In many ways, it’s fitting that one of Halston’s signature creations remains a bit of an enigma, although there appears to be little to the design at first sight. A sleek, willowy slip that expressed the freedom of the era it was created in during the ‘70s, it was just a single piece of fabric with one very well-positioned incision, the kind of creative precision that you imagine what Leonardo Da Vinci might’ve been thinking of when he famously said, “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.” This is emphasized by the fact that when a version of it, laid flat as if it were a prized piece of cowhide, inauspiciously hangs from a wall in back of an interview for Frédéric Tcheng’s new biography of the fashion designer, it would be easy to mistake it for an oil painting. While the filmmaker can demystify how Halston did it to some degree by providing the context for the inspiration behind the style, he reveals another mystery – that anyone else thinks they could do it themselves.

“Carl Epstein would say to me, we had the patterns and some of the fabrics, so we could recreate any of these garments,” recalls Tcheng, of an interview he did with the exec at Esmark, the company that ultimately held the rights to the Halston brand, decades after such attempts to replicate his work had failed. “And I’m like, ‘You don’t understand. These are museum quality, unique pieces. You don’t recreate a Renoir painting just because you have a photo of it.’ That’s just not how it works.”

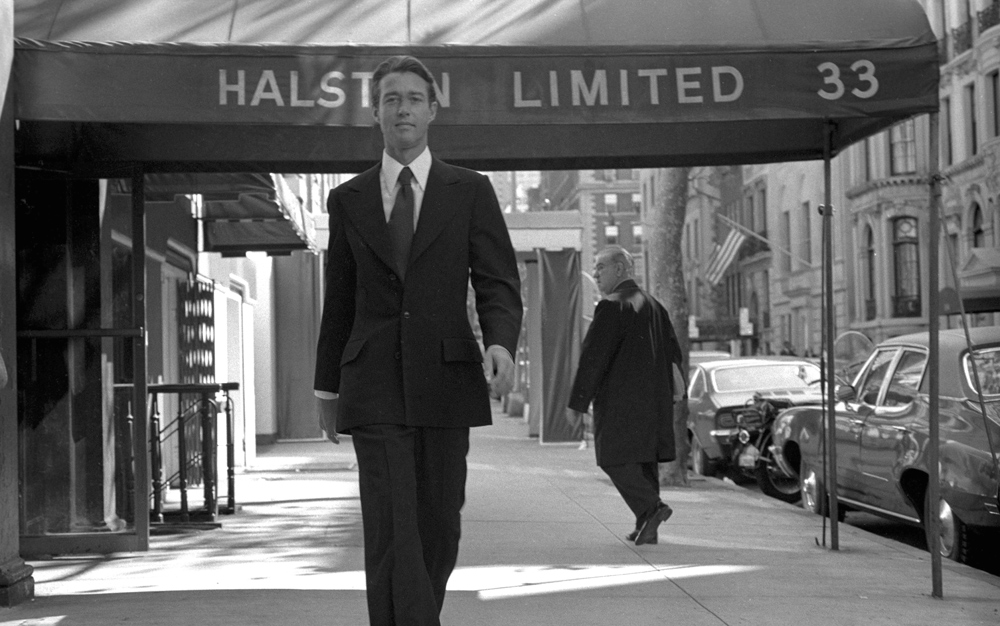

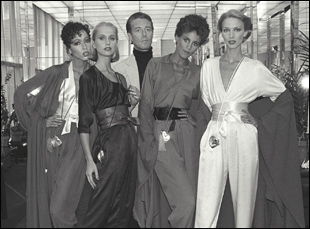

Tcheng should know, having profiled some of the biggest figures in the fashion world in films such as “Dior & I” and “Diana Vreeland: The Eye Must Travel,” which he co-directed with Lisa Immordino Vreeland and Bent-Jorgen Perlmutt, but never doing the same thing twice. And while relaying the basic biographical facts of someone with such a colorful history as Halston, a staple of Studio 54 and pioneer of fashioning runway shows as celeb-filled events akin to Hollywood premieres, might’ve been interesting enough, there is considerable art in “Halston,” which honors how he made his name while bringing up other questions around his identity – first in remaking himself from a kid from Des Moines who scaled the heights of high society in New York as a haberdasher for Bergdorf Goodman’s and then as distinctive designer, eventually in selling over all rights to his personal brand to a corporation in a bid to grow bigger and losing his personhood as Esmark, which swallowed Norton Simon, could use the moniker in whatever ways they saw fit.

To tell the story of a missing person, Tcheng naturally gravitates towards framing “Halston” in the terms of a film noir, opening with an anonymous archivist (Tavi Gevinson) working in the shadows to piece together what strands of Halston’s history remain after Esmark all but erased him from their records and gradually weaves in interviews with the likes of Joel Schumacher, a former assistant, and best friend Liza Minnelli to cut a figure for the designer as intriguing and stylish as any of his creations. Recently in Los Angeles after a festival run that began at Sundance earlier this year, Tcheng and producer Roland Ballester spoke about finding the right cinematic language to recount Halston’s story, locating all the rare footage that makes the film so revelatory and how the story grew into a larger and more compelling story about corporate culture.

Roland Ballester: When I decided that Halston was a really good film to do, you need a really good director, so I looked at some documentaries and talked to a couple people and was not really being inspired by those choices until a friend of mine suggested that you see “Dior and I.” She said you’re really going to like this film and that director. And she was right. I fell in love with it because besides being a fantastic film, it’s not what you expected. Fred’s approach, focusing on the back of the house, was really fresh and intriguing and I didn’t necessarily want the film to look like “Dior and I,” but I wanted someone who would approach the subject in a new way, so that led me to him.

Frédéric Tcheng: And I said, “Thank you, but no thank you.” [laughs] Literally, I was going to go into this meeting and say very politely that I’m not interested in doing another fashion story. I was eager to show my range and move beyond [that] and it took me a while to think of the Halston story as something bigger than the Studio 54 image, which is the one-dimensional image that people have — the guy with the sunglasses at Studio 54 with the cigarette holder. Roland [said], “There’s so much more. You need to read this book and that book,” and eventually I did. That’s really when the story came to life for me, especially the business [aspect] because I was at a point where I had been a little burned by some experiences with corporations, feeling like you’re talking to these businessmen who have your fate in their hands [when making a film] and they’re not interested in talking about making good films. Reading about Halston losing control of his company was my worst nightmare coming to life. The way that he fought and the way he built his company only to see it be taken away felt like a story that hadn’t been told and deserved to be. I saw the scope and the dynamic of something really cinematic, but it was also very personal for me, so it was something through which I could talk about many other things.

Did the detective framework immediately come to mind or did that develop over time?

Frédéric Tcheng: It was something that happened as we were developing the film. As we were gathering the initial research, it seemed like there was so much mystery around Halston, so I wanted to bring that feeling of being in the middle of an investigation out and trying to find out who Halston was. It reminded me a little bit of “Citizen Kane” — that was always a big influence on me in the way that [you could] frame the story as trying to get to know this person that is very elusive and the idea that there is a Rosebud that explains it all, and I think I was after Halston’s Rosebud.

In a way, that allowed me to create [something more] complex than just a linear story from birth to death and if I reflect on it a little bit, I wanted to do something different for my fourth film on fashion. I wanted to push the envelope a little bit, having the big canvas this time and a great story, to challenge people a little bit.

Frédéric Tcheng: What comes to mind right now is Tom Fowler, who’s the first assistant we could track down back at Bergdorf in the ‘60s and one of the interviews that I really wanted to get on camera. He told me this story over the phone of Halston coming back after a weekend in the Hamptons and telling him this appalling story of being told by the host [of a party] that he was a “faggot.” I kept on thinking about it and Tom didn’t want to be on camera at first. I had to really go and explain to him how important this story was for me because it really set me on a track where I understood where [Halston] was coming from not only when he started his own company outside of Bergdorf and outside of New York society.

The company he started was very counterculture, bohemian and very outside the rigid rules of society and [this story] helped me understand why [Halston] liked Studio 54 so much [because] if you are someone who has had the trauma of being rejected by the gatekeepers who decide who can sit at a table or not, at some point, you’re going to want to decide who gets to sit at the table. That’s what he was doing with Studio 54, and everybody wants to hear about the drugs at Studio 54, but for me that’s not the interesting part. The interesting part is about creating a new social order, and that started back in the ‘60s when he was rejected from society. For me, that opened a whole thread.

Since I imagine the fashion world is pretty insular, does access to archives or to interviews get any easier?

Frédéric Tcheng: It helps because a lot of people…I was glad even before [interviews], some of the models said, “I’m so glad you’re doing this because I can tell from “Dior and I” that you have the sensibility to go at it with empathy.” So it made people comfortable, just to see the type of films [I’ve made] because the film is a reflection of me in many ways and it’s a little bit of a calling card.

Roland Ballester: But the interviewees really did appreciate the questions and the depth of the research. Our interviews would last hours. Sometimes a four-hour interview was normal for us. In the case of one person, we had to go back twice. They went on and on in a good way.

Frédéric Tcheng: My two favorites. Elsa, we were going to go to Spain and film an interview with her, but she wouldn’t be on camera. She was like, “You can record my voice, but don’t show my face.” So it became this whole Marlene Dietrich thing and we were making plans to find a sound man there, but then I started watching this interview that had been recorded for Tiffany because she was closely associated with [the brand]. They interviewed her two months after Halston died, so she was talking about Halston throughout the entire interview and she was so raw, funny, touching and completely vulnerable, so I remember saying to Roland, “I think we have Elsa. That’s it. I don’t think we need more.” Then of course Joe Eula passed away, but we were lucky enough to find these tapes that had been recorded also around the same time that Halston had died. Right before he died and right after he died, there were two different tapes by Steven Gaines, who did the biography on Halston [“Simply Halston”] and he had access to a lot of people who died since then, people like David Mahoney and Victor Hugo. That’s extensive research [on our end], just trying to find everything we could.

Roland Ballester: Through the course of our research, we found all sorts of other things, only through tenacity. We just kept going and going and many times archival houses just would say to us, we think things are lost or we can’t find it and we pressed them. Another great source of material was the interviewees — people like Karen Bjornson gave us personal photos. They provided us with incredible things. The business people gave us these legal documents and memos that just told the whole story, particularly when we hit the conflict years, which was ’83/’84. These things read like novels, they’re so good. We didn’t take no for an answer. And there was this one tape that we kept…we have to find it, we have to find it, we have to find it and…

Frédéric Tcheng: Like NBC did a lot of filming around the China trip because they were going to do a “Halston in China” documentary, and the tapes were thought to be lost, but we kept on saying, “Can you please look here? Can you please look there?” Sometimes things are not labeled properly, even at a big place like NBC, and eventually, the treasure just appeared. It was raw footage, which was amazing for a documentary because suddenly you’re seeing probably what Halston would not have wanted you seeing.

Frédéric Tcheng: Yeah, I love the texture of VHS and for me, the film was so much about image-making and how images are constructed. We’re so used to taking them at face value now, but it’s almost like you can see how they can be manipulated more and more and it was important to deconstruct the narrative that Halston had about his life. That meant roughing up the image a little bit and rewinding it. All the glitches in the film are real. There’s no digital effects. It’s all the actual tapes and their quality and because they’ve been destroyed/recovered, they have this special texture. I remember one of the major sources was Video Fashion and they had to literally put some of the tapes in an oven and bake them to bring them back to their original quality because the material had degraded. It’s kind of amazing. It’s like a forensic examination.

“Halston” is now open in New York at the Quad Cinema and opens on June 7th in Los Angeles at the Monica Film Center, the Encino Town Center and the Pasadena Playhouse 7.