As David Redmon had learned throughout the making of “Kim’s Video” over the better part of a decade, it was best to let things play out when he presented the film for the first time to a few of its executive producers and among their notes was tossing out the score.

“They hated it. They said, ‘You cannot put this trash in the movie,” recalled Redmon, who sat quietly as plans were being made to take the music out entirely despite how fundamentally intertwined Enrico Tilotta’s music had become with the film when the composer was one of the first people the filmmaker met in Salemi, Italy when he began his quest for the fabled inventory of the beloved video store Kim’s that had been relocated there from New York. “I just sat there for three minutes in pure silence. But we never heard a word from them again, so the music stayed and what we would like to do is make a vinyl now.”

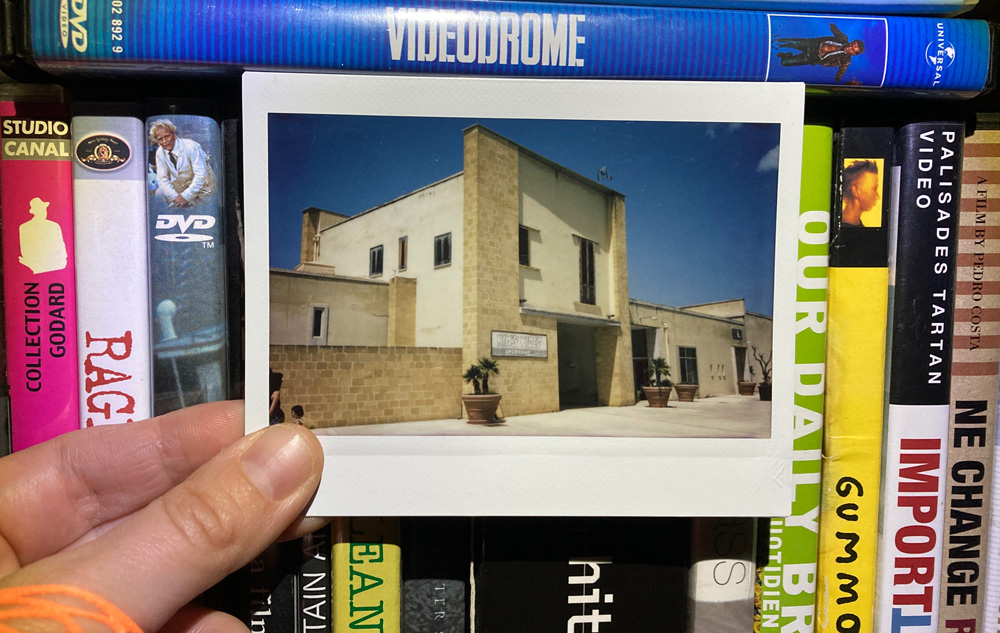

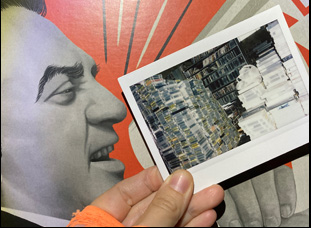

Putting things on the permanent record was always the goal of Redmon and his partner Ashley Sabin when telling the story of Kim’s, which not only involves the strange disappearance of a 50,000-strong collection of VHS tapes and DVDs that nourished film students both at nearby NYU and those who couldn’t afford its tuition but the transient nature of the city itself where the rebellious spirit of the mom-and-pop shop started by Youngman Kim in the East Village now seems to be the relic of a bygone era. When Kim’s clerks were known to bootleg all that wasn’t legally available due to arcane rights issues and a lack of motivation on the part of American distributors to pick up foreign titles, it is fitting that Redmon and Sabin couldn’t always play by the rules in order to do justice to their subject, with the former seizing upon a tip that Kim had put his collection in the care of the town of Salemi where community leaders had intended to build a cultural center around the film collection, with the promise that anyone with a Kim’s membership card could continue to check out films if they made the trek from America.

Having done just that, Redmon was frustrated to learn that not only the collection was inaccessible to him, but even to the townspeople of Salemi, with Tilotta living above where the collection was rumored to be housed and less forthcoming about it than his musical ambitions. The fact that the two would bond over movies, eventually coming to collaborate on one, becomes a lovely reflection on the kind of community drawn together by art and the obsession it breeds as Redmon constantly can be heard comparing his quest to uncover what happened with the collection to films he remains haunted by, finding himself at the center of a bewildering mystery where local officials may not be able to be trusted but he can follow his own intuition from the films he once borrowed and hopes to recover.

It may be a spoiler to say that the Kim’s Video collection is now back in New York at the Alamo Drafthouse in Lower Manhattan, ready to accommodate anyone who feels like browsing its aisles after Redmon and Sabin’s film opens in New York this week. (Likewise, cinephiles in Los Angeles can immediately walk directly from the movie theater inside Vidiots to rent from the Eagle Rock store’s sizable collection.) However, that end result becomes just one accomplishment of many for Redmon and Sabin, who miraculously transport audiences to the video store in its heyday, conjuring the feeling of discovery inherent in any visit when it was a portal to different worlds as former clerks and customers attest and pulling a film off the shelf meant spending time in the company of fascinating and enigmatic characters like the ones Redmon engages with such as Kim, an inadvertent savior of cinema who came by preservation after starting out in dry cleaning, and wily ex-mayor Vittorio Sgarbi, whose intentions for welcoming the collection may be suspect.

On the eve of the film’s release across the country after first premiering at Sundance last year where Redmon’s obsession proved instantly infectious, the co-director spoke about how “Kim’s Video” became a compulsion, how a leading role in it became inevitable and what it’s like after years of making documentaries to become active in shaping reality after long observing it.

I grew up in rural Texas, right? And sometimes my parents put me in Bible school because they had to work full time and they had no childcare. And in that Bible school, they taught me predestination, so, as you mentioned, all this was already written. It was just meant to be. And what you’re talking about is, there is no rational explanation of how this came together. It was just both out of curiosity and a will to understand what happened to that collection called Kim’s Video on St. Marks Street. Ashley encouraged me to go rent a movie, and she said, “Just pull out your old Kim’s Video membership card, go to Salemi, rent a movie, and find out what happened to that collection.” At worst, you have this story of “Wow, I got to see the collection, and at best, maybe we make a documentary about it.”

What was the nature of you collaboration with Ashley on this? It seems like it could work really well when you were deeply in this experience and she could see it from the outside?

Well, I wish she was here because she would tell you that she often keeps me in check, and she does not give me permission to do things that I would like to do, so we have this symbiotic/push-and-pull relationship. Mostly it’s me pushing and it’s her pulling me back and in this situation, she wasn’t able to go to Salemi with me, except twice [towards] the end of the movie, and I think once again after we finished the movie, so what I would do is record as much as I could, and come back home and give her the footage, and she would organize it and try to do a rough edit.

Did you know what your own presence in the film would be?

I didn’t really want to be a part of the movie and I didn’t want my voice in the movie at all. I hate my voice. But what happened is we kept making these rough cuts and showing to people and they were so confused about what happened, they told me, “You’re the protagonist. You’re the one pushing this entire movie and you have to be at the foreground of this story.” So I reluctantly agreed and this is eventually how I entered the story. But I don’t think you ever see me in the collection. You hear my voice and you see my hands repeatedly, and that decision came about in year five — it took us six to finish the movie, and once we made the decision to have me as the narrator and the person trying to track down these people and reconstruct how this story happened, the threads of the story came together.

It’s really great how you’re able to engage this broader idea of cinephilia when you end up comparing what unfolds to experiences you’ve had watching other movies. How did that take shape?

In year three, we decided to try to include different clips from various movies in the collection and we tried to go through the movies that we had rented and in different orders, [like] from the earliest to the latest. The reasoning at that time was that those movies had an influence on us, but then we had the idea to pull out the movies that imitated different scenes in the movie and this is why you have such a pastiche. The movie doesn’t have a singular voice. It has multiple voices, and by having multiple voices, it has a singular vision, if that makes sense.

Some of the criticism of the movie is that it doesn’t know what it wants to be, but in fact, it’s the opposite. This movie knows exactly what it wants to be because it told us this is what it wants to be and the entire movie imitates Kim’s Video. Kim’s Video was so diverse. It had movies from all over the world and it was so colorful and so alive, so we wanted to pay homage to Kim’s Video and try to construct a movie in a similar fashion with the same amount of joy that the collection embodied.

One of the many regrets we have is that we had to cut out a lot of movies from all around the world — South America, East Asian countries, the Middle East, and Australia. The lawyer said, “You can’t have these clips in and I’m not going to get into why.” So at the last minute, we had to pull out a lot of those movies and substitute others.

It’s so complicated and I’m not even sure I still understand it, but what I think the lawyers were trying to tell me is that anytime we source a clip, it has to be available online and we’re not the ones who can put that movie online and then source it. Second, we have to source the clip from the United States or the UK, and I never really understood why, nor did I understand how is anyone ever going to find out where they were sourced. But this is the reasoning that went behind us having to remove clips from different companies. For example, we uploaded some clips from Bong Joon-ho, but the only ones we could find [online] were subtitled in English and for the lawyers, this subtitle originated from a company in South Korea, so they said, “You can’t put that in there. That clip came from South Korea. It has to come from America” and that’s what we were up against. We didn’t want anyone to be sued, so we did everything they said to do and we had to renarrate the movie and had to have more of my voice, which is another regret, but it’s 110% in the clear now.

It certainly came out well, and you alluded to something that I greatly enjoyed when describing a criticism of the film, which is how you quickly discard the movie I think most expect it to be pretty quickly as some trip down memory lane with customers and clerks at Kim’s and it becomes something more adventurous with those voices urging you on. Did you know at the interview stage that might be how this might end up?

You said it better than what we could say because we’re movie lovers. I don’t have a very good memory and I can’t recall a lot of movies, or even the directors, but one thing that we do recall is the structure of stories and so many of these stories about an event or an institution that once existed are told in past tense through talking heads. There’s nothing wrong with talking heads who were there and can speak about the event in the past, and there’s a lot of archive footage in the past, but one challenge we had is how can we move this forward, make it part of the present, and give energy and momentum to the story.

Part of my response now goes back to the question you asked about deciding to include myself in pursuit of Mr. Kim and trying to find out what happened to the video collection, because it gave [the story] a present tense kind of energy and it set up the question of what’s going to happen next? If [I’m] entering this dangerous situation, how’s he going to get out of it? So it hooked the audience in terms of wanting to know, will this collection leave [Salemi]? If not, how is David going to get out of the story? And the only way to get out of the story was to take the collection to get it out. So the mission to get the collection out superseded the telling of the story, and at some point, I said, I’m not making a movie anymore. We’re just going to get the collection out and out of will power, we kept documenting ourselves trying to get the collection out, and we had just enough footage to put it into the movie to show that we were also the active protagonist along with Tim League and Mr. Kim at the end.

This must be a real trip for you with the background in documentaries that you have seeing how you’ve actually made a movie that has changed reality – the Kim’s collection is now housed at the Drafthouse in New York. And I’ve heard that you wanted to make a fiction film about the making of this. What’s it like blurring reality and fiction in this way?

This movie did tell itself. I mean, and even though I told you at the beginning, I went to Bible school and all this, I’m a very secular person. I’m an empiricist. So when I entered the collection [in Salemi], the movies spoke to me and they said, “We want to go home. We want to get out.” So at that point, the movie began to write itself and all I had to do was listen. And now here we are writing this fiction script and we were done with it about two months ago, but yet it continues to write itself. We continuously hear the voices speaking to us and saying, “No, this is what you need to do. This is how you need to write it. This is how it happened. Let’s do it this way.” All we have to do is wake up and then write that down and now we have to find [the money] to go out and make this movie and I’m not even sure what this movie is going to be. It’s not fiction. It’s not nonfiction. It’s going to be a hallucination is what it’s going to be.

“Kim’s Video” opens on April 5th in New York at the Quad Cinema and Los Angeles at the Alamo Drafthouse DTLA and Vidiots. It will expand on April 12th to the Alamo Drafthouse Lower Manhattan and the Film Noir Cinema in Brooklyn, the Lumiere Cinema at the Music Hall in Los Angeles, the Digital Gym Cinema in San Diego, the Grand Illusion Cinema in Seattle, the Gateway Film Center in Columbus, Ohio, and the Kiggins Theater in Vancouver, Washington.