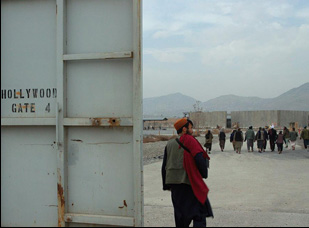

Despite its title in reference to its setting, you can’t believe that a film is being made at “Hollywoodgate.” A former CIA base that was abandoned in Kabul when American troops were withdrawn from Afghanistan in 2021, it was promptly repopulated by the Taliban forces that retook the country when international support vanished. Although the mere sight of any images from the country can be revelatory when international media is rarely allowed in as observers, the surprising observations that filmmaker Ibrahim Nash’at makes as he follows around the rarely photographed Taliban foot soldiers rummaging around the leftovers around the base, from shells of old computers to signs announcing that it’s two bucks to take a beer from the fridge, turn more shocking when he starts to learn there might be far more dangerous items that might still remain on the property.

As one of the men Nash’at observes says to another about what the documentarian is working on, “It is like a movie with real people. And if his intentions are bad, he will die soon.” Nash’at could only be made aware of these casually chilling comments later when there were limitations to what he could understand in a language other than his own as well as what he could see and hear when the Taliban limited his access, although nowhere near as much as one might suspect after the surprising decision to let him in in the first place, a portrait of present-day Afghanistan that proves as eye-opening as the 2017 film “Of Fathers and Sons” about its neighbor Syria made by his mentor Talal Derki, who against all odds embedded with a radical Islamist sect to show how extremists justify violence and maintain patriarchal control with misguided religious beliefs. Whereas one could witness there a generation of young boys being radicalized, Nash’at shows in his debut feature how those beliefs persist in the plans to remake Afghanistan when Taliban rule has once again goes unchallenged, with only fleeting glances of women and children in the film reflecting how they really are rarely allowed out of the house in the country and discouraged from any activity beyond their religious obligations. In their place, the Taliban can roam around with impunity, perhaps not appearing too dangerous when it looks like they can only fantasize about the things they want to do when speaking to one another, but when Hollywoodgate begins to look like it could become a working airfield with the resources already available on it, the film extends a stark reality beyond what the camera immediately captures as the Taliban starts to recognize their capabilities.

After premiering at the Venice Film Festival last fall,” “Hollywoodgate” is now making its way to American theaters and while in Washington D.C. for DC/Dox, Nash’at generously took the time to talk about how he gained such remarkable access to bring such reportage to the public, the influence of Derki, for whom he got to know while co-editing his most recent feature “Under the Sky of Damascus,” and what he came to understand about the footage he shot well into the edit.

The reality of knowing that the moment something ends, the news doesn’t really go much there anymore. It becomes part of the past and considering this, and the imagery that was coming out of the airport [in Kabul] with everyone falling off airplanes and the fear in the eyes of the people really put a fire inside me. Talal Derki was with me at the same time, and knowing that he’s did “Of Fathers and Sons” and took such a risk before ignited something in me that if he’s could do this, we could also do this one. With that in mind, I decided to go [and attempt to make this] and what made me think it’s possible is that I’ve done journalism for around 10 years and I filmed a lot of people in power. That has allowed me to pitch them that we are the ones that they should film with, but that also has given me the confidence that when I go there I am not just someone small, but for them this is someone that they want to work with. I thought that they would be interested in me because I’m also Muslim also, but what was really interesting to them is that I [previously] filmed people in power.

Could Talal prepare you emotionally for what it’s like to go into this kind of shoot? I have to imagine it’s very isolating.

Of course we spoke a lot about it and I was emotionally prepared. I’ve saw his film [“Of Fathers and Sons”] and I was really highly affected by it and then getting to know him and understanding how he did it was something that [I learned while] we were sitting and working on his latest film that he did with Heba [Khaled], “Under the Sky of Damascus,” so we already have had one-and-a-half years, [with] both of us stuck in one room for the edit. That’s how we spoke about all of these things before even the story came to my mind [for “Hollywoodgate”] and when it came to my mind, there was already somehow pre-preparation for it.

You’ve said you actually narrowed down the number of people you followed in the film in the edit for “Hollywoodgate.” What was it like to suss out a story from the footage you shot?

I actually I had five characters that I filmed with, and what we figured out after two or three months into the shooting is that the story is about the weapons more than anything else – these weapons might work [that were left over from the U.S. troops stationed there], so let’s follow the story of the weapons. Then when the weapons story kept developing, we were [asking ourselves] what is related to the weapons story. I was just filming them and I expected that they will fix two rifles but all of [a sudden] we’re trying to fix airplanes and while I was shooting even I never have thought that this is even possible. When I was going to the parade [the military had to show off the base], I was expecting a fun show and even in the edit, we were making sure that it has this feeling that starts as a fun show and then no, this is not something funny to watch.

At that stage, it wasn’t me alone. I was supported [in the edit] by Talal and Shane [Boris], who were both co-writers, and also Odessa Rae, the producer, and Atanas Georgiev, the editor of “Honeyland,” who was our main editor. We also have Marion Tuor, who I edited Talal’s last film with [as an editor], so it’s a [tight-knit] group of collaborators and we were also supported by Sahraa Karimi, the executive producer, and we had a story advisor and a full team of translators, so it was really a collaborative environment from the beginning till the end. Everybody involved in this was saying this seemed impossible in the beginning to have such a huge amount of people that are all sitting [around in scene after scene] and for us, it was more important that it represented all of us.

Because of the translation situation – and you must’ve been assigned one on the ground by the Taliban – was there anything you learned while processing the footage later that was surprising?

The live interpretation does not really bring you the core of what’s being said. I first had a translator from the Taliban and I replaced him with another guy who was really amazing. He started to be really involved in what I was doing and I told him “whenever you hear bad talk about me, don’t translate.” I could trust him a little bit more and he was doing live interpretation, but because it’s a lot of men talking, he was just [conveying the] main topic they are talking about and he would really help me [like] “Hey, this guy is saying this. Put the camera on him.” He became a line producer by the end [of production], and we had to pull him out [of Afghanistan]. He’s now living [elsewhere], but he helped a lot on the ground. [Then] we had a team for around nine Afghan translators in Berlin, led by Hewad Laraway, a brilliant mind from Afghanistan who’s our story advisor, and that team translated all of the 220 hours of material. We were really in deep conversation and they participated in [crafting the story by saying] “Hey, I’ve translated this part. This seems important,” so they would draw our attention more towards things rather than just translating, so it was very collaborative.

This may have happened organically, but as I assume you experienced yourself, there are very few glances at life outside of the base and you can really feel the domination of these men in power when there’s little footage of women and children. Was that something you were conscious of in the edit?

Of course we had no other option, but we wanted to make sure that the topic is conveyed and we were focused on the topic of them because it’s part of the reality of Afghanistan. But also in the world of Afghanistan, women are only have this free movement and being out as much as they want only if they are beggars. Other than this, there are a lot of restraints on them and this is what we tried to show. Women are present within the words of the men — they talk about them like “My wife was a doctor and I stopped her from being a doctor.” “Women are like chocolate if it gets touched.” These kind of things [that reflect the attitude of] “this is how we see women in the world” or as beggars in the street.

It was surprising to me to learn that part of the reason you were allowed to film was because they understood and accepted this to be propaganda, and even then it surprised me to think they honored that agreement given what you captured. Were you surprised that you were allowed to leave the country with this footage after all was said and done?

Not lying has helped a lot. I told them “I want to film you for one year and whatever I will see, I will try to show. I’m not going to try to make you heroes or make you villains. I’m just going to show what I saw.” And for them, this wasn’t lying and [from what I was told] most of the people that approached them were always trying to be sneaky and [they told me] “You don’t seem to be sneaky.” Until the last day, I was always saying the same thing, but again they were euphoric in the beginning — they were welcoming journalists and once there was a chance of flying, they started to close the door and I was already inside. I was the only one as they told me — maybe there is someone else, I don’t know — but I was the only one that is inside at such time and I didn’t come out, so that makes a difference. I think if I went there 10 days later than what I did, I wouldn’t have gotten access. They were new in the place and somehow I was part of this new regime. I’m very blessed to have been there in the right time in the right moment.

You’ve said that keeping access was more difficult than getting it in the first place. What did that actually entail?

It was more [a feeling] of “We’re tired of you. Get out of here.” They started to limit media and control it [much more as time went on] and [for me] it was like, “This guy is having too much access. We need to stop him.” I would be really persistent and I would go with the translator and we kept trying with many other ones until we found someone that is willing to help, and [we’d] talk to some other person until the access is gained back. At the beginning, it was access that was relaxed, but [as the filming went on], it became, “Okay, we will let you film for two days this time. We’ll let you film for one day.” It became much, much more controlled, like “When are you done? It’s over.”

I imagine this is a lot to carry with you for the past few years. What’s it been like as it’s started to get out into the world?

I’m very thankful for all the support that we’re getting from the industry. We’ve been in many festivals and we’ve been given some awards. People really believe in it, and it might be a lot of festivals that one has to go to, but I’m really happy in every country I go to, I get to meet people and interact with them and keep reminding everybody about Afghanistan. It’s important to do that at a time when the broadcast media has decided that Afghanistan is no longer of interest and they are forgetting about the daily suffering of the Afghans.

“Hollywoodgate” opens on July 19th in New York at the IFC Center and July 26th in Los Angeles at the Monica Film Center.