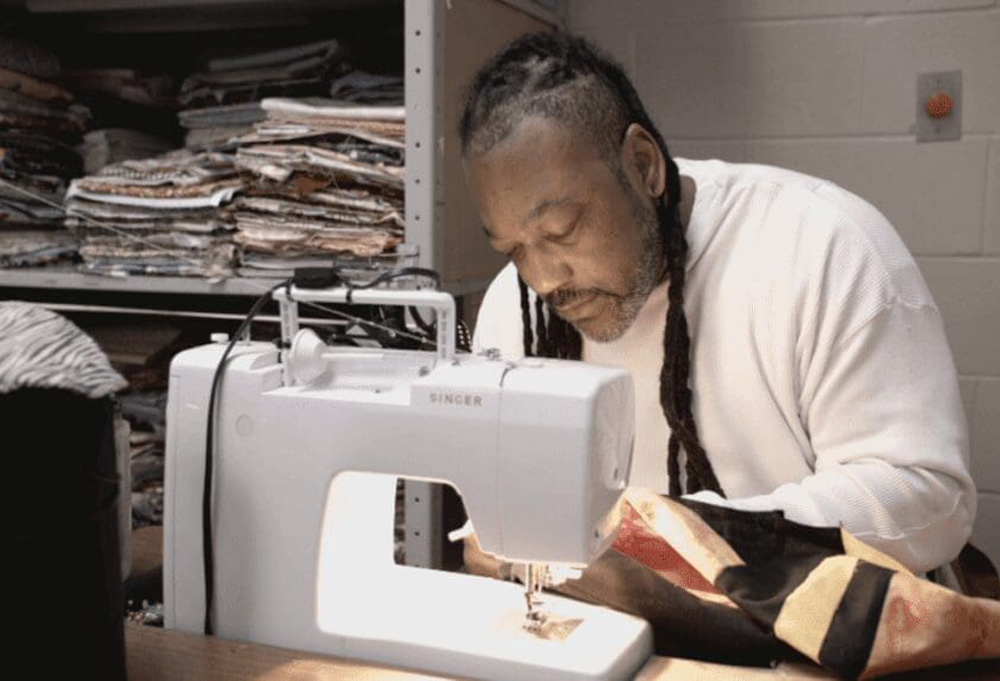

It was time well spent by all as McShane witnesses the fruits of a restorative justice program set up inside the maximum security facility where big, muscular men in the prime of their lives can look like little old bespectacled ladies, hunched over their sewing machines, eager to get every detail right on their ornate quilts. With fabric donated by the local community, they take what’s available to them and turn them into beautiful tapestries, a fair analogy for the transformation that appears to be happening as they invest themselves so fully in the work, unable to see the responses of the people they’re making them for, but nonetheless push ahead with the thought they’re bringing some joy into someone’s life.

While they put dozens upon dozens of hours into a single quilt, they offer that same gift instantly to McShane in “The Quilters” as you come to see people like Chill, Jimmy, Fred, Potter, Jeremiah and Rod come alive as they speak about their newfound passion, made all the more resonant with the knowledge of where they’ve been. The half-hour short is bound to move many as it premieres this week at the DC/DOX Film Festival in Washington D.C. and it was a great privilege to speak to McShane about getting to know these unlikely seamsters and we have the additional honor of exclusively unveiling the film’s poster, with our interview just below.

How did this come about?

Somebody sent me a short piece done locally in Missouri about quilting and this sewing room, and they just forwarded it to me and said, “This sounds like you,” which I thought was funny. I read it and I thought, “Oh, they’re totally right. “It does sound like me.” [laughs] I love stories that are unexpected — every one of my films, I think, has that quality, so I called up the prison and asked if I could come out without the camera, just to get a sense of what was really going on.

I was really taken with what was happening there. It was like those posters you see of a little flower growing out of cement. That’s how I felt. [The quilters] were just so passionate about what they were doing. They felt [quilting] was really healing and it was this imaginary bridge to the outside world in terms of doing something positive and feeling pride, which you don’t often experience when I’ve visited other prisons. And I’m sure you don’t feel it in other parts of the prison, but in this sewing room, there is definitely a sense of pride, so I left that visit and thought, “Okay, I definitely want to tell this story and I’m going to try a short because I’ve never done a short before.

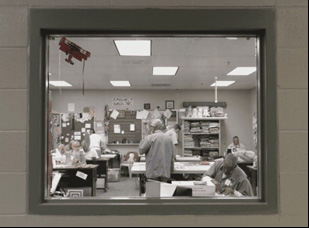

Yeah, it was. One of the men says, “We’ve created a community within the larger prison population,” and there was this sense that this was a special place. But I remember showing a rough cut early on to some other filmmakers and they said, it felt like this protected special box that they were in and you did feel that way when they were in it. [The room] was very collaborative. They were helping each other and it was a really interesting response to this idea of toxic masculinity, which we hear so much about, especially in prisons. So I thought the window was a beautiful image [where] we’re getting this glimpse into this different world that we don’t expect, and on some level, they don’t expect until they’re living it. A lot of these guys never sewed before, so it’s a real leap for them and then they find it very meditative and calming. So there’s a lot of layers to it. And I did love that window very much. Every time I was there, I shot different variations of that window shot.

The film really does allow you to meet the quilters as who they are now before becoming aware of their history. Was it a challenge to figure out how to structure this?

That was actually very intentional. I made a decision very early on that I wasn’t going to delve into their crimes and why they were there. One film can’t be all films, and I had a very specific idea about this film being about the healing nature of art in a place that you wouldn’t expect it, so that’s why we meet them as quilters and obviously I talk about their sentence, so there’s some sense of reference. Some of these men are not leaving, potentially, [with] life sentences, so that was context to understand that they’re finding purpose, even though there’s a good chance they might not be out again.

And I think it’s important to delve into other issues around prison, but I felt like this was a different kind of film, so it was very intentional that I stayed in the sewing room, except for some visits into their cells because I was exploring that new discovery that they are having as being seen as something else [which] goes back to that sense of pride. The care that they took concern they took for really doing a beautiful job [on the quilts] was obvious to me. Even though they don’t actually meet the recipients, they really wanted to hand off the most beautiful thing they could, and many of them have never sewed, so I just thought it was a beautiful snapshot and for a group that are often forgotten.

How long did you actually film for?

I visited the prison four or five separate times, and I tried to stay multiple days so that I became a fly on the wall and I was really trying to show particular quilts being completed. So if you’re paying attention, you notice some of the quilts we see again and again — Fred’s ’60s quilt, Chill’s butterfly quilt — I had to time it so that I was trying to get them at different stages of those quilts. But I also wanted to hang around long enough so that they really had a chance to relax and open up about how they felt about things. I didn’t do a ton of sit-down interviews, but I really wanted to kind of capture them doing what they love.

Yeah, it’s funny you say that because they were so upset about it and it also happened on the heels of Fred being asked to leave the program, so there was some sense it was a good thing was because it was a great illustration of the care and concern. Ricky was so concerned that they not send this [quilt] out to someone not as perfect as it could be. Also Fred clearly was a really well-respected member of that sewing room, and it showed how hard it is to keep your head together in that kind of environment.

Did the main people you follow like Fred and Chill immediately come to the fore?

They did and they all brought something to the table. Potter is a very new inmate and [the others] are showing him the ropes — he’s never sewed before and he’s learning from the rest of them. Chill was very wise about what he had learned and was pretty demonstrative about his feelings and how he felt he had changed. Ricky is kind of the Energizer Bunny — he just doesn’t stop. He’s really the one who fixes all the machines and teaches most of the men to sew that haven’t sewed before. He’s been there for decades and he is not sure he’ll ever get out, so the fact that he has found this sense of purpose is an interesting takeaway. I learned that in another film that I made about women in prison [“Mothers of Bedford”] that we all need a purpose and it actually doesn’t matter where we are. Even in the worst circumstances, you need a sense of why you put your feet on the ground and get out of bed.

Was there anything that happened that changed your ideas of what this could be?

I wasn’t quite prepared for just how collaborative [it was] and how much concern and love they have for each other. They really were constantly helping and supporting each other. It felt like a beehive. There’s this sense of collaboration where they’re very busy individually on their own projects, but the collective is so important to them. It really is this community. And at one point, Chill says, “We grabbed a hold of this and others don’t necessarily do that.” so it matters a lot to them, and they do love each other.

It’s interesting – that quote really struck me too.

When he said it, there were so many times when they were saying something and I thought, wow, they have really been changed by this — their inner sense of why they’re here, what they’re meant to do, how they may be seen differently, and they’re making something beautiful and then giving it away. That’s pretty powerful and that level of commitment and love was a little unexpected and beautiful to watch.

“The Quilters” will screen at DC/Dox as part of the Shorts Program: “With These Hands” on June 15th at 12:30 pm at Johns Hopkins University’s Bloomberg Center.