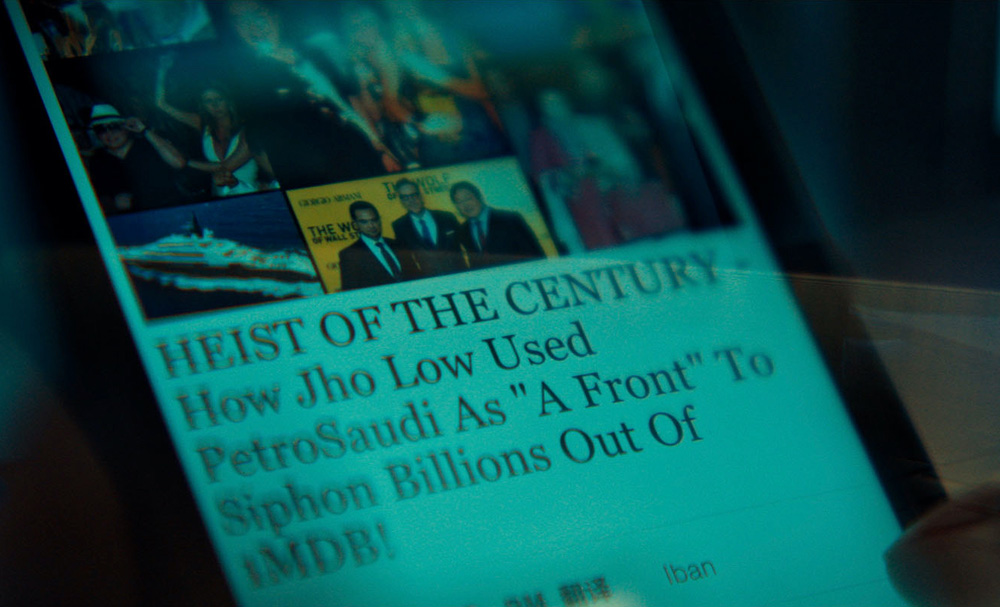

Jho Low certainly isn’t the first with dreams of making movies, only to be undone by them, but few have experienced it on the scale he has. With aspirations of partying alongside Paris Hilton and Leonardo DiCaprio, the Malaysian businessman started out his bid to make it into Hollywood by throwing one soirée after another, paying bold-faced names to show up to give the illusion of great wealth as he set his sights on throwing the biggest bash of all by underwriting DiCaprio’s latest project “The Wolf of Wall Street,” forming a production company with Hilton’s former employee Joey McFarland and Riza Aziz, the stepson of then-Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razar that could cover the hundreds of millions of dollars in expenses. While Low would infer that he was born into wealth without revealing where exactly it was derived from, the attention from shepherding a blockbuster to the screen cast a harsh light on the real provenance of his finances when journalists curious about why a Scorsese movie was being shown in elementary schools as a source of national pride began to uncover ties between Low, Aziz and 1DMB, an economic development fund intended to enrich all of Malaysia over time with investments that instead were funneled into Low’s pockets.

While “The Wolf of Wall Street” now exists as fittingly debaucherous evidence of Low’s exploits, another film “Man on the Run” makes a compelling case for the damage he wrought as he remains a fugitive from justice, with Cassius Michael Kim, a producer of the globetrotting CNN series “The Wonder List with Bill Weir,” criss-crossing the globe to get a handle on how Low not only engineered the con, but how he could hide it for so long with more than a few powerful figures willing to look the other way. Kim talks to the journalists who brought the malfeasance to the public’s attention and the law enforcement that gradually sussed out the various smokescreens that Low operated under, but “Man on the Run” looks high and low within Malaysia itself when speaking to current and former Prime Ministers as well as average citizens on the street to show a sociopolitical situation that was ripe to be taken advantage of when a consolidation of power existed at the top, operating with impunity as the country’s population will be held back from the economic progress that their leaders pledged to make possible.

With “Man on the Run” now making its way into theaters, Kim spoke about how close he came to tracking down Low, creating a cinematic investigation that would properly capture the thrill of the chase and revealing the true cost of his crimes.

The vast scope of it, more than anything and not just the scope of the money stolen, but the way it touches upon so many different aspects of our society that people kind of deify and look up to, whether that’s Hollywood or Wall Street or royalty or the highest reaches of government. It really leaves a little mark on everyone it touches but despite all that, it hasn’t really permeated the consciousness of our society the way I thought it should or would. Even when I started doing the research, there’s so much I didn’t know myself about the deep layers of where all this money went and who helped steal it and launder it and enabled the conspirators. Just the sheer lack of accountability for so many of the people that benefited I thought made it such a juicy story to tackle and also the challenge to cover something that had [previously] been done in print media and then try to put a visual element to it, also helping these people who did so much of the real hard work tell their stories in a streamlined fashion.

You really do unpack a dense story in a really brisk way visually. Was it interesting to enliven this in that way?

Joe Simon, my cinematographer, and I, have collaborated together many times over the last decade and it was a conscious decision we made before we started filming how we wanted to make sure each location had its individual identity and also imparted a different kind of visual language. We knew we’d be switching scenes, but the core of the story would be taking place in Malaysia, which is so different from London, New York, L.A., and DC, so it was really about filming in a cinematic way and with places like New York and London, especially where we’re talking about finance and the movement of money, we tended towards cooler colors and smoother movements, and in Malaysia, we opted to go handheld and really dial in on the vibrancy of not just the colors that were present in the buildings and the people, but just the society. There’s so many times where we’re just in the mix in a way that we weren’t able to be in London and New York and that was the visual contrast that we would offer because the nature of the events also differs from location to location.

There’s also a really canny use of dioramas for such scenes as a meeting between Najib Razak and Mohammed bin Zayed. What was it like to find a way into those moments that you wouldn’t have been able to get into otherwise?

I’ve always just loved miniatures and that aspect of practical filmmaking, and obviously in narrative filmmaking, Miniatures often take the place of real sets, so that was a dynamic that I always wanted to play with and when the opportunity arose for this documentary, I was like, why save that in my quiver? I’m just gonna throw everything at the wall that I’ve always wanted to do. And I was very fortunate to link up with Ian Hunter, this gentleman who won an Academy Award for production design for “Interstellar” and “First Man” and created the miniatures for the first “Total Recall” and when he agreed to work on the project, there were so many places that we were not going to be able to access that play a major role in the story, so we figured what better way than to build a tiny set and use that as a visual representation of these places. And I don’t know if you picked up on this, but a few times we pull back and we reveal that it’s a set and I think it also serves as a visual metaphor for those moments.

I had never been to Malaysia and I’m almost embarrassed to say I didn’t know too much about it. So in addition to researching 1MDB, I felt like I was taking a primer on the history of Malaysia and the nature of Malaysia political systems because I wanted to make sure I knew what I was talking about when I met with these people who were in government. You want to pay respect to who they are by coming on with the knowledge of what they’ve done and what kind of roles and what kind of society they serve in. Having the background in international production helped me know how to navigate that research process and embedding within a new country, and my cinematographer Joe also has been on a lot of these travels with me, so we have a little shorthand for dealing with these situations. But there’s nothing like doing the work. And it’s really about just learning the way Malaysia is structured and how it became a country 65-70 years ago and its history as a new democracy and how that informs the conditions that enable this fraud because that’s what it really ultimately comes down to. You have to know the way the country was built to know why the scandal was allowed to take place.

Was it interesting to enter a situation where there were ongoing criminal cases or political implications to consider? That seemed like a first in your career.

Within a lot of these things we’ve done, there are more present moments. “Stockton on My Mind” was about a mayor who we anticipated being reelected, but was taken down by a shadowy network of misinformation blogs. But then even during “The Wonder List,” we booked an interview with the president of Madagascar to discuss the Timber Mafia and when we did our documentary on the Netherlands, we sat down with Pieter Omtzigt, who’s like the Donald Trump of the Netherlands and was anticipated as being a challenger for the prime minister spot when the election came after our episode aired. So there are moments that prepared me for this. In the course of my career, we’ve sat down with like at least a half dozen different heads of state and having produced those shoots and seeing my colleagues take part in those situations prepared me for this. Now I will say the scope of this story is a little more vast than anything I tackled in the past, but honestly, I look forward to just learning something new and just seeing if I could do it.

You mentioned not necessarily knowing the whole story before digging in. Was there anything that really took you by surprise?

The main thing was there’s a long period of this dialogue that happens before we start filming and through Bill McMurray and Wu Li and all these others, I learned about Chuck O’Neill and Dave Smith as people who were on the ground in Malaysia for the FBI when this all started. They started telling me the details of this covert operation where essentially they’re funneling information from Malaysian informants to the DOJ and FBI once Najib cracks down on the investigations into his shady dealings, and that was something that hadn’t been addressed or talked about in the past, not to any great length, so once I was able to reach Chuck and Dave and then speak to them — and that took many months of earning their trust when they hadn’t talked to anyone else. Through the course of that, you learn so much about the unsung heroes, and one of my regrets is that I wasn’t able to really give full credence to to them because for a variety of reasons, [a lot of them] declined to participate in the film.

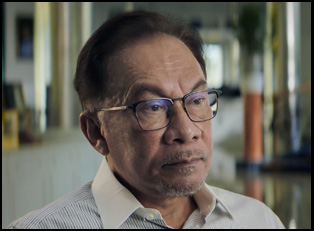

There very much is an atmosphere of fear in Malaysia, and I’m looking forward to going there in a couple of weeks just to see if it’s changed since Anwar Ibrahim became prime minister. But when we were there, it was palpable. Even when we’re talking to the people on the street, you can see from some of their facial expressions [from our interviews] they’re not comfortable talking about these things because they’re afraid of the repercussions. Even people like Abdul Hamid Bador and Abu Kassim, who we name check and who were heads of the police, as well as the Anti-Corruption Commission, who played such a huge role in making sure the American law enforcement was able to bring closures in this case, they still weren’t comfortable coming on camera to speak about the rules. So we had to have Chuck and Dave be proxies for that because I wanted to give a shout out and they were instrumental in this happening. And that was a delicate balance, but those are also things I learned about the bravery of those Malaysians who, despite the dissolving of their checks and balances and institutions, took it upon themselves to make sure that accountability was served.

The film has a more fascinating end title sequence than most when typically you’ll see who declined to participate in the film and you’ll have a good idea why, but when you do get the participation of some surprising figures in the case, there’s more of a curiosity about the reasons why. Was it interesting putting that together?

I think it speaks for itself and I’d hate to hypothesize on what those people’s reasons are. Generally, I think people just wish the story would go away and that’s not just those people [who declined to be interviewed], but that’s people at film festivals or people at distribution platforms who are afraid of offending the people who look bad for their role in this case. And the fact of the matter is, how can you make something go away when so many people are suffering because of it? If any of them spent a day walking around Malaysia, like we did, they would know the true impact of their actions, so I would hope that they would have a little more humility about their roles and whether or not they should speak on it. All those people we list at the end, they had their roles to play, and we gave them the opportunity to speak to us and it would have been a fair and objective platform, but they chose not to take us up on it. So be it.

In that same sequence, it’s alluded to that you at least had a way to get in touch with Jho Low and his attorneys, even if he didn’t respond. Did you actually feel like you got close to reaching him or knowing his whereabouts?

He has a number of attorneys, one of whom we spoke with and one of whom would not return my calls or e-mails. And I have a number of email addresses from Mr. Low, which I’ve e-mailed numerous times in the past, not so recently — although I feel like with everything happening, I should just check in and see how he’s doing. I’ve never gotten a response, but also none of them bounced back, so there are active email addresses, and who knows if he’s the one monitoring them? Rumor has it he’s somewhere in China, in between Shenzhen, Macau, and Hong Kong. I think the accepted story right now is that he’s ferried between safe houses with his family by Chinese intelligence to make sure he’s a moving target [as opposed to] a stationary one. But who knows how long his viability will last for them. He certainly knows where all the bodies are buried, so to speak. But you know there’s a lot of people I think also who probably want him to go away just as well as the story. Hopefully I get a chance to talk to him someday.

It’s been a whirlwind, man. We started out in London and Ireland and it was in a number of theaters in both countries and it was nice to see it on a big screen. In London, the British Malaysian Society sent a nice delegation to watch the film and it was really, really powerful to see their reactions to it. And after the premiere, we had a screening in East London at a different theater for a paying audience and there was actually a very powerful moment where a friend of Kevin Morais, the prosecutor who wrote the arrest warrant for Najib and was murdered, came to the screening and stood up at the end and was very emotional, just thanking us for keeping his story alive. And in the course of researching Kevin Morais, we had hoped to find someone who could speak on his behalf for the film, but he has a complicated family, so we weren’t able to really do that, but we did want to pay tribute to this man who paid the ultimate price. So to meet someone who was his friend and felt so strongly about his story being told was something I felt emotionally impacted by and it was something unexpected as well.

“Man on the Run” is now open in New York at the Village East and opens on September 29th in Los Angeles at the Monica Film Center.