Throughout their collaboration, Daniel Geller and Dayna Goldfine have enjoyed a good creative challenge as much as they have enjoyed documenting how others have met them in such films as “Kids of Survival,” where teenagers in the South Bronx formed an art collective against all odds, and “Ballet Russes,” which preserved the history of the innovative dance troupe that sought partnerships with artists in other forms. So when their friend, the esteemed film historian David Thomson had suggested that it might be intriguing to devote an entire film to the creation of a single song, the thought leapt into the filmmakers’ minds as any good earworm does, only they would have to think about what song specifically could warrant such a treatment. Then the two remembered a concert they had seen at the Paramount Theater in Oakland.

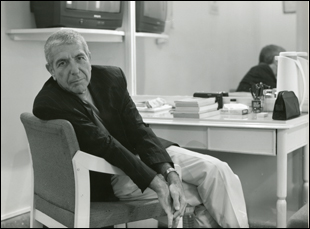

“It was a challenge but on the other hand, getting to plumb the mind of Leonard Cohen opens up one of the richest, broadest fields of inquiry that you could ever imagine,” said Geller, who could be encouraged by the fact that, as Goldfine discovered with a quick Google search, an entire book had already been written on the singer/songwriter’s anthem “Hallelujah,” in Alan Light’s “The Holy or the Broken.”

The two sought out Light as well as Cohen, who gave his consent with the provision that he wouldn’t be doing any interviews for the film shortly before his passing in 2016, and the result “Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song” is a marvelous chronicle of creativity that has as much life in it as the song itself has had, taking various forms over the course of generations after its original recording never got any traction when the album it was on, 1984’s “Various Positions,” was rejected by its label Columbia after a change in management. While it may not have had the proper opportunity to catch on with the public initially, the song never left Cohen’s mind, endlessly rewritten throughout the years and performed differently on a nightly basis when he would go on tours as he went through his own personal transformations, becoming a Zen buddhist for a spell before gravitating back to his Jewish roots and moving between different sounds, forms of artistic expression and various relationships.

However, “Hallelujah” also began to take on a life of its own away from Cohen, covered by artists such as John Cale, the late Jeff Buckley and Rufus Wainwright, whose intimate cover versions not only exemplified the depth of what its original creator tapped into while still making the song their own, but delivered it to audiences that cut across the musical spectrum, creating a fanbase for it unlike any other. For those rare few who might go into “Hallelujah” unfamiliar with the track, you’re bound to come out as fans and those who have heard it hundreds of times will undoubtedly come away with something new as those close to Cohen at the time of its writing such as journalist Ratio Sloman and producer John Lissauer speak insightfully to Cohen wrestling with its lyrics and current artists such as Glen Hansard and Brandi Carlile passionately explain their own interpretations. With the rousing doc hitting theaters this week, Geller and Goldfine spoke about how the project came to be with the co-directors delving in as deeply into a search for meaning as Cohen did and how they were able to access both the artist’s archives and the emotions that went into creating his masterwork and continue to swirl around the song to this day.

Daniel Geller: We definitely knew we were going to do one song, but the focus wasn’t as sharp in that we didn’t want to use the song as just a portrait of the songwriting process. We knew it was the window into a story about Leonard Cohen and the deep preoccupations he had about holiness and brokenness and what life has meaning and your own carnal urges versus some sense of godly perfection. Because the song is so rich and complicated, [we knew it] would give us the excuse to delve into a biography in a way through those preoccupations.

Dayna Goldfine: We didn’t know necessarily how much it was going to go into Leonard’s background, and because we chose to look at his life through the prism of “Hallelujah,” it allowed us to skip a lot of the basic details like “Leonard was born in this hospital.” So we were able to start at age thirtyish [when he] announced to the world quite surprisingly that he wasn’t just a poet and a novelist, but he was a singer/songwriter. But the way it got focused for me was about a year into the editing, I think we looked at each other and said, “This film is about ‘Hallelujah,’ but it’s really about Leonard Cohen and [we should] follow his spiritual journey because the film is about why Leonard Cohen the only person in the universe who could’ve actually written “Hallelujah.”

Were there any unexpected directions this took that you could get really excited about?

Daniel Geller: Even if it didn’t take us in a different direction, finding these archival materials just enriched everything so deeply. When Ratso [Sloman] mentioned that he had all the audio cassettes from his first interview with Leonard Cohen in the early ‘70s right up until the early 2000s — and it took us a couple years of prodding to say “we’ll pay for the digitization, but we have to use them, we have to have it” — [we knew] no one had heard these before, so you can imagine our excitement to get material like that. I don’t think it necessarily took us in any new direction in and of itself, but as we were in the edit, the movie kept declaring itself to say it’s really about this spiritual journey — it’s really about people’s journey with Leonard through that song as well — so anything that was extraneous to that began to fall away.

Dayna Goldfine: But as we were going along, as a filmmaker, especially a filmmaker like Dan and I who take years and years to make each film, you’re continuing to build your reference points to your subject, so when we started, we wouldn’t have necessarily thought or known about Rabbi Mordecai Finley, who was Leonard’s rabbi for all those years of the last 15 years of his life in Los Angeles. As we were rooting through things, up popped this article called “Being Leonard Cohen’s Rabbi” that Rabbi Finley wrote and published about six months after Leonard passed away and it was so gorgeous. We were like we need to track this guy down.

Dayna Goldfine: If you look back through all of our films, our philosophy is that we don’t tend to interview outside experts or omniscient critics. We do really try to sketch where the subject was coming from.

Daniel Geller: We did steer questions in a couple of directions. If it had been someone like [his touring companion] Sharon Robinson, of course it was “What was it like to be on the road with him? What was it like to write albums with him?” If it was someone like Ratso Sloman, it would be, interviewing Leonard over the years, “Ratso, what are the changes you saw?” For someone covering the song like Eric Church, [we’d ask] “Why were you covering the song?” but we’d always bring it over to the bigger questions of why is this song reaching so many people and the core spirituality and questioning inside this song that makes it so universal or so particular to the person that we’re interviewing, but also start hazarding guesses to the man Leonard Cohen.

Dayna Goldfine: And once we settled on this concept of let’s look at Leonard specifically through the prism of that song, it allowed us to handpick the interview subjects. Our rule of thumb was in some way, shape or form, the interviewee had to be able to either have been there like John Lissauer or Ratso when Leonard was going through “Hallelujah” or had been a part of his life in a way that they could speak very specifically and directly to his relationship to all the parts of the world and to his spiritual journey that allowed him to write “Hallelujah.”

I’ve read that you actually put the first act together for Robert Kory, Leonard Cohen’s longtime manager and the trustee of his estate, to see, which helped in convincing him to hand over the notebooks with the handwritten lyrics to the song. What was that like?

Dayna Goldfine: Really scary. [laughs] It’s not even that we necessarily put it together for Robert, but we got the first act up and running, knowing it was a rough draft, and it reflected what we were doing with the material. We decided to come down to Los Angeles and we sat in the office of Morgan Neville, an amazing documentary filmmaker who did “20 Feet from Stardom” and was kind enough to come aboard as an executive producer of this project, to show the first 30 minutes or so of the film to Robert. What Robert didn’t know before we started that little screening was that we had let our original editor go and I had taken over the editing at Dan’s urging. I never would’ve done it otherwise, and Robert sits down and says, “I want to see what this hotshot editor did.” [laughs] Dan said, “We actually have a different editor…it’s Dayna,” and I don’t know what he thought, but it was very scary to sit there with him for that 30 to 40 minutes. But at the end of it, he turned to us and said that he was impressed enough to really throw his hat into the ring in terms of what he was going to allow.

Daniel Geller: [The whole project] was very collaborative in the sense that the more we could show him what we were doing, the more trust he had in what we were shaping and the story we were trying to tell, so that’s how over time we were granted access to these polaroid selfies that Leonard took that no one had ever seen or the concert recordings towards the end of his life. We understood it would take that level of trust in each other to yield these materials, including the notebooks, the journals that have all the inchoate lyrics written out and scrawled in over the course of the years and [at the same time] we weren’t making a hagiography. It’s warts and all, but Robert wanted to make sure we weren’t doing something that was salacious or exploitative, though clearly, that’s not our nature in any of our films.

Dayna Goldfine: More than that though, it wasn’t that [Robert] was worried about the salaciousness. I think he just wanted to see how close we could come to reflecting Leonard’s spiritual journey and Leonard the real guy and when he saw the first 40 minutes, he turned to us and said, “Oh, you guys get it. I want to see where you’re going with this.”

Dayna Goldfine: The Jeff Buckley sequence was one of the ones we struggled with the most for two reasons. The Alan Light book that inspired this film is really half Jeff Buckley and half Leonard, and we told Alan early on that our film was going to tilt more towards Leonard, but we knew we had to give Jeff his due, and he’s so charismatic and his story is so gripping that to get that sequence to the point where it did justice to Jeff and to what he brought to the song, but it didn’t completely derail the film, that took quite a bit of finessing in the editing room.

It was just magnificent, and not that I would tire of the song, but something I was impressed with was how “Hallelujah” retains its power even though you have to hear it a number of times in the film. What was it like figuring out the role the actual music would have in this?

Daniel Geller: There is a very interesting thing going on in the movie that we stumbled our way into — there are 22 other Leonard Cohen songs in the movie at various points and it’s important to understand Leonard’s background because so much of it appears in different songs, you can understand his background and what he’s consumed with. Those songs are beautiful and are also interspersed so that you’re not just hearing “Hallelujah” all the way through. That’s one part of it. The other is that the “Hallelujah” versions come in and around either Leonard’s changing notions of the song as he sings it at different stages of his life or the way Brandi Carlile sings it or Eric Church and why they sing it and the why of it retunes it a bit, so in some ways, you’re hearing it anew again. When Brandi Carlile talks about how she was trying to reconcile her deep Christian faith with being a lesbian, you begin to hear these differences in her interpretation or you read into those lyrics something different.

Dayna Goldfine: And one of the reasons we felt at liberty to put these 22 other Leonard Cohen songs in the film is in the middle of the film, there’s this beautiful line where Leonard is talking to an interviewer about how he was working on his book of poems called “Book of Mercy” at the same time he was working on all the songs that were part of “Various Positions,” and he said, “Well, everyone’s work is all of a piece.” Taking that notion and building on it, we realized that if Leonard Cohen’s work is all of a piece, then it’s worth listening to these other 20 something songs because together they make up this mosaic that lets you understand and unpack “Hallelujah.”

What’s it been like getting this out into the world?

Dayna Goldfine: Super exciting. You never know when you’re finishing up a film how it’s going to be received, but we always felt that this was a film that deserved to be in theaters, so it’s been so, so, so exciting that Sony Pictures Classics picked it up and they believe so deeply in the theatrical experience. And to sit [in theaters] – last night we were at the Grammy Museum [where] we came in for the last 15 minutes [of a screening] and I happened to sit down next to this woman who was audibly emoting in all the right ways. It was the most gratifying thing ever. It’s why we do these things.

“Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song” opens on July 1st in New York at Film Forum and Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal before expanding nationally on July 8th.