If Darius Clark Monroe had his way, you probably wouldn’t be able to read a credits list before seeing “Evolution of a Criminal” to know that he directed it. In fact, given the vague, one-sentence synopsis that graced the film’s SXSW program, he’d probably prefer it if you didn’t know anything about the film at all. So to respect Monroe’s wishes while giving his film the ample respect it deserves, it can be said that “Evolution of a Criminal” is an exceptional film, taking a personal story about becoming entangled in the American legal system and creating an undeniably potent portrait of the vicious cycle it has created for low income families, particularly African-American men, as well as a moving testament to the power of transformation.

If that’s all you know before going into “Evolution of a Crminal,” you’ll be better for it, yet what Monroe accomplishes is worthy of far more discussion, appearing almost amateurish at first until the absence of professional polish draws one in closer as an intimate autobiography. For its first 15 minutes, Monroe quite literally places you in his seat, with family members ranging from his Aunt Carlos and Uncle Cory speaking directly to the person behind the camera to describe how the fallout out from “your” actions fractured his immediate circle to his mom Sigrid, tearfully looking dead center to say, “I’m going to tell you what really happened.” The effect is immersive and unnerving, nearly in the same way that Jonathan Caouette’s “Tarnation” was a decade ago.

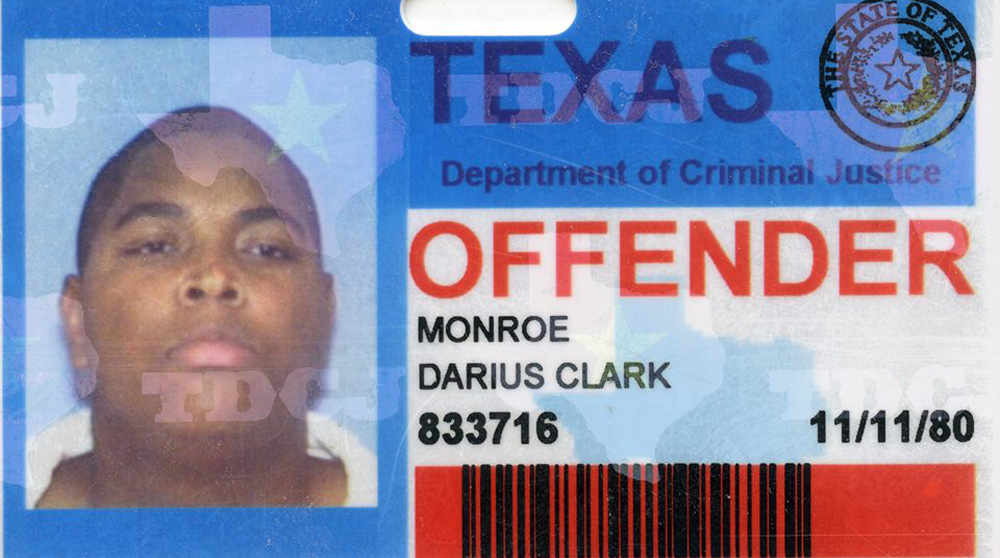

Yet while Caouette toyed with iMovie effects to get into the head of his schizophrenic mother, Monroe’s investigation into his past is so earnest and straightforward that it positions his plight as something that isn’t unique, with the director eventually appearing on camera himself to explain the moment when he was “acutely aware the world was not as I saw it and the burden my parents had was trickling down to me.” Shown in old pictures as a bright, smiling child, Monroe recalls how his family lived in poverty, unaware until the age of 14 that others had it better than he did. A member of the student council and the kind of kid fathers trusted their daughters, he did what any dutiful son would do by trying to help his mother make ends meet after a devastating robbery, only he decided to turn to thievery himself.

An escalation of Monroe’s crimes eventually land him in prison, a period of time that he obviously survived with some perspective since it’s unfolding through his lens before your very eyes. But Monroe is less interested in his perspective than those whose lives he’s affected, visiting victims of his robberies and even the skeptical former district attorney who prosecuted his case. The different viewpoints give the film a jigsaw puzzle quality, the pieces of testimony gradually adding up to something that Monroe can finally understand for himself with all the jagged edges of both the hard truths of what he hears as well as his relative inexperience as a filmmaker fully on display.

Some of the film’s recreations of Monroe’s crimes feel a bit like padding and the use of visibly cheap camera equipment in the early interviews with Monroe’s family give “Evolution of a Criminal” a fuzzy, oddly nostalgic feel that seems at odds with its content. However, the film’s raw power prevails as Monroe’s story takes shape from the multitude of interviews he collects, all illuminated by the filmmaker’s intrinsic knowledge that what happened to him speaks for so many more. Subject to the whims of a legal system that classifies his teen transgressions as those of an adult, Monroe deftly illustrates how much luck rather than reason factors into sentencing that all but erase his ability to be an active member of society later in life and while he never directly addresses his race as a factor, the fact that part of his prison sentence in Texas involved picking cotton says all that needs to be said about the notion that America’s penal system is simply slavery under a different name.

“Evolution of a Criminal” would make an ideal companion piece with Andrew Jarecki’s “The House I Live In,” which used the ill-conceived war on drugs to take a broad view of the issues of class and race that have imprisoned entire generations well before they ever reach jail. Still, the film can certainly stand alone as well as a truly unique first person account of a situation that affects millions but is all too rarely spoken about, much less with such insight, and while this is only the start for Darius Clark Monroe as a filmmaker, it’s the fact that he’s come so far as a person that makes “Evolution of a Criminal” something special.

“Evolution of a Criminal” does not yet have U.S. distribution. It will play at the Dallas Film Festival on April 4th and 5th at the Angelika Film Center at 7:15 pm and 9:30 pm, respectively.

Comments 2