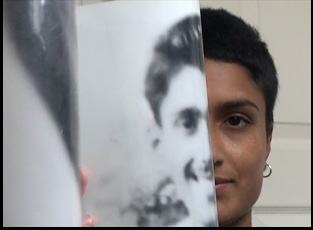

“Everyone’s told me you have my smile. You have to be wary about it – it might get you into trouble,” Chloe Abrahams can recall her mother Rozana telling her in “The Taste of Mango,” knowing that behind the smile lies a lot of pain. Abrahams could only guess how much based on what had been shared with her over the years as Rozana rarely had occasion to talk about her Nana Jean when the two were estranged from one another. An opportunity to reconnect was only granted by Abrahams’ burgeoning career as a filmmaker, using the camera as an invitation to discuss what had been previously unmentionable in the family regarding Jean’s second husband, long gone from the picture, but nonetheless looming large over their lives to this day when Jean feigned ignorance about his behavior around her daughter.

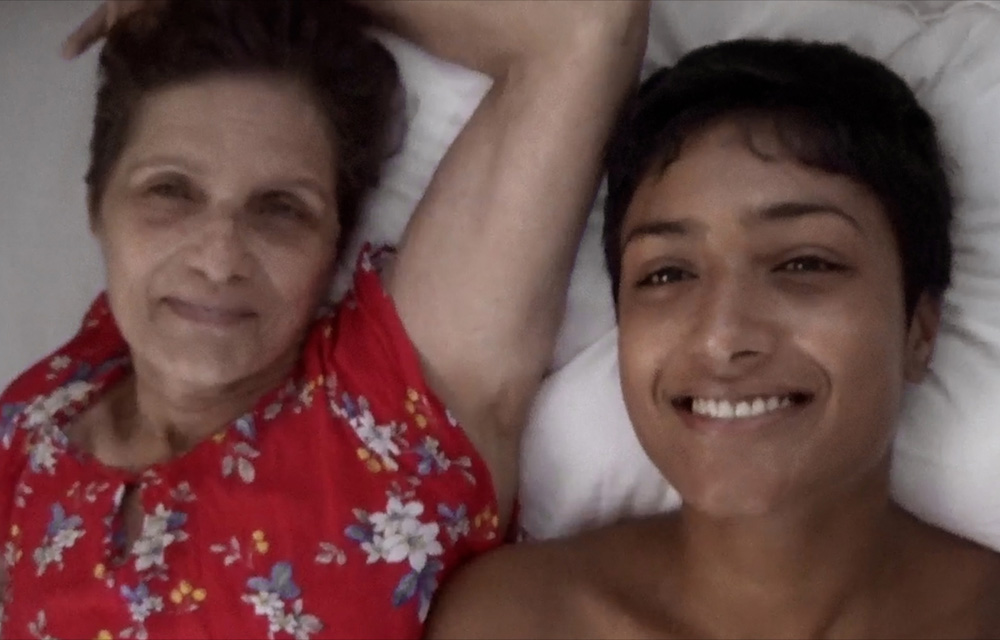

Taking something ugly and turning it into something beautiful is at the core of Abrahams’ glorious debut feature, captured largely with a consumer-grade camera where the digital grain takes on a certain tactility as the director cuts through it to find clarity. Her mother Rozana is never less than luminous and emanates a warmth that is reflected in a sharp wit and the occasional crooning of country music, but it remains a tall order to break the ice that’s developed between herself and Jean and by zooming in on the initially awkward time spent together, Abrahams is able to present a remarkable view that stretches across generations of trauma that’s been passed down that none of the women may bear direct responsibility for, but have let it fester when letting it go without acknowledgement.

Abrahams may end up capturing a reckoning, but nothing feels forced and whatever distance may exist between Jean and Rozana is not placed between them and the audience as the filmmaker tenderly offers a voiceover of the questions racing through her head as if she’s leaning in to whisper into your ear. While there’s a lot to process, the director’s sensitivity to the situation affords access for both her subjects and outside observers to emotions that might seem intimidatingly out of reach without such a gentle presentation, with the past feeling both immoveable and potentially insurmountable, but also gradually lost in the sea of time as life moves on around them and Abrahams is so deeply attuned to its natural rhythms. The film has surely rattled around in the heads of anyone that’s seen it on the festival circuit since its debut last year at True/False, including its director who could see it anew as she became a mother herself in that time and with “The Taste of Mango” now rolling out theatrically in the U.S. and U.K., Abrahams graciously took the time to talk about how films have helped bring her family closer together, making practical aesthetic choices that have paid off creatively and broadening the story by putting more and more herself into the picture.

It’s been a really long journey. I had the idea for the film around 2018. My other grandmother had just passed, so Nana was my only living grandparent left. I didn’t have a relationship with her and I could feel the kind of growing resentment from my mom. I had just come out of art school, making very personal work and I could feel that it was helping me and my family members just within our small circle to talk more openly about things. I could feel that it was helping me almost bring something out of myself so that it could be tangible to work through. And both with my work and with my connections with people, I think I just have to go very deep or nothing, so it just felt like making the film was the only way I knew how to work through these things.

I thought [a film] would be more about reconnecting with my grandma, so I started off trying to make something around that. Then I went to spend a bit of time with her in Sri Lanka and when I came back, I left feeling really disappointed and disheartened, like she was maybe never, going to see things the way that I wanted her to. Then I was so angry with men in general and that kind of anger was really bubbling inside me. It felt like, “Okay, there’s something more than what I thought would be reconnecting and it slowly evolved over the next few years.

You mentioned making personal work before this and I remember that there was a previous work about your mother and her sister. Could that be a bedrock for figuring out how to approach something like this?

It definitely did, yeah. The piece that I made for my graduate show was a two-channel installation and my mom and her sister only met when they were 18 and 24. My mom’s older sister had been abandoned by their mom and and was never told that she had other family members, so my mom overheard whispers and tracked her down. They eventually met and now they’re very close — they live five minutes away from each other — but they had never spoken about the past. It was something that they just pushed to the side and pretended like it never happened, so I asked if they would be willing to talk about it. They were very up for it and I just recorded audio of the conversation and then turned that into a script. My sister and I spent the day performing as them and then the final piece is between their conversations and our own about the family secrets. We showed that within our family and I wasn’t expecting very much. There are funny moments in there and it was a bit like me and my sister playing, so I thought that maybe they would just ignore the heavy things and laugh about it. But it ended up opening up a lot of conversations within my family about what had happened, so I was really encouraged that maybe continuing to work on things might open up some more room for conversation.

The idea of a two-channel installation to convey that seems indicative of a playfulness in terms of format and an embrace of what was available to you as far as equipment that’s in “The Taste of Mango” when you’re able to really use the texture of what you can pick up on a consumer-grade Handicam to your advantage. What was it like to get the right feel for this?

I was so resistant to the camcorder at first. I thought that nobody would take me seriously, and so many funding applications that I got, I would receive actual feedback saying, “We wish this was filmed better.” So I thought the camcorder aesthetic was maybe not translating in the fundraising materials and I was a bit ashamed of it at first. But once I embraced it, it was so clear that this was the only way to tell the story authentically because we’re not setting up shots. It was just getting this camcorder out when something’s happening and it allowed for these intimate conversations. I had filmed with my mom with a big camera earlier, and she was so cold and awkward and nervous, [which] is just so far from who she is in real life, so working with the camcorder felt like it was the only way for me to translate my mom’s character onto screen.

I realized as the film progresses, there are moments where you aren’t behind the camera and you have another cinematographer there for some emotional conversations. Was it interesting to actually bring someone else into the room down the stretch?

The two other people who shot were both close friends, so it felt also very intimate in a way, and filming with my grandma, especially that one very difficult conversation that we have, it actually just felt helpful to have somebody else present because I couldn’t shoot with my grandma in the same way that I could with my mom. There was a distance and there needed to be more distance than with my mom. I tried with the camcorder to open up with my grandma, but I think I couldn’t go there. It was harder for me to have a natural, intimate conversation with her. It needed to be more set up in a way where it was like, “We’re going to sit down and have this conversation now.” So everything was shot in the way that it needed to be for all of us to open up in the right way.

I think for my mom, it naturally became more about her. especially as I shot a lot with my grandma when she came to visit, but then after she left, I moved in with my mom for a while, so we were just together and filming things at home. It felt more natural because I realized that I was trying to understand more about the impact that [these events] had on her. I was very resistant to put myself in it too much, and I think a lot of personal filmmakers say the same thing that they started off thinking that it wouldn’t really be about them and eventually it’s like, “Oh, it’s all about you.” But of course, you’re drawn to these things for a reason and as far as including my own story, I knew that I didn’t want to do that until I had the chance to talk to my mom myself.

I didn’t want the film to be why I was doing that, so that last moment [in the film] only came in in the last two weeks of editing. We were at the Jacob Burns editing residency and I went into the recording studio on the last day and that [memory] came out as I spoke. I realized that I was finally ready to tell her and that moment of voiceover was the only take I did of that part. It actually just fit into the cut without re-editing and then I realized all of these things had subconsciously already been there. There were a lot of echoes that happened with the bathtub [scene] and lots and lots of things that I had clearly already subconsciously been thinking about.

In a broad sense, did you actually know what you would do with the voiceover before getting a lot of the footage or would you find yourself responding to it? It’s quite lyrical.

The imagery was definitely secondary to the writing and the writing went through so many different iterations. A lot of the bits of voiceover that come in I had written over the last few years, like little notes on my iPhone. I keep so many notes like shopping lists or dreams or draft text messages or little observations and much of [the voiceover] came from those and were rewritten, so in a way, they were almost like mini scenes that had been shot and I thought about them in that way, not trying to use the voiceover as something informational, but as its own little texture of the film. Then I would work through a process of seeing what imagery worked and often the imagery would do completely different things when you change it, even with the same voiceover.

You also have this really vibrant and soulful score, which I only later learned was actually composed by your cousin Suren Seneviratne. What was it like to bring him aboard?

I love the score so much. And there was not even a thought of anyone else who I would work with, but this is also his first film score. I was using some of his previous music as temporary score, so there was nobody really in mind who else could do it and I approached him. He’s my mom’s sister’s son, so Nana is both of our grandma, but he didn’t really know anything about the story and I just threw him into it and showed him a rough cut. He had to take a while to figure out what he was going to do, but it was a really wonderful process. What I really loved was that it wasn’t scored after the fact. We worked with the original score for three or four months of editing, so it was really part of the process and we just wanted to create something that would counteract what might be heavy. Alot of the temporary score that I was using underscored the feelings rather than playing with what you might feel, so it was really special to work with him [beyond] keeping it within the family as well.

From what I understand, this has been a very momentous time in your life since the premiere at True/False last year as you’ve become a mother yourself and now have this film in the world. What’s it all been like?

It’s been really, really incredible. We’ve had two waves in a way — the first wave of the festivals and my mom came around with me on tour, and then I got pregnant. Six months ago, I had a baby and now we’re releasing the film in the U.K. and the U.S. and now my baby’s coming along with me, so it means a whole load of new things now that I’ve had a baby. I haven’t actually watched it since I gave birth, but just when I think about the film, I was thinking so much about how I wanted to be a parent and things that I didn’t even consider [come to light], like the way I was shooting, the kind of closeups of my mom’s eyes, of her doing her makeup, of her in the bath, now I look at my son looking at me in the same way and focusing on little details of my face. It feels so special that feeling is also in the film. and that he is looking at me in that way.

And it’s always so touching, walking into a room full of people who have just seen it, [where] you can feel the emotion in the room. It’s also been very special when people are able to meet my mom afterwards and talk to her. She’s been getting a lot out of this process of sharing the film and speaking with audience members. because the main reason she wanted to do it was because she knew that her story had the power to help other people and she can see that it’s doing that, so it feels really, really incredible to witness her experiencing that.

“The Taste of Mango” opens in New York on December 4th at the DCTV Firehouse and Los Angeles on December 6th at the Laemmle NoHo 7. It will screen at the Austin Film Society on January 2nd.