“Dallas, 2019” shows an unusual level of perception as you take a seat in a Texas courtroom and the camera refuses to be locked into a stationary position, perhaps constrained to a particular location in the gallery, but refusing to take a direct approach. Steadfast rather than jittery, the lens will tilt downward at a curve or pan to the side as testimony is given in a civil suit against BlueStar Recycling, a company that may have been responsible for causing more environmental damage to the community than improving it with its application of asphalt, and in looking around rather than straight ahead, one can take in the shape of what’s going on in a way that would surely elude some dry, fixed perspective.

It’s an instinct that serves director Darius Clark Monroe well over the course of the five-episode miniseries about the inner workings of Dallas or more specifically South Dallas, where city resources have a way of running out before finding their way to more predominantly Black and brown communities. However rather than bring shame to a system that doesn’t work as it should, the director keenly observes why that’s the case, building a brilliant structure for each episode around three residents at various levels of society, from government officials to those whose lives have been directly affected by public policy, whose goals may align but may not see eye-to-eye from their various vantage points. When conversations about the future can be futile when people are hardened with the knowledge of how things always have been, the ability to see the situation from multiple angles undoes a logjam as conversations that take place within bureaucratic structures about hypotheticals are put into sharp relief by the people that Monroe follows on the ground going about their daily lives.

Starting out at a county fair with its sprawl of various attractions, “Dallas, 2019” envisions the city in similarly adventurous terms as it peeks in on a football game at South Oak Cliff High School or checks into the county health and human services department, finding the machinery of it fascinating and while Monroe and crew create individual profiles of the people they engage, a grander picture emerges of the institutions that have become larger and less accommodating of the present reality than when they were first designed. Remarkably, the series becomes something equally monumental as its subject, only far more accepting of the human element at play and with “Dallas, 2019” premiering this weekend as a two-night event on PBS’ Independent Lens before being made available to stream online, Monroe spoke about how he had to broaden his own outlook on what a project like this could entail in capturing how a society functions, looking for connections between people of different professional and cultural backgrounds and tying a moment in time when he filmed in 2019 to a larger historical arc.

At the end of 2018, Noland Walker at ITVS just sent me a text and they were working on a project in Dallas that was focused on criminal justice, but they were stuck. They wanted to make this documentary into a larger series, and they weren’t necessarily sure how to shift from a feature into an episodic series. So I flew out to L.A., and once they told me about what was happening in Dallas, and being from Houston, I was definitely intrigued. I pitched them with the idea of not just focusing on the criminal justice system but expanding that scope and looking at the city through the lens of public representatives and the folks on the front lines. I said, “We should not just talk to the judges and the district attorney, but to the superintendent, that we the city manager, the medical examiner, and we should get a wider understanding of how does the city function, who are in these roles, and how does the city impact our lives? And they were open to it.

There’s a fascinating conceit for each episode, which is that there are three people whose lives intersect and ultimately a main subject emerges. At what point did you realize that could be an effective structure?

That was a challenge. I’d never done a doc series, so the structure of this is something that I’m really, really, really proud of because my editor, Doug Lenox, who I’ve worked with for 12-plus years and I were committed to not just doing something for the community, but something that also felt artistic and honest and grounded. We knew we wanted to have these episodic motifs, but we didn’t know by filming who was going to be in the episode with one another. We had an idea that “Oh, these two people seem like they would make sense in the same episode,” but it wasn’t until we got into the edit — and we were in the edit for five years — that we came up with this structure that it seemed to work best. [It was not to] have five or six people in a 45- 50-minute episode, but to let three people speak and breathe. I also loved the experience of going to a new episode and being introduced to even more different people in the city, so we’re not just following everyone for five episodes, but every episode you’re introduced to new communities and new perspectives. Having three voices, so there’s this triangular motif really worked.

It really does. And you’re able to show institutions through the people, but I imagine access might’ve been limited to such places as courtrooms and hospitals, so how did you realize there was a way to tell that story?

This was always an exploration through the lens of the people, so even though we knew we were tackling these huge institutions, you can’t just tackle Dallas health care [for example]. That’s such a massive thing. But to look at health and at HIV rates through the lives of the director of Health and Human Services or someone like Zimora [Evans], who works at Abounding Prosperity, it feels more intimate. And what’s beautiful is that a lot of the individuals who are in the series are city leaders who gave us incredible access. In episode two, we’re filming with the sheriff [Marion Brown], but the sheriff also says, “Hey, separate from me, you can come and shoot and film inside the jail. There’s something you want to see in intake.”

The whole purpose of this was not to catch people in trouble or do an expose, but we really wanted to observe and to bear witness and to show the minutiae, granular parts of the day-to-day and people may know about getting in trouble and getting bonded out [of a prison], but have you ever been through intake? Have you ever sat down and gone through the paperwork of having to bail somebody out? These experiences are pervasive throughout Dallas and throughout the country, but a lot of times we miss these moments, and the series really gave us the opportunity to look at these different scenarios through the lives of people, but also have the time and space to focus on all these moments that really speak to larger issues in our society.

There are real cinematic flourishes in the camerawork, which makes it distinctive for this kind of nonfiction verite. What was it like for you and Christine Ng to figure out?

Christine Ng is phenomenal. It started with a meeting at the Dallas Aquarium. I’m not really a director who uses references or likes to watch other things [for reference]. I really try to work hard to come up with something original, and my brother, who’s a photographer and a cinematographer, told us to go to the aquarium and check it out. So Christine and I were walking through, looking at the different levels of glass and distortions as we looked at the different fish and wildlife, and we were saying it’s just fascinating how you can experience something that you’re very familiar with in a different way through the prism of glass. So the language of the series came from the conversation that day and we really wanted to do something that was familiar but also felt strange, like out of body. The style came from us just playing with the lens, and there are moments where you may watch something and see different variations of a person’s face, like in episode three with Zamora at the very end before a performance. Even with Sherriff [Marion] Brown, there’s just moments where we’re introducing glass and prisms as a way to focus, but also to highlight how uncomfortable and strange this situation may be.

You bring a real artistry to incorporating history into this in a way where it doesn’t feel like looking back, but there are these vignettes like when you go to Dealey Plaza and it feels like the Kennedy assassination still echoes after all these years when you bring it into the sound mix. What was that like to put together?

When watching documentaries, we didn’t want this to feel like an afterschool special or an assignment, even though this is informational and you can educate yourself from this. Obviously, that footage from Dealey Plaza of the JFK assassination has been shown so many times, but I had never seen the actual memorial until I went to Dallas for the series. I didn’t know that there was this massive structure in honor of that horrible day, so there was something about juxtaposing the present day with the past, and not even just connecting it with the history of Dallas, but connecting it through the lives of the people who are in the series.

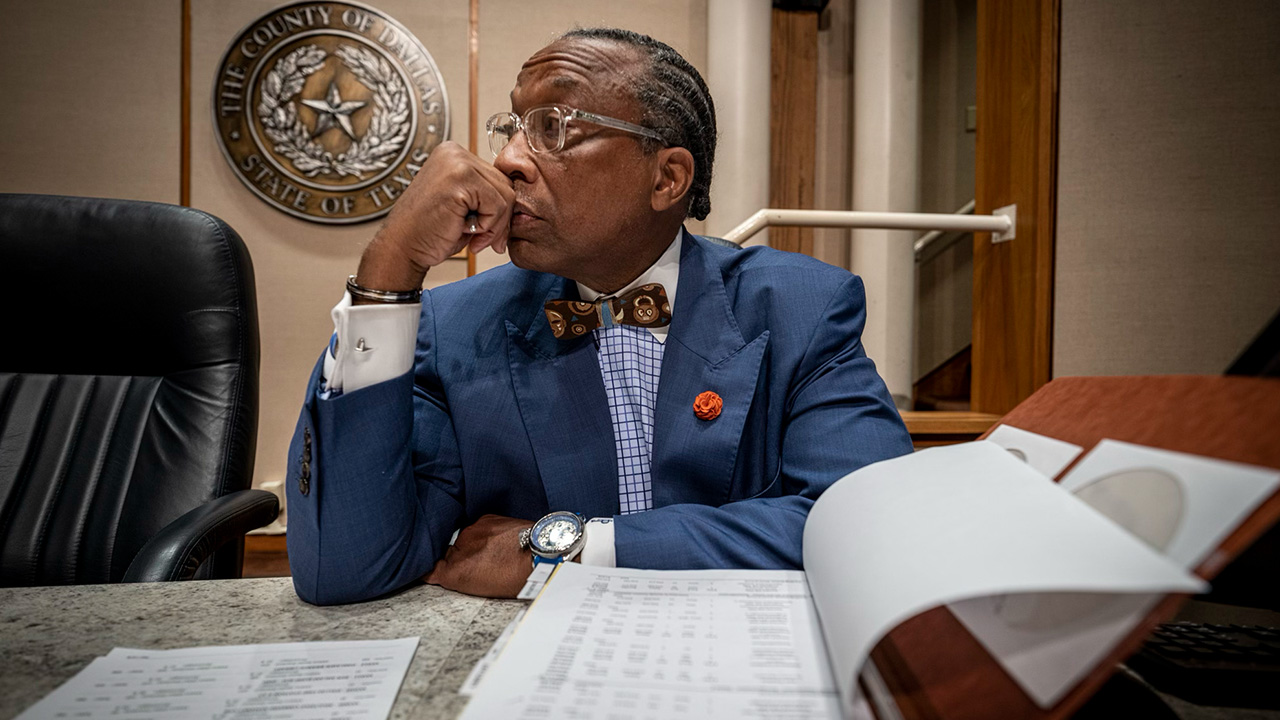

So that JFK audio is juxtaposed or wedged between John Wiley Price, who’s talking about the history of the city and the county, and Dr. Wong, who’s going to get another meeting that’s probably going to be stressful about just being on the front lines, and there’s something about the representation of this idea that sometimes we dismiss the weight that these individuals carry and that some people have literally lost their lives being on the front lines representing the public in this country [such as] the president of the United States. There’s [a scene in] episode three where John Wiley Price is speaking to all of these issues, almost as if like a movie he’s seen before and we’re seeing all of these beautiful black-and-white and color archival [footage] and we were using this material to just reinforce the things that are weighing on the individuals who are in the series, and by extension, on all of us.

A lot of things that the series is trying to show historically has happened before. These things are not new, and the will and the desire to defeat these systemic [issues] and to better undergird these institutions has always been there, but people doing that work have had a hard time due to some of the pushback, and sometimes just the political nature of our country.

With this many stories, were there connections that you could only make once you got back to the edit are you were seeing how these storylines that were in parallel with one another?

Yeah, we shot this in 45 days, almost like a feature film. We didn’t want to do a series where you came to Dallas, you get a little bit, you leave, and you come back because we felt like people would change a lot. We wanted to make everything consistent and be in this bubble and during that time, I kept assuming, “Oh, we’re filming with the city manager, so maybe in this episode, this other individual will work [as a part of an episode].” But that didn’t go really well. It was very difficult to figure out in production how this is going is work. I knew we had the scenes and the people, but until we got into the edit and really comb through the observational footage, but more importantly, the interviews themselves, we started to see a lot of overlapping themes.

It took us many years to really land on this final structure because other people were in different episodes. Some people were split up into multiple episodes. But we realized, “You know what? Three works best, and then if possible, the full experience of these three should be represented in a single episode. No one should drift to another episode unless they’re like a background participant.” So for instance, you see Sheriff Brown in episode three, but she’s not fully realized in the way that she is in episode two. She’s s a background addition to what’s happening at the jail with the commissioner, but it’s her main thing. And that really is what helped us. We started to see that people who had different lives and completely different realities had similar interior thoughts and similar struggles, concerns, and desires, so that really was powerful.

What was it like to actually take this to screen in Dallas?

It was incredible. We had a screening on November 22nd, almost on the anniversary of Kennedy’s assassination at the Dallas Museum of Art, and I was nervous to present this to the participants who were city officials because of their roles. I wanted the people who gave us their time and energy to actually enjoy the experience of watching this. And the Dallas community showed us so much love and so much care. We screened three episodes and still had time to talk for another hour, even after the Q&A, so for people to sit down for about four hours to talk about this, it just means a lot to me and the whole entire team who produced this. A lot of intentionality, art, and tears of sweat went to this and it’s not something that should be dismissed.

“Dallas, 2019” will air on PBS as part of Independent Lens as a two-night event on January 3rd and 4th. It will be available thereafter to stream via PBS.